News

An age of choice for development finance: evidence from country case studies

National financing strategies will play a decisive role in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been agreed and the world is gearing up for their implementation. The SDGs are ambitious, and their achievement will require financing that is not only massive in scale, but effective in delivering impacts at the country level.

Governments pursuing the SDGs find themselves in ‘age of choice’ for development finance, with new financing instruments and providers to choose from – far beyond the traditional donors – to support their development priorities.

This age of choice could not be more timely, as the comprehensive and universal SDGs demand a multitude of financing tools and partnerships. It also means, however, that developing countries need a far better understanding of the different financing options and partners available to them. At the same time, donors that want to be chosen as partners must work harder to give developing countries what they actually need if the finance they offer is to have a real impact on national priorities.

This report examines the viewpoints of developing country governments on this new age of choice in general, and on non-traditional sources of development finance in particular. It looks at the ‘beyond ODA flows’ (BOFs) that developing countries can select, explores their choices and the factors that shape them.

The findings in this report are based on nine country case studies that were carried out in stable lower-income countries (Ethiopia, Uganda, Ghana, Senegal, Kenya, Zambia) and lower-middle-income countries (Cambodia, Viet Nam and Lao PDR) from 2012 to 2015, drawing on interviews with government officials, development partners and civil society organisations.

BOFs are not part of traditional official development assistance (ODA), but they are sources of external finance that could be available to governments to fund national development strategies. They include:

A new age of choice for developing countries

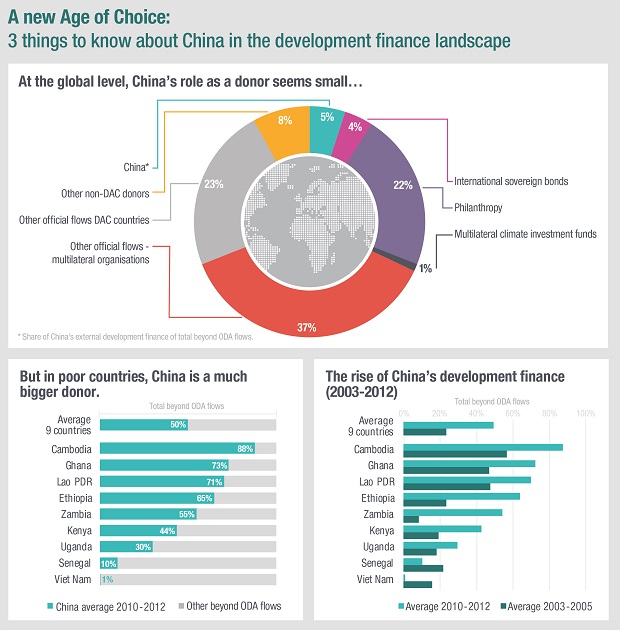

Developing countries now have more external finance available to them to fund national development than ever before. Total external development finance to all developing countries more than doubled between 2003 and 2012 to $269 billion, with BOFs accounting for $120 billion, or around 45%. In 2012, the bulk of this $120 billion came from OOFs (37%) and bilateral DAC donors (23%), followed by philanthropic assistance (22%) and emerging donors (13%), marked by a growing share from China. Other sources were international sovereign bonds (4%) and multilateral climate finance (1%).

More choice means more potential bargaining power for national governments

The emergence of new development finance providers has strengthened the negotiating power of some developing countries with traditional donors. This seemed to be the case for Cambodia, Ethiopia and Uganda, where China’s presence as a donor stood out.

The Government of Cambodia, for example, cancelled the 2012 Cambodia Development Cooperation Forum to review progress against conditionalities – a cancellation some interviewees blamed on disputes with the World Bank. In Ethiopia, some interviewees said that the emergence of new donors has allowed the government to adopt policies that do not tally with the conventional policy conditions set by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. Similarly, interviewees in Uganda believed that the growing influence of China has allowed the Government to pay less attention to the governance concerns of traditional donors.

A landscape dominated by ODA, China and sovereign bonds

Development finance from traditional donors still matters, and is growing

ODA remains the largest single source of external development finance at country level and its flows are growing, even in middle-income countries (MICs). Its volume increased in all case study countries except Zambia. Kenya and Viet Nam have seen five-fold and three-fold increases of ODA respectively in the last ten years. In Cambodia, Ethiopia, Lao PDR, Senegal and Uganda, the volume of ODA doubled between 2003 and 2012.

China is the largest non-traditional donor at country level

China accounted for half of all BOFs from 2010 to 2012 across the case study countries, and for more than 70% in Cambodia, Ghana, and Lao PDR. The average financial contribution from China surpasses that of any other emerging donors (like Brazil, India and South Africa).

This doesn’t mean, however, that every government can count on massive amounts of finance from China. Much seems to depend on geopolitical factors, as countries recovering from or embroiled in tense diplomatic relationships with China (such as Senegal and Viet Nam) receive less of its official finance.

International sovereign bonds are the second largest source of non-traditional flows

Every case study country except Cambodia and Uganda (both LICs) has accessed international capital markets over the past decade, particularly to fund their investment in infrastructure.

The volume of philanthropic assistance and climate finance is very small

Philanthropic assistance may be the second largest source of external BOFs at the global level, but its volume at country level is minimal; amounting to the equivalent of just 1% of ODA flows in both Ghana and Senegal between 2003 and 2012. This is because philanthropic organisations rarely deal directly with governments – instead, they channel their funds via trust funds and international organisations.

The volume of climate finance funds is also extremely small at country level, even in the countries most vulnerable to climate change. Senegal, for example, ranks high (number 137 of 180 countries) on the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index, but total climate finance pledged to the country since 2003 amounts to only $32 million, and only 60% of this had been disbursed by 2013. This stands in stark contrast to the more than $1 billion of ODA Senegal received in 2011 alone.

What shapes the choices made on development finance?

Developing country priorities: volume, speed, ownership, alignment and diversification

The top priorities for developing countries remain largely in line with the principles of aid effectiveness, regardless of the changing finance landscape. Some countries stressed speed of disbursement, while many prioritized their ownership of development programmes that are aligned with national development strategies, consistent with the principles of the Paris Declaration. Several, including Kenya, Lao PDR and Cambodia, emphasised the sheer volume of finance, as they need to invest heavily in infrastructure projects. They have issued international sovereign bonds over the past 10 years to diversify their funding portfolio because they require amounts that other enders, especially multilateral developmet banks (MDBs) and bilateral DAC donors, have not been able to provide.

A general trend across the case study countries was the increasing issuance of sovereign bonds even though their terms and conditions are not as favourable as loans from bilateral and multilateral lenders. Governments issue bonds because it allows them to re-finance previous obligations and sends a clear signal: this country can access international financial markets. Developing countries also valued the absence of the policy conditionality and delays that often characterise the disbursement of traditional development finance.

Non-traditional donors have little interest in aid coordination mechanisms

It seems that the energy around the aid effectiveness agenda is faltering, given the lack of interest among developing country governments and emerging donors, even in countries that were very active in the processes around the Paris Declaration, the Accra Agenda for Action and the Busan High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness. Emerging donors take no active part in aid coordination mechanisms in the case study countries, with the exception of Zambia. They are either entirely absent from such processes or only participate as observers. Most negotiations with developing country governments are bilateral and often involve discussions with contractors (especially those from China) at a very early stage in the project implementation process.

Public debt is on the rise

Public debt levels have soared over the past decade in Kenya, Lao PDR, Uganda and Viet Nam. With the exception of Lao PDR, these countries have debt-to-GDP ceilings, set by parliament or regional organisations, which they will reach very soon. This could make it difficult for them to take on more loan financing to meet national development priorities. Loan financing is essential, as the SDGs cannot be achieved through grant financing alone.

Managing a new age of choice – a way forward

The range of recommendations offered by this report can be condensed into 10 recommendations to help developing countries and donors navigate their way through a transformed development finance landscape.

Developing country governments can take five main steps to capitalise on the new age of choice:

-

Know what you want. Countries with clear national development strategies, such as Ethiopia and Uganda, were more confident when dealing with potential donors. Governments should put together national development strategies that identifiy priority sectors and how funds should be spent. The clear message is: seek a range of funding that supports your development strategy, reject any funding that does not, and agree clear priorities for the ‘terms and conditions’ of the development finance flows you choose.

-

Know how much finance is coming in, and keep track of where it goes. The case study countries often lack data monitoring on development finance by Ministries of Finance and Planning. Ministries should, therefore, improve their efforts to build and maintain good data sets so they can see how much finance is coming in, what kind of finance it is, where it is from, and where it is going. This would allow governments to see the links between financial flows and tangible progress. At the global level, a data revolution is needed to support achievement of the SDGs. At local level, a data revolution is needed for good strategic planning and better evaluation.

-

Think outside the ODA box. Most financing strategies in the case study countries still focus on ODA but, in the new age of choice, alternative sources of finance generated $120 billion for developing countries in 2012 alone. While ODA still matters, access to it will decline as economies grow. So include public and private non-concessional financing in your national development strategies. This will help you achieve a range of development objectives in the face of rising debt levels and limits on the amount of traditional financing you can access.

-

Play the field. Don’t just stick to traditional donors. China and the international sovereign bond markets are already major sources of development finance at country level, and philanthropists and other non-DAC donors at the global level. Negotiate with both new and old development finance providers and be strategic in managing your relationships with them. Recognising the distinctive characteristics of a provider will increase your chances of a successful negotiation.

-

Don’t forget about macroeconomic performance. This might seem obvious, but successful sovereign bond issuances rely on good macroeconomic indicators and their forecasts. Poor macroeconomic performance means lower credit ratings and higher interest rates for future issuances, making the refinancing of international sovereign bonds unsustainable.

Donors can take five main steps to provide more effective development finance:

-

Remember that ODA still matters. It is still by far the largest source of external development finance available to governments in developing countries. While debates on ‘beyond ODA’ are important, donors must ensure that ODA itself is effective in supporting national development plans and progress towards the SDGs.

-

Support countries’ own strategies and policies, and do it quickly. Evidence suggests that developing countries are using the availability of new financing options to their advantage, and that this has bolstered their negotiating position with donors. Traditional donors need to give developing country governments what they want – ownership, alignment and swift disbursements – or risk losing ground to other providers and, ultimately, losing relevance.

-

New donors need to respond to developing country priorities. The biggest new donor – China – on average accounts for more than 50% of ‘beyond ODA flows’ across all case study countries, and for more than 70% in three of them. All providers, including China, need to ensure that their finance contributes effectively to the achievement of the SDGs, is ‘owned’ by the country that receives it, is aligned to that country’s priorities, and promotes macroeconomic and debt sustainability.

-

Find out what is going on with the very small flows of philanthropic and climate finance. It may be that philanthropic finance is subsumed into flows from NGOs and global funds, but better tracking is needed. Given the recent landmark agreements on climate change, it is alarming that so little climate finance goes to countries that are vulnerable to climate change.

-

Don’t forget about debt management. Debt levels have risen rapidly in many countries, and those with debt ceilings are about to hit them. Given the vast financing needs for the SDG agenda, donors and aid-recipient governments must work together to identify funding options that do not heighten the risk of debt distress. This also requires multilateral development banks to reflect on whether limited supply and terms and conditions are pushing developing countries towards more expensive – and perhaps more risky – capital markets.

Downloads

- An age of choice for development finance: evidence from country case studies | Executive Summary

- An age of choice for development finance evidence from country case studies | Synthesis Report

- Age of choice: Kenya in the new development finance landscape | April 2016

- Age of choice: Uganda in the new development finance landscape | April 2016