News

Customized trade remedies in Africa – the case of the COMESA-EAC-SADC Tripartite Free Trade Area

Meaning of trade remedies

Trade remedies have been variously defined, for instance:

“The term trade remedy measures or, simply trade remedies, generally refers to three types of import restrictions authorized under national and international trade laws: antidumping duties, countervailing duties, and safeguards” (Zheng, 2012);

“Trade remedies – or trade defence – are contingent measures enacted to defend local producers in certain circumstances. They take three principal forms: anti-dumping measures, countervailing measures and safeguard measures (Illy, 2012); and

“The term ‘trade remedy laws’ refers to three types of national laws that impose import restrictions under specified circumstances. ‘Safeguard measures’ are temporary trade restrictions, typically tariffs or quotas, which are imposed in response to import surges that injure or threaten ‘serious injury’ to a competing industry in an importing nation. ‘Antidumping duties’ are tariffs in addition to ordinary customs duties that are imposed to counteract certain unfair practices by private firms that injure or threaten to cause ‘material injury’ to a competing industry in an importing nation. ‘Countervailing duties’ are tariffs in addition to ordinary customs duties that are imposed to counteract certain subsidies bestowed on exporters by their governments, when they cause or threaten to cause material injury to a competing industry” (Sykes, 2005).

These are not legal definitions as such, and leave out lots of details, the possibility of price undertakings for instance as one form the measures can take as well as the detailed conditions and parameters; but they can greatly assist to provide a glimpse of the territory. The WTO Agreements contain the comprehensive definitions, as well as the substantive and procedural rules that govern these measures.

Brief history of trade remedies

A practical issue governments usually address in entering trade agreements is the protection of domestic industries against unfair trade practices or significant injury by competition from imported products.

The world’s first modern anti-dumping law was enacted by Canada in 1904, against American steel makers, on the following ground as articulated by the then Finance Minister:

We find today that the high tariff countries have adopted that method of trade which has now come to be known as slaughtering, or perhaps the word more frequently used is dumping; that is to say, that the trust or combine, having obtained command and control of its own market and finding that it will have a surplus of goods, sets out to obtain command of a neighbouring market, and for the purpose of obtaining a neighbouring market will put aside all reasonable considerations with regard to the cost or fair price of the goods; the only principle recognized is that the goods must be sold and the market obtained…. This dumping then, is an evil and we propose to deal with it. (Illy, 2020)

The emotive politics of antidumping measures, as well as the interface with anti-competitive practices, has remained with us over the years. Other countries followed suit; New Zealand (1905), Australia (1906), South Africa (1914), the US (1916) and UK (1921). When the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was provisionally adopted in 1947, its Article VI contained provisions condemning dumping.

Subsidies countervailing measures also have a long history, also going back to Adam Smith’s insightful discourses in 1776 on state bounties for exports and on mercantilism, and to the 1791 Hamilton Report which explained that unofficial bounties could harm US efforts to build its national industries. The first modern countervailing law was the US Tariff Act of 1897.

Safeguards, on the other hand, came later; the first safeguard law being the US Reciprocal Trade Agreements Program of the Trade Act of 1934. Earlier trade agreements didn’t have safeguard clauses, or “safety valves” or “escape clauses” as they came to be known, and were either terminated or breached in times of crisis resulting from import surges. The US-Mexico Reciprocal Trade Agreement of 1942 had a safeguard clause in its modern form. The GATT 1947 provided for the emergency safeguard as it came to be called.

The GATT 1947 has been renegotiated in a number of rounds, and its latest modification or improvement is GATT 1994 now including three detailed agreements on antidumping, subsidies countervailing and safeguard measures; as part of the WTO Agreement which entered force on 1 January 1995. Negotiations are again underway, and yet to be completed since 2001, under the Doha Development Agenda, to improve the disciplines on dumping and countervailing measures while taking into account the concerns of developing countries; because the practice over the years has shown shortcomings to be addressed.

This background makes the point that trade remedies have been a practice in international trade agreements and in national laws for a long time now; that starting with national laws and bilateral trade agreements, trade remedies were incorporated into the GATT when it was provisionally concluded in 1947 and maintained as the GATT has grown over the years into the multilateral regime on trade in goods covering a total of 164 countries of the world, including 21 of the 26 tripartite member/partner states[1], and that efforts at improvement remain ongoing.

Key issues in considering trade remedies

What then have been the core issues in the discussion on trade remedies? Among others, the core issues have been the following:

What useful purpose do trade remedies serve?

Are trade remedies in their current form as set out in the WTO Agreements appropriate for achieving the intended objectives?

How can abuse of trade remedies best be prevented?

From a reading of the international rules, are trade remedies required, prohibited, or optional in free trade areas?

What flexibility exists for trade remedies in FTAs?

How can developing countries improve their capacity to use trade remedies?

In addressing these issues, the overarching position taken in this article is that trade remedies can serve a useful purpose in terms of encouraging countries to agree to ambitious levels of liberalization in RTAs, but every care should be taken to avoid abuse and to limit use to only the deserving cases. This position is backed by the policy and the relevant WTO rules, and by the overall flow of scholarship on the matter, as this paper tries to show. For the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA), if trade remedies are to be included, they should be flexible and simple to use, as indeed the negotiators (TTNF) instructed in the Terms of Reference establishing the Technical Working Group (TWG) on Trade Remedies and Dispute Settlement. In addition, there should be concerted efforts by governments and partners to build the capacity of stakeholders especially the private sector and civil society including consumer organisations, as well as of all relevant line ministries that work to promote the public interest. Furthermore, to deal with the monopolistic abuses resulting from trade remedies, national and regional competition policy and law should complement market regulation interventions to ensure fair trading, to ensure efficient markets that support job and wealth creation especially among small economic operators, and to protect society at large.

The case for and the case against trade remedies

Regarding the purpose of trade remedies, opponents argue that trade remedies are protectionist tools that benefit some producers or even monopolists while hurting consumers, importers and manufacturers that need cheap inputs; and on the whole constitute bad economic policy by reducing welfare and maintaining inefficient producers through sheer tariff and quota protectionism. Trade remedies therefore serve no useful purpose and should be eliminated from international trade agreements in order to promote efficiency in resource allocation, to promote competition and functioning markets. Some in this group (Sykes, 2005) argue that the place of antidumping and countervailing measures can then be taken up by competition rules to deal with unfair trade practices and by direct challenges under WTO rules on prohibited or actionable subsidies against member states that subsidize exports.

On the other hand, supporters argue that trade remedies provide governments the confidence to agree to trade liberalization, in the knowledge that contingent measures exist to remedy situations which can arise in future where domestic industries would otherwise suffer material or serious injury or threat of it: “contingent protection measures can be seen as strategic tools for governments to reduce the political cost and internal domestic pressure involved in opening domestic markets to international trade” (Denner, 2009). Supporters argue that dumping in particular may make good business sense in that sales abroad can still be profitable when sold below the price in the market of the exporting market, without the intention of killing the competition and then raising the prices (predatory dumping); that a response to a government that subsidizes its exports to make them cheap in the importing market should be a “thank you note” to the embassy of the exporting country; and that the escape clause in terms of possible safeguard measures against import surges can only be prudent, because the clause assists to prevent breach or termination of trade agreements which would be the only resort where there is no provision for safeguard measures. Supporters therefore argue that trade remedies are indispensable (Denner, 2009).

There is a middle ground as well, arguing that trade remedies are bad economic policy but should be maintained for reasons of pragmatism or political expediency; political leaders do not have the will or the wherewithal not to have trade remedies in the agreements they conclude – they would lose office if they didn’t negotiate for or support the application of trade remedies. This school of thought then focuses on how to make the best of trade remedies through improvements to prevent abuse (Zheng, 2012).

An illustrative example of recommendations proffered by scholars is the following:

Eventually, WTO Members could instead respond to predatory dumping with competition laws, to illegal subsidies with WTO dispute settlement, and to import surges with safeguards pursuant to a reformed safeguard regime. In the shorter term, WTO provisions do not prevent RTA partners from eliminating trade remedies among themselves (Voon, 2010, p.3).

Some of the scholars provide case studies or examples of reasons for improvement. Gomez, for instance, studied how the importation of stranded wire, rope and cables of iron steel originating from the UK was thwarted by an antidumping duty the International Trade Administration Commission (ITAC) of South Africa investigated and recommended imposition of, though the investigation had shown that only fishing rope was being dumped. The investigation was instigated by SCAW South Africa (Pty), a South African producer of these products and a competitor of the British company (Bridon International Ltd), which was exporting the products to South Africa. When ITAC subsequently recommended the lifting of antidumping measures, after a finding that the injury or threat no longer existed, SCAW brought a case in the South African courts to prevent the lifting of the duties. Gomez, recommended that South Africa could consider vigorously applying its robust competition laws to such cases (Gomez, 2010).

The various views notwithstanding, there has been a large number of national investigations to apply trade remedies by WTO Members: a total of 4,230 initiations of antidumping investigations from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2012, and 302 subsidies countervailing investigations over the same period; and 255 safeguard investigations from 29 March 1995 to 31 March 2013 (WTO, 2012). But not surprisingly, given the controversy, there has been a large number of disputes heard and decided by the WTO Appellate Body and panels, relating to trade remedies: 98 disputes on subsidies countervailing measures, 96 on antidumping measures, and 43 on safeguard measures (WTO, 2012). Many of the trade remedy measures were found inconsistent with the WTO rules.

The history of trade remedies, the use, and the interpretation put to them by the WTO Appellate Body and the panels show that the trade remedies serve a purpose in multilateral trade liberalization in the context of GATT. The controversy however, as well as the large number of cases at the WTO, show also that trade remedies can be abused and that it is quite a complicated task to apply the rules correctly, more so for member states with capacity constraints. This is why this paper recommends that the TFTA should have trade remedies, but they should be modified or improved to prevent abuse and to suit the conditions of the tripartite member/partner states.

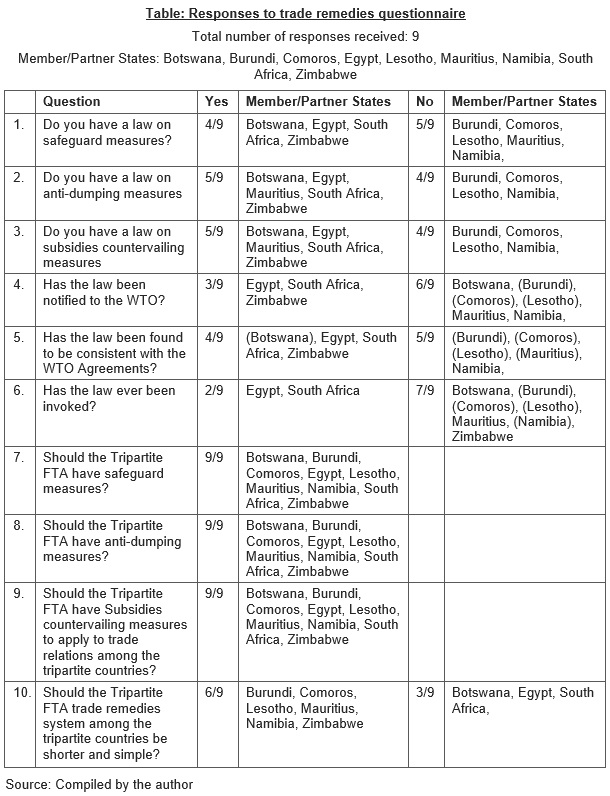

The Tripartite Task Force (secretariat) sent out a questionnaire to member/partner states seeking responses on a number of issues. A total of nine responses were received, namely, from Botswana, Burundi, Comoros, Egypt, Lesotho, Mauritius, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe. The Table below is a compilation of the responses. On the question of whether the Tripartite FTA should have trade remedies, all nine member states responded in the affirmative.

On the question of whether the Tripartite trade remedies should be shorter and simpler, six out of the nine member/partner states responded in the affirmative, namely, Burundi, Comoros, Lesotho, Mauritius, Namibia, and Zimbabwe (though Mauritius preferred to say the trade remedies should be simpler and easy to implement). Three member states responded that they preferred to use the WTO instruments, namely, Botswana, Egypt and South Africa, giving the reason that they needed to respect their WTO obligations.

Member/partner states with trade remedy laws and institutions

Antidumping laws

According to their notifications to the WTO, the following eight tripartite member/partner states have antidumping laws: Egypt, Kenya, Malawi, Mauritius, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The remaining 18 tripartite member/partner states do not have antidumping laws in place.

Subsidies countervailing laws

Ten tripartite member/partner states have made notifications to the WTO under the Subsidies Agreement. Of these, Burundi, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia and Zimbabwe have notified that they don’t have subsidies countervailing laws; Swaziland, Uganda and Zambia that they don’t give any subsidies; Mauritius, Namibia and South Africa that they maintain some notifiable subsidies; and Uganda and Zambia that they have laws for taking subsidies countervailing measures.

Safeguard laws

Only three member states, that is, Egypt, South Africa and Zambia have laws for taking safeguard measures as notified to the WTO.

Questionnaire on trade remedies

A questionnaire was administered to government officials from the countries negotiating the Tripartite FTA. On whether the member/partner state has the law for taking safeguard, antidumping, and subsidies countervailing measures, five member/partner states confirmed that they have the law, namely, Botswana, Egypt, Mauritius, South Africa, and Zimbabwe; while Burundi, Comoros, Lesotho and Namibia said they didn’t. However, Mauritius said it didn’t have a safeguard measures law, and Burundi explained that it can use the EAC trade remedy regulations. Botswana said it has recently enacted a law for taking these measures, in July 2013, but the President is yet to assent to it; the law will enter into force when assented to by the President. Then it will be notified to the WTO.

Trade remedy institutions

Only Egypt and South Africa have functioning regulatory and institutional frameworks, that is, investigating authorities. In response to the questionnaire, Zimbabwe indicated that it has a dedicated institution for undertaking investigations for trade remedies. Additional information received is that Mauritius has considered using private investigators, such as retired civil servants.

Assessment of the prevalence of trade remedy laws and institutions in the tripartite

It would then seem a fair assessment that trade remedy laws and institutions are scarce in the tripartite region. Noting that the WTO Agreements require the existence of WTO-compliant and notified national laws and institutions as a pre-requisite for taking trade remedy measures under those Agreements, it can also be a fair assessment that tripartite member/partner states on the whole lack the legal and institutional capacity at the moment to invoke and impose trade remedy measures under the WTO Agreements. In this vein, the next section looks at the actual utilization of WTO trade remedy agreements.

It may be noteworthy that Uganda’s notification to the WTO, referred to and notified the COMESA Treaty provisions on trade remedies, being the only country that has done this. But it can be pointed out in passing that subsequently, the Uganda Law Reform Commission has had a Draft Bill for a detailed WTO-consistent law and regulations for about 10 years, without much success in it being passed by the Parliament into law. Kenya and Mauritius also continue their efforts to have trade remedy laws; while Zambia and Zimbabwe have what Ousseni Illy termed “partial” trade remedy laws (Illy, 2012, p.42), meaning incomplete. It would appear that parliamentary processes, including lack of prioritization for placement on the agenda in light of other pressing national priorities or due to a backlog or due to low familiarity with the subject, can also pause challenges to adoption and use of trade remedy laws.

Empirical facts on utilisation of WTO trade remedy measures

Between 1 January 1995 and 31 December 2012[2], WTO Members initiated a total of 4,230 antidumping investigations. Of this total, South Africa initiated 217 investigations, while Egypt did 71, these being the only two tripartite member states that have ever undertaken antidumping investigations and notified them to the WTO since the establishment of the WTO in 1995.

Over the same period, WTO Member initiated 302 subsidies countervailing investigations. Again, only South Africa and Egypt participated, with 13 and 4 initiations respectively.

Regarding safeguard measures, of a total of 255 investigations over the period of 1995 to 2013, Egypt initiated 9 and South Africa 3 respectively.

These figures show quite clearly that utilization of trade remedy measures by the tripartite member/partner states has been minimal, with only Egypt and South Africa as users; even these two are relatively minimal users compared to the other WTO members. In contrast, the most avid users have been the developed countries and the advanced developing countries. For instance, over the 1995-2012 period, India did 677, US 469, Argentina 303, Brazil 279 and Australia 247 antidumping investigations. The US did 119 safeguard countervailing investigations out of the total of 302. India initiated 69 safeguard investigations out of the total of 255 over the period.

Responses to the questionnaire on trade remedies are also to the effect that, among the nine member/partner states that responded, only Egypt and South Africa have invoked the trade remedy measures under their national laws.

The RECs’ regimes on trade remedies

The COMESA, EAC and SADC have provisions in their respective instruments on antidumping, subsidies countervailing and safeguard measures.

Availability of trade remedy provisions – primary sources

Regarding availability of trade remedy provisions and general structure, the primary sources, that is, the REC instruments, show that:

The main treaties or protocols contain provisions on trade remedies in broad terms;

These provisions are then supplemented in two ways: either by providing that member/partner states can use the relevant applicable WTO Agreements, namely, the Agreement on Antidumping, Countervailing, or Safeguard Measures, in the case of SADC; or through setting out detailed substantive and procedural provisions that are WTO-consistent, in Regulations in the case of COMESA or in an Annex and Regulations in the case of the EAC;

The COMESA and EAC instruments create dedicated regional sub-committees on trade remedies to oversee the implementation of the provisions; but the instruments do not create regional investigating authorities; and

If an example be given of a cooperative investigating authority: under the International Trade Administration Act of South Africa of 2003, the Government established the International Trade Administration Commission (ITAC) also in 2003, in accordance with the requirement under the SACU Treaty of 2002 that member states should have national laws and institutions on trade remedies; ITAC now serves as the investigating authority for the other SACU member states as well, namely, Botswana, Namibia, Lesotho and Swaziland as members of the customs union. SACU investigations are supposed to use detailed WTO-consistent rules (Joubert, 2012).

Regarding the content of the trade remedy provisions of the RECs, it can be noted that the provisions define trade remedies and set out the substantive requirements in the usual standard or conventional terms as in the WTO Agreements, except that Article 61 of the COMESA Treaty provides for a safeguard measure against “serious disturbances occurring in the economy of a member state following the application of the provisions of this chapter”, rather than “serious injury or threat of serious injury” as the WTO Safeguards Agreement says. However, it should be added that the detailed COMESA Regulations on Trade Remedies faithfully clone the WTO Agreements, which it should not be forgotten have not been used yet in the region especially with respect to antidumping and subsidy countervailing measures.

Definitional and substantive requirements

A comparison and contrast of the requirements under the WTO trade remedy rules shows that there are substantial similarities across the three WTO Agreements.

The Appellate Body has noted the similarities:

We note that Article 11.3 is textually identical to Article 21.3 of the SCM Agreement, except that, in Article 21.3, the word “countervailing” is used in place of the word “anti-dumping” and the word “subsidization” is used in place of the word “dumping”. Given the parallel wording of these two articles, we believe that the explanation, in our Report in US – Carbon Steel, of the nature of the sunset review provision in the SCM Agreement also serves, mutatis mutandis, as an apt description of Article 11.3 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement.

The similarities may make a case for having one instrument covering the three remedies, or at least close coordination among the various trade remedies. Considerable similarities exist especially with respect to the procedural requirements for notifications, thorough investigations, and the idea of provisional measures and eventually final measures that are nevertheless subject to possible judicial review, and have to eventually be terminated since they are by nature temporary measures.

For antidumping measures, the main definitional and substantive requirements are as follows:

Dumping occurs when an enterprise sells a product in an importing market at a price below the market value in the market of the country from which the product is exported, with a direct result of causing material injury or threatening material injury to industries producing like or directly competitive products;

The market value can be established using, the price when the product is sold in the export market or in a third market, or using the constructed value, that is, constructed from the production cost and reasonable mark-ups;

The antidumping measures take the form of duties not higher than the margin of dumping or price undertakings to raise the price in order to remove the dumping;

The measures are taken in respect of the particular dumped imported product; and

There are detailed requirements on parameters, duration and reviews, among others.

For subsidies, there are two main approaches. A WTO Member can directly take another to the WTO Dispute Settlement Mechanism to challenge its prohibited or actionable subsidies under the Subsidies Agreement. The second approach is to take subsidies countervailing measures against the subsidized imports if they cause or threaten to cause material injury to a domestic industry producing like or directly competitive products. The countervailing measures, in the form of higher duties or price undertakings, must not be more than necessary to offset the subsidy. There are detailed provisions on parameters, duration and reviews.

For safeguards, there should be an unforeseen surge in imports that causes or threatens to cause serious injury to a domestic industry producing like or directly competitive products. Reports from the WTO Appellate Body and Panels show that it has proved very difficult for safeguard investigations and measures to have complied with the WTO Safeguards Agreement.

One major difference not to be lost sight of is that the injury or threat for taking antidumping and subsidies countervailing measures must be “material”, while the injury or threat for taking safeguard measures must be “serious”. The difference between these two is that “serious” injury is a higher standard than “material” injury. Other differences include the duration of provisional measures and the final measures, the nature of the remedies (instead of higher duties, safeguards may take the form of quotas), provisions for special and differential treatment for developing countries (a threshold of at least 3% of total imports of the product for safeguard measures to be taken by developed countries against a developing country), constructive remedies should be explored for antidumping measures against developing countries, and so on. These differences should be borne in mind in producing a consolidated law or agreement on trade remedies, as indeed has been done in the EAC and COMESA consolidated regulations on trade remedies.

Procedural requirements

The detailed regulations under the COMESA and EAC instruments reproduce the detailed procedural requirements set out in the three WTO Agreements on trade remedies. The SADC Trade Protocol says it doesn’t prevent the member states from using the WTO Agreements. The main procedural requirements are notification of the initiation of the investigation, and of the taking of provisional and final measures; but above all the undertaking of a thorough public investigation involving interested parties to establish that the trade remedy measures can be taken – proof of the act of dumping or benefit of a subsidy or a surge in imports; proof of injury or a threat of it (material in the case of dumping and subsidization and serious in the case of safeguards); proof of a causal link; and establishment of the parameters or the extent of the measures to be taken to ensure they do not exceed the margin of dumping or subsidy, or the duties and quotas necessary to prevent serious injury from a surge of imports. Regarding the form that safeguard measures can take, the Appellate Body has been of the following view:

In our view, the text of Article XIX:1(a) of the GATT 1994, read in its ordinary meaning and in its context, demonstrates that safeguard measures were intended by the drafters of the GATT to be matters out of the ordinary, to be matters of urgency, to be, in short, “emergency actions”. And, such “emergency actions” are to be invoked only in situations when, as a result of obligations incurred under the GATT 1994, an importing Member finds itself confronted with developments it had not “foreseen” or “expected” when it incurred that obligation. The remedy that Article XIX:1(a) allows in this situation is temporarily to “suspend the obligation in whole or in part or to withdraw or modify the concession”. Thus, Article XIX is clearly an extraordinary remedy.

The overarching preliminary legal and institutional requirement is that the country should have WTO-consistent national laws under which the trade remedies can be invoked and imposed, and institutions to undertake the investigations for and administration of the trade remedies; which should have been notified to the WTO. Except for Egypt and SACU countries, the tripartite member/partner states, for not having both the laws and the investigating authorities, may not qualify to use WTO Agreements on trade remedies on this critical ground.

Special and differential treatment

The WTO Agreements provide for some special and differential treatment for developing countries. Safeguard measures should not be taken against imports of a product from a developing country if less than 3% of total imports of that product, or unless total imports of the product from developing countries exceed 9% of total imports. Constructive remedies should be considered when taking antidumping measures against imports from developing countries. Developing countries in addition benefit from longer time frames for the application of trade remedies.

In the tripartite, building on this idea, if there are to be trade remedies, some consideration could be given to having a high threshold below which no such measures should be taken against imports from other tripartite member/partner states.

The level of and constraints to utilisation of REC regimes on trade remedies

No EAC partner state has used the EAC trade remedy provisions; and neither has any SADC member state invoked the SADC trade remedy provisions.

It can be noted that Egypt and South Africa have been the only users of trade remedy measures in the tripartite region, but they have invoked and applied their domestic laws, and not the COMESA, EAC or SADC trade remedy provisions. The national laws have been formulated for consistence with the WTO Agreements as the thrusting motivation, rather than consistence with the REC regimes.

In COMESA, Kenya has used a safeguard measure on sugar imports since 2002, which was due to expire in 2014 but was since extended to 2017, but the initiation of the safeguard measure was not under the detailed COMESA Trade Remedy Regulations; rather the measure was initiated under Article 61 of the Treaty which simply provides that a member state may take safeguard measures to last for up to one year after informing the Secretary General and the other member states, but the measure may be extended by the COMESA Council of Ministers if satisfied that the member state has taken necessary measures to overcome the imbalances for which the measure was taken. The extensions of the Kenya safeguard measure have been on the basis of recommendations from comprehensive reports prepared by the Secretariat confirming adherence to the conditions, which the Secretariat has produced after on-the-spot verifications and interviewing all relevant stakeholders in Kenya, and on the basis of the conditions set by the Council.

Kenya invoked Article 61 again for a safeguard on wheat flour in 2002, which ended in 2008. This safeguard, however, allowed for limited imports at zero duty from Egypt and Mauritius.

Zambia and Malawi each unsuccessfully attempted to invoke Article 61 for safeguard measures for wheat flour, because the studies commissioned concluded that there was no justification for taking the safeguard measures.

Mauritius, in November 2001 replaced the existing 0% duty rate on imports of Kapci paints from Egypt with a rate of 40%, under a bilateral arrangement between the two member states, instead of invoking Article 61 of the COMESA Treaty, which governs the invocation of safeguard measures. The grounds Mauritius advanced were that there was a surge of imports between 1997 and 2000, and some industry players had made representations against implementation of the 0% duty rate on 1 November 2000 when Mauritius started implementing the COMESA FTA. In a judgment delivered on 31 August 2013 in the case of Polytol Paints v The Government of Mauritius, Reference No.1 of 2012, the COMESA Court of Justice ruled that this was not consistent with the COMESA Treaty and ordered a refund of the customs duties paid by the importing company. The Court explained that bilateral trade arrangements between COMESA member states should aim to promote the objectives under the Treaty and not to reverse the progress achieved, inconsistently with the Treaty.

Some relevant literature on REC trade remedy regimes

A number of works have undertaken an analysis of the trade remedy provisions of the three RECs. The TradeMark Southern Africa (TMSA) training module on trade remedies[3] provides both a comprehensive analysis of the WTO rules and the REC provisions. It is suggested that the following two papers, in addition to the others cited in this paper, are fairly comprehensive on the matter of the REC regimes of trade remedies. Denner (2009) provides an exquisite analysis of the REC provisions in his publication on trade remedies and safeguards in southern and eastern Africa; as well of course as Ousseni Illy (2012) in his publication on the experience, challenges and prospects for trade remedies in Africa.

Some of the key points made in the literature are the following.

Except for Egypt and South Africa, tripartite member/partner states have not really utilized existing WTO or REC trade remedies in pursuing their development goals, and seeking to stave off the de-industrialization that resulted from the extensive trade liberalization especially since the 1980s. As Africa re-industrialises or booms[4], trade remedies against the rest of the world may just become as critical as they now are for the emerging powers (China, India, Brazil, Argentina and South Africa).

The constraints tripartite member/partner states face in this regard include the following: inexistence of national legal and institutional frameworks, high cost and lack of expertise, local producers’ weakness or lack of awareness or poor organization, and fear of repercussions from their donors who might get upset if trade remedies were applied against imports from their countries.

Another possible reason could be that until recently, most countries have enjoyed quite high bound tariff rates, which have provided the possibility of increasing applied rates up to the bound levels as measures to protect domestic industries. However, with the increase in bilateral and pluri-lateral FTAs that Africa’s countries are entering with partners, and in light of the waves of multilateral trade liberalization, this room for manoeuvre has been rapidly disappearing.

Ways should be found to address these constraints, including long term capacity building, legal reforms, establishment of regional committees and possibly investigating authorities, designation of trade or revenue ministries as the competent and investigating authorities, and use of private investigators who may be retired civil servants or other resource persons. In the TFTA, the secretariat could have a function of closely assisting the member/partner states in dealing with trade remedies.

If the tripartite is to have trade remedies, there could be merit in making appropriate modifications in the FTA rules on trade remedies, just as this has been the practice in other FTAs. This point is taken up in the next section on good practices in other FTAs. It is worth recalling again that the existing WTO-consistent REC regimes have hardly been used.

Good practices in other FTAs

The WTO Committee on Regional Trade Agreements established in 1996 has a mandate to examine regional trade agreements, including FTAs and customs unions that are notified to the WTO, as well as services liberalization agreements. The committee has been active, and has studied trends in the formulation of regional trade agreements. One such trend studied, has been how issues of trade remedies are addressed in RTAs.

Modification of WTO rules on trade remedies among RTA members

Sagara Nozomi back in 2002 already attempted to analyse the work of the committee in this area and the disputes decided by the WTO Appellate Body and Panels, and made the following findings. RTAs were taking different approaches, some provided for trade remedies in accordance with WTO rules, others eliminated them, while others modified or tightened the disciplines beyond the WTO rules to reduce use and abuse. On the whole, European (EU, EEA, EFTA), American (Canadian and Mercosur though NAFTA provides for trade remedies among the parties), and Oceania RTAs were making modifications or eliminating trade remedies. These mixed findings were cleaned up in a subsequent study in 2009 by Tania Voon, cited below.

Sagara concluded that provisions in RTAs that eliminated trade remedies were not found inconsistent with WTO rules; however, there were disputes regarding the correct procedures to be followed when a global safeguard measure was applied while excluding imports from members of the RTA. A framework for provisional safeguard measures can sooth the liberalization process in RTAs if import surges are anticipated. Antidumping and subsidies countervailing measures can be abolished in RTAs in light of substitutes such as competition policies and also given that GATT Article 24 calls for the elimination of restrictive regulations of commerce among members of a free trade area or customs union.

The numbers

In his survey of more than 150 RTAs around November 2009, Tania Voon made the following findings:

25 RTAs did not mention the WTO trade remedy Agreements or made no significant modifications;

28 RTAs provided for bilateral safeguards but in accordance with WTO rules;

66 RTAs made procedural changes to WTO rules and provided additional rules on bilateral safeguard measures; and

8 RTAs restricted the application of antidumping measures, 4 the application of subsidies countervailing measures, and 30 the application of global safeguard measures of which 4 prohibited both global and bilateral safeguards. (Voon, 2010, p. 37-9)

This analysis would appear to suggest, in terms of preponderance of numbers, that practice is tending towards making modification to WTO rules (66 RTAs) or even restriction of trade remedies (8+4+30); in contrast to those that maintain WTO rules (25) or provide for bilateral safeguards in accordance with WTO rules (28). Before moving on to the WTO law on these different approaches, the next section deals with the drafting techniques carrying those approaches.

Text for the different approaches

RTAs that maintain the WTO trade remedies either remain silent on the matter, or contain a provision to the effect that the RTA does not affect the rights and obligations of the parties under the WTO Agreement, or explicitly require member states to use WTO Agreements on trade remedies, or reproduce the WTO provisions.

RTAs that modify the WTO Agreements on trade remedies can contain explicit provisions that omit some of the requirements in the WTO Agreements, for instance, omitting the requirement for “unforeseen circumstances” in the RTA as a pre-condition for taking a safeguard measure (it has been argued that any negotiator of a trade agreement should expect that trade liberalization will result in increased imports and increased trade, and therefore should be deemed to have foreseen import surges, except perhaps the “serious” injury to domestic industries for which there should be a remedy even if the import surges were foreseen); abridging the time frames; limiting the actual measures to tariffs only and excluding quotas and price undertakings (the idea of the tariff-only approach is to promote transparency and tariffication as a means towards predictability and better planning of production costs, and to reduce rent seeking and political interference); and providing for high thresholds below which the measures should not be taken in order not to reduce trade as a result of generous use of trade remedies. It is absolutely important to highlight that such modifications would only apply among the members of the RTA under that agreement; but not to non-members of the RTA that are WTO Members. Any trade remedy measures against non-members of the RTA that are WTO members would need to be in accordance with the WTO Agreements.

Provisions that tighten the disciplines could additionally take the form of limiting the trade remedies to listed products or limiting the measures to products on which tariff phase outs have not reached zero (that is, during the transition period), requiring consultations before application of the measures, or providing for enhanced notification requirements as additional hoops to clear before the trade remedy can be invoked and applied.

RTAs that restrict the trade remedies may explicitly state that no trade remedy measures may be taken against imports from members of the RTAs, or provide for harmonized and common behind-the-border measures, or provide for free factor movement, or provide that trade remedies may only be taken “when no mutually acceptable alternative course of action has been determined by the Member States”, or link the abolition of trade remedies with competition rules: for instance,

“A Party shall not apply anti-dumping measures as provided for under the WTO Agreement on Implementation of Article VI of the GATT 1994 in relation to goods of a Party. The Parties recognize that the effective implementation of competition rules may address economic causes leading to dumping”.

Regarding safeguards, NAFTA for instance provides that,

Any Party taking an emergency action under Article XIX or any such agreement shall exclude imports of a good from each other Party from the action unless:

Imports from a Party, considered individually, account for a substantial share of total imports; and

Imports from a Party, considered individually, or in exceptional circumstances imports from Parties considered collectively, contribute importantly to the serious injury, or threat thereof, caused by imports.

The TFTA negotiations therefore have a range of options; it would of course be best to take the one that makes the most sense and taking the practice in other RTAs into account.

Does GATT Article 24 provide for elimination of trade remedies in RTAs?

This has been a vexed legal question. It has arisen in disputes at the WTO when a country has excluded members of the FTA or customs union it belongs to from the application of a safeguard measure, pleading the FTA or customs union as the defence or excuse; notably the US pleading NAFTA as a free trade area and Argentina pleading Mercosur as a customs union. The question has arisen also in the critical discussion on whether RTAs can eliminate trade remedies among themselves despite the WTO Agreements.

Article 41(1) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which has been used and observed by the WTO Appellate Body and Panels, provides for inter se modifications to the WTO Agreements, that is, modifications under an agreement entered by a group of WTO members among themselves and to apply only among themselves; for it says:

Two or more of the parties to a multilateral treaty may conclude an agreement to modify the treaty as between themselves alone if:

-

The possibility of such a modification is provided for by the treaty; or

-

The modification in question is not prohibited by the treaty and:

-

Does not affect the enjoyment by the other parties of their rights under the treaty or the performance of their obligations;

-

Does not relate to a provision, derogation from which is incompatible with the effective execution of the object and purpose of the treaty as a whole.

-

On the basis of these provisions of the Vienna Convention, Tania Voon, in a definitive paper on the subject, concluded that:

Article XXIV of the GATT 1994 confirms that Members may enter RTAs modifying their WTO obligations, subject to the conditions laid out in that provision and the rest of the WTO agreements. Specifically, Article XXIV:5 states that the “provisions of this Agreement shall not prevent, as between the territories of Members, the formation of a customs union or of a free-trade area or the adoption of an interim agreement necessary for the formation of a customs union or of a free-trade area…”. (Voon, 2010, p.26)

On its part, the WTO Appellate Body has had occasion to address this matter in quite some informative detail that can provide sufficient guidance.

The point of departure is that there must be no intention on the part of the member/partner states to raise barriers to trade with third countries, but rather, the whole purpose of the provisions of the TFTA, including the provisions on trade remedies or how they are addressed, should be to facilitate trade among the member/partner states within the framework of the TFTA. WTO jurisprudence has been consistent that the purpose of the RTA, the FTA in the case of the tripartite, should be to facilitate trade among the tripartite member/partner states, and the TFTA should do this in a manner that does not raise barriers to trade with third countries not members of the TFTA. The Appellate Body has been consistent on this:

According to paragraph 4 [of GATT Article 24], the purpose of a customs union [read FTA] is “to facilitate trade” between the constituent members and “not to raise barriers to the trade” with third countries. This objective demands that a balance be struck by the constituent members of a customs union. A customs union should facilitate trade within the customs union, but it should not do so in a way that raises barriers to trade with third countries. We note that the Understanding on Article XXIV explicitly reaffirms this purpose of a customs union, and states that in the formation or enlargement of a customs union, the constituent members should “to the greatest possible extent avoid creating adverse effects on the trade of other Members”.

With this in mind, the TFTA can operate as an exception to the WTO rules on non-discrimination, specifically the WTO MFN rule and any other rule in the GATT 1994. The TFTA can so operate as an exception on the basis of GATT Article 24 (or the Enabling Clause). As the Appellate Body has stated consistently:

… in examining the text of the chapeau to establish its ordinary meaning, we note that the chapeau states that the provisions of the GATT 1994 “shall not prevent” the formation of a customs union. We read this to mean that the provisions of the GATT 1994 shall not make impossible the formation of a customs union [read FTA]. Thus, the chapeau makes it clear that Article XXIV may, under certain conditions, justify the adoption of a measure which is inconsistent with certain other GATT provisions, and may be invoked as a possible “defence” to a finding of inconsistency.

If one wonders whether this idea of GATT Article 24 operating as an exception applies to the WTO Agreements on trade remedies, the Appellate Body has resolved this issue by explaining that GATT 1994 incorporated the old GATT 1947 and the new Agreements relating to trade in goods, including the WTO Agreements on trade remedies. The exception under GATT Article 24 therefore operates in respect of the entire GATT 1994, including the Agreements on trade remedies:

Thus, the GATT 1994 is not the GATT 1947. It is “legally distinct” from the GATT 1947. The GATT 1994 and the Agreement on Safeguards are both Multilateral Agreements on Trade in Goods contained in Annex 1A of the WTO Agreement, and, as such, are both “integral parts” of the same treaty, the WTO Agreement, that are “binding on all Members”. Therefore, the provisions of Article XIX of the GATT 1994 and the provisions of the Agreement on Safeguards are all provisions of one treaty, the WTO Agreement. They entered into force as part of that treaty at the same time. They apply equally and are equally binding on all WTO Members. And, as these provisions relate to the same thing, namely the application by Members of safeguard measures, the Panel was correct in saying that “Article XIX of GATT and the Safeguards Agreement must a fortiori be read as representing an inseparable package of rights and disciplines which have to be considered in conjunction.”

Or, again, as the Appellate Body similarly decided regarding the Antidumping Agreement:

… Article VI of the GATT 1994 and the Anti-Dumping Agreement are part of the same treaty, the WTO Agreement. As its full title indicates, the Anti-Dumping Agreement is an “Agreement on Implementation of Article VI of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994”. Accordingly, Article VI must be read in conjunction with the provisions of the Anti-Dumping Agreement, including Art. 9.

It is common ground among scholars that trade remedies are “restrictive regulations of commerce” within the meaning of GATT Article 24. However, there are two strongly opposed legal views on whether or not they should be eliminated in FTAs and customs union. One view is that they should, because GATT Article 24 requires “duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce” to be eliminated in FTAs and customs unions on substantially all trade among the members of the FTA or the customs union. The other view is they can be maintained. The bone of contention arises from the interpretation of paragraph 8(b) of GATT Article 24, which states that,

A free-trade area shall be understood to mean a group of two or more customs territories in which the duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce (except, where necessary, those permitted under Articles XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV and XX) are eliminated on substantially all the trade between the constituent territories in products originating in such territories.

Because the excepted provisions in brackets which can be maintained in the FTA, where necessary, do not include the GATT Articles on trade remedies, namely, Article VI, XVI and XIX (6, 16 and 19), has been the basis for the argument that these trade remedies should also be eliminated as restrictive regulations of commerce. But the other side has responded that the list of excepted provisions is only illustrative and there was no explicit intention or decision not to mention the provisions on trade remedies. Tania Voon’s analysis indicates that this view is factually incorrect, as the drafting history shows that the matter of the list of exceptions was considered and the trade remedy provisions were omitted from the list. This should settle the matter.

However, this position means that trade remedies as restrictive regulations of commerce, are subject to the overall requirement that duties and the restrictive regulations of commerce be eliminated on “substantially all the trade”; raising another troublesome issue. While the Appellate Body has avoided producing an explicitly quantitative position on what constitutes “substantially all trade”, it has at least provided the following guidance:

Neither the GATT CONTRACTING PARTIES nor the WTO Members have ever reached an agreement on the interpretation of the term ‘substantially’ in this provision. It is clear, though, that ‘substantially all the trade’ is not the same as all the trade, and also that ‘substantially all the trade’ is something considerably more than merely some of the trade. We note also that the terms of sub-paragraph 8(a)(i) provide that members of a customs union may maintain, where necessary, in their internal trade, certain restrictive regulations of commerce that are otherwise permitted under Articles XI through XV and under Article XX of the GATT 1994. Thus, we agree with the Panel that the terms of sub-paragraph 8(a)(i) offer ‘some flexibility’ to the constituent members of a customs union when liberalizing their internal trade in accordance with this subparagraph. Yet we caution that the degree of ‘flexibility’ that sub-paragraph 8(a)(i) allows is limited by the requirement that ‘duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce’ be ‘eliminated with respect to substantially all’ internal trade.

This can be understood to mean that a decision on whether or not to have trade remedies in the FTA or customs union should be based on an evaluation of whether the requirement of eliminating other restrictive regulations of commerce to substantially all the trade will be met. This would mean that the FTA or customs union that allows extensive use of trade remedies would not meet this requirement, while the one which eliminates them or keeps them to a minimum would be more likely to meet the requirement.

As the Appellate Body has said:

With respect to “other regulations of commerce”, Article XXIV:5(a) requires that those applied by the constituent members after the formation of the customs union [read FTA] “shall not on the whole be … more restrictive than the general incidence” of the regulations of commerce that were applied by each of the constituent members before the formation of the customs union. Paragraph 2 of the Understanding on Article XXIV explicitly recognizes that the quantification and aggregation of regulations of commerce other than duties may be difficult, and, therefore, states that “for the purpose of the overall assessment of the incidence of other regulations of commerce for which quantification and aggregation are difficult, the examination of individual measures, regulations, products covered and trade flows affected may be required”. We agree with the Panel that the terms of Article XXIV:5(a), as elaborated and clarified by paragraph 2 of the Understanding on Article XXIV, provide:

… that the effects of the resulting trade measures and policies of the new regional agreement shall not be more trade restrictive, overall, than were the constituent countries’ previous trade policies. ...

Now, to explicitly answer the question of whether the FTA can exempt its members from the application of a global safeguard against other members of the FTA: regarding WTO members that are not in the TFTA, the rules of the WTO Safeguards Agreement must be complied with by member/partner states in imposing safeguard measures, that is, including the rule that the safeguard should be global, on a non-discriminatory basis. However, if the investigation explicitly shows that imports from the third countries, excluding imports from tripartite member/partner states, satisfy the conditions for applying the safeguard measure and an explicit finding to that effect is made, then the safeguard measure applied by a tripartite member/ partner state can exclude imports from other tripartite member/partner states. The Appellate Body has reached this result, while avoiding a direct answer to the issue, by developing the rule now known as “parallelism”:

… we do not prejudge whether Article 2.2 of the Agreement on Safeguards permits a Member to exclude imports originating in member states of a free-trade area from the scope of a safeguard measure. We need not, and so do not, rule on the question whether Article XXIV of the GATT 1994 permits exempting imports originating in a partner of a free-trade area from a measure in departure from Article 2.2 of the Agreement on Safeguards. The question of whether Article XXIV of the GATT 1994 serves as an exception to Article 2.2 of the Agreement on Safeguards becomes relevant in only two possible circumstances. One is when, in the investigation by the competent authorities of a WTO Member, the imports that are exempted from the safeguard measure are not considered in the determination of serious injury. The other is when, in such an investigation, the imports that are exempted from the safeguard measure are considered in the determination of serious injury, and the competent authorities have also established explicitly, through a reasoned and adequate explanation, that imports from sources outside the free-trade area, alone, satisfied the conditions for the application of a safeguard measure, as set out in Article 2.1 and elaborated in Article 4.2. ...

In conclusion then, as a legal matter, GATT Article 24 provides the possibility of excluding trade remedies from application among members of the FTA and customs union, the TFTA in this case.

Dr Francis Mangeni is Director of Trade, Customs and Monetary Affairs at the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA). The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of tralac.

This article follows others by the same author:

[1] Tripartite Member/Partner States that are WTO Members are the following: Angola (1996), Botswana (1995), Burundi (1995), Congo DR (1997), Djibouti (1995), Egypt (1995), Kenya (1995), Lesotho (1995), Madagascar (1995), Malawi (1995), Mauritius (1995), Mozambique (1995), Namibia (1995), Rwanda (1996), South Africa (1995), Swaziland (1995), Tanzania (1995), Uganda (1995), Zambia (1995), and Zimbabwe (1995). Observers are Comoros, Ethiopia, Libya, Seychelles and Sudan; while Eritrea is neither a member nor an observer. South Sudan is yet to join COMESA, EAC or SADC, though it has been recognized at the UN and African Union as a new nation.

[2] This section draws on the 2012 Annual Reports of the WTO Committees covering trade remedies, available at www.wto.org

[3] Freely available at http://trademarksa.org/resources/trade-negotiation-capacity-building; for comparison or contrast, please see the Asian Development Bank toolkit on trade remedies also freely available at http://www.adb.org/publications/trade-remedies-tool-kit

[4] One of the latest interesting articulation of Africa rising, is Charles Robertson’s The Fastest Billion, Renaissance Capital, October 2012. As usual, there must be some caution, and a pertinent one is that development for the last 100 years has been technology-led, and so it must in Africa as well, indeed as eloquently explained by Peter Diamandis and Steven Kotler in their Abundance – The Future is Better Than You Think, 2012.

References

Willemien Denner, Trade Remedies and safeguards in southern and eastern Africa, Chapter 3 in Monitoring Regional Integration in Southern Africa Yearbook 2009

Luz Helena Beltran Gomez, Is South Africa using trade remedies as a protectionist measure? Reflections on a court case: International Trade Administration Commission v SCAW South Africa [2010] ZACC 6 (9 March 2010), Derecho Economico Internacional

Ousseini Illy, Trade Remedies in Africa: Experience, Challenges and Prospects, Oxford University Global Economic Governance Working Paper No. 2012/70 of June 2012

Sagara Nozomi, Provisions for Trade Remedy Measures (Anti-dumping, Countervailing and Safeguard Measures) in Preferential Trade Agreements, Regional Institute of Economy Trade and Industry Discussion Paper Series 02-E-013, (2002).

Alan O Sykes, Trade Remedy Laws, Law School of the University of Chicago, John M Olin & Economics Working Paper No. 240 (2d Series), April 2005

Tania Voon, Eliminating Trade Remedies from the WTO: Lessons from Regional Trade Agreements, Georgetown University Law Center, 2010

Wentong Zheng, Reforming Trade Remedies, 34 Mich J. Int’l L. 151 (2012)