News

How can African countries boost their participation in the services aspects of GVCs?

This article considers the various factors that drive competitiveness in services, a critical but often overlooked part of global value chains. In value-added terms, services now account for nearly half of world trade, yet too few African developing countries are taking advantage of the new opportunities available.

Services are a critical but often overlooked part of the growing global value chain (GVC) phenomenon. Today, the production of goods and services involves a combination of intermediate inputs and service activities, sourced globally, to make up a finished output for the final consumer. It is this fragmentation of production that has led to the creation of global value chains (GVCs).

Services play a key role in the operation of value chains by providing the “glue” that connects each point of the production process. For many African states, participation in the services sector is particularly important since this sector is less capital intensive than manufacturing, thus allowing for potentially greater participation in global markets and offering an alternative route to economic development other than that of the traditional agriculture and manufacturing paths.

In value added terms, services now account for nearly half of world trade with developing countries’ share in world services exports experiencing a nearly 20 percent increase in the last twenty years (OECD/WTO TiVA database). Despite this recent increase, too few developing countries are taking advantage of the new opportunities to specialise in the export of services ‘tasks’, that go into global value chains, both regionally and around the world.

Development potential of GVCs for Africa

In a world of GVCs, developing economies, including the least developed, have increased opportunities to enter into intermediate activities by adding relatively small amounts of value-added to any particular product. GVCs therefore open up tremendous opportunities for development that did not previously exist in the world economy. Rather than having to be competitive in all aspects of the production of a good or service, developing countries can now capture a single component or task going into a value chain. All tasks along the supply chain are being increasingly outsourced and offshored wherever they can be most efficiently performed. Thus international trade is made up predominantly at present by intermediate goods and services.

What remains much less understood is the fact that value chains including GVCs, exist not only in the goods but also in the services sector itself. In a services value chain, any cluster of activities can become a core competence or be outsourced from the services firm. It is increasingly recognised that for many elaborately transformed manufactures (such as the Iphone) the highest value added is contributed by services inputs, often at the R&D and design phase or at the logistic/distribution phase. Services inputs therefore represent new competitive opportunities for specialisation and for the participation of emerging suppliers.

One of the main development implications for developing economies of the new possibilities offered by services and GVCs is that it is possible for governments to ‘create’ a comparative advantage in a service task. Since services are all about people and human capital rather than physical capital, the role of policy can be determinant in this regard. Because of the possibility of capturing only one type of services activity, even small economies may position themselves in niche markets.

For those countries on the lower income rankings, services may provide a platform for ‘leap-frogging’ stages of development if the government can help to create conditions necessary for developing the services sector, allowing countries to bypass the manufacturing stage and move directly into services, including in international markets.

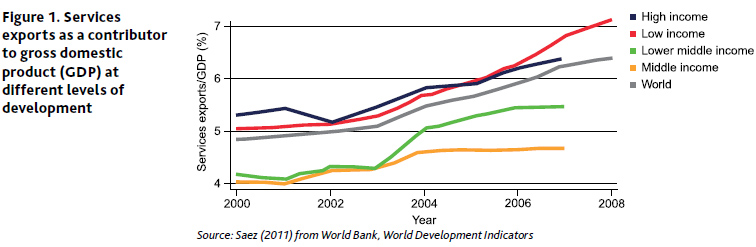

As shown in Figure 1 below, services exports are making greater contributions to GDP for poorer countries than for middle-income economies: just below 6 per cent for lower middle income economies and just over 6 per cent for low-income economies. Finding a way to ‘fit’ into a GVC through taking on an outsourced services task is one of the ways that developing countries can target an alternative development route.

African countries’ participation in services exports and GVCs

Many African countries are already exporting services, some without being aware of it; in turn some of these services are destined for use in GVCs. The following case studies from Africa give us information as to what types of services are already being exported:

Education services: Ghana

Ghana has concentrated recent efforts in the development of exports in the educational sector; this has resulted in Ghana becoming the leading destination for learning English for francophone West African countries. Ghana is exporting educational services in the form of admissions of foreign students into Ghanaian colleges and universities.

Professional services: Kenya

Kenya, the country with the most advanced human resource base in the East African Community (EAC) region, has a large and well developed services sector with professional service providers in many areas ranging from banking and insurance to legal services, accounting, ICT and engineering. Over the past few years Kenya has targeted export of professional services to other EAC states, riding on increased demand for these services in a region of 127 million people and a combined GDP of US$73 billion (World Bank and Kenya’s Export Promotion Council).

ICT and IT services: Uganda and South Africa

Uganda is one of Africa’s better performers in the export of Information and communications technology (ICT)-related services, which are reported to have grown from US$0.7 million in 2003-04 to US$31.5 million in 2006-07, a 45-fold increase. This makes the ICT sector one of Uganda’s best export growth performers (UNCTAD, 2011).

According to a World Bank study (Dihel et al. 2012: 262), South Africa’s BPO sector is forecast to grow to 1.9 billion USD by 2015. South Africa has the potential to compete with some of the strongest global exporters of BPO, having already attracted some of the world’s top investors in the sector. The World Bank study notes that among the key factors influencing South Africa’s success was the crafting of deliberate policies and strategies to help create an enabling business environment and cut telecommunications costs.

Factors relevant to services competitiveness

The opportunities offered by the new pattern of world trade in the form of value chains make it imperative that economies give greater attention to efficient logistics as well as their services competitiveness, which will determine their ability to attract services tasks onshore for production to the global market.

Inefficient domestic logistics, as well as other domestic services inefficiencies, will reduce the likelihood of success in efforts to participate in global goods value chains. Many services rely on underlying infrastructure and thus local inefficiencies in the latter are prejudicing opportunities for African countries to participate in global value chains.

Competitiveness in services can be greatly enhanced by the actions of individual countries, driven by policy choices and efforts made to create an environment that will enable and encourage trade. Because so many of the constraints to services trade are behind-the-border measures, the efficiency of domestic regulatory regimes is also highly relevant to participation in services trade. Drivers of competitiveness, summarised in a framework by the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Business Advisory Council, include: endowments, especially human capital, investment in intangible assets (corporate intellectual property, enabling digital infrastructure, quality of institutions, efficiency of domestic regulation, connectedness with the international market, services business stakeholder consultation, and mainstreaming services policy as a priority focus into the national development planning process.

Policy recommendations

True interconnectedness will only be possible when the current lack of understanding of the services sector is addressed. Currently there is limited public awareness of the economic significance of services for economic development and relatively little advocacy to raise that awareness. Identifying and addressing the specific services choke points in GVCs that are impacting negatively on African country participation in value chains ultimately requires that fundamental framework issues such as the lack of focused policy planning tools, overly burdensome domestic regulatory regimes, and insufficient intergovernmental agency co-ordination, be addressed.

In order to boost the participation of African countries in the services aspects of GVC further background research should be conducted, particularly through case studies, in order to inform an active policy and regulatory dialogue. Also, technical assistance and capacity building in support of African nations should focus on improving the evidence base, raising awareness and disseminating research results. African governments should be directing policy attention to achieving efficiency gains in logistics services such as improved transportation, telecommunication and distribution infrastructure so as to facilitate cross-border trade in both goods and services. Regulatory regimes should also be examined for their appropriateness and strengthened where necessary.

International capacity building efforts should be directed to identifying and leveraging the factors that impact on services competitiveness overall as well as in individual prospective services growth sectors in tandem with trade policy reform. Lastly, African donor countries should partner with trade-related international organisations to showcase best practice methods and tools for services export promotion.

Sherry Stephenson is a Senior Fellow at the ICTSD and Jane Drake Brockman is Senior Services Adviser at the ITC, Geneva.

This article is published under Bridges Africa, Volume 4 - Number 1 by the International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development.

It is based on the following report: ‘The Services Trade Dimension of Global Value Chain: Policy Implications for Commonwealth Developing Countries and Small States’, The Commonwealth Secretariat, December 2014.