News

Trade Policy Framework: Angola

The main challenge facing Angola in participating in international trade is the continued over-reliance on exports of one commodity, petroleum, which accounted for 99 per cent of total merchandize exports of $62.4 billion in 2014 and manufactured goods accounting for only 0.1 per cent. Rather than shrink, the proportion of exports of primary commodities has increased in the past 20 years.

While it has diversified its export market from traditional developed countries, namely the European Union and the United States of America, to China, Angola has not correspondingly diversified its exported products. The central question remains how the country can improve its trade portfolio for economic diversification.

Angola’s economy has been growing progressively over the last 20 years. Between 2004 and 2009, growth was in the range of 15-20 per cent but there is no evidence that that growth supported export diversification to a large extent. Now growth has declined from about 18 per cent in 2008 to about 2 per cent in 2014, and this performance may adversely affect export diversification efforts.

The study examines Angola’s participation in international trade and its existing trade policy, and seeks to recommend some areas of policy changes that may help the Government to improve its trade performance and bring about inclusive development. As regards merchandise trade, the study identifies several sectors that could be usefully explored for the country’s export diversification efforts, particularly through accelerated agro-based industries development. These include coffee, tea, fruits, fruit juice, vegetables, maize, cassava, sugar cane, cotton, floriculture, sawdust briquettes, fisheries, palm oil and natural rubber. Some of these sectors have been important in improving export performance of some developing countries such as Malaysia in palm oil and Viet Nam in coffee. Other recommendations centre on improving capacities with supportive services infrastructures, and regulatory and institutional framework, improving and strengthening trade related fundamentals.

As regards trade services, the study identifies some key services sectors in which reforms and improvement in the supply side would be necessary to boost trade. These include the energy, financial, construction, tourism, telecommunications and transport services. For example, it calls for improved quality of transportation and increased supply of road cargo transportation. For telecommunications services, it calls for raising funds to create a broadband infrastructure in order to connect all urban and rural geographic regions of the country and establish connections with the regional infrastructures supporting the development of telecommunications. For tourism services, it calls for development of the Angolan tourism services through quality products, incorporating the regional, cultural and natural diversity and to stimulate and facilitate the consumption of Angolan tourism products in the national, intraregional and international market.

Participation in Trade

Angola’s economy continues to depend on petroleum oil. Oil and gas made up the largest share (46 per cent) of the country’s GDP in 2010, which was, nonetheless, a reduction from 56 per cent in 2006. In trade, petroleum oil, almost all of it as crude oil, accounts for about 96 per cent of total exports and 80 per cent of fiscal revenue. Overdependence on exports of oil has disincentivized the country from moving into the global value chain and participating in exports of processed goods and value added services. This poses a major challenge to building economic resilience to help the country to weather external shocks manifested in global price fluctuations of petroleum oil, which impact negatively on the economy from time to time.

The contribution of value added services to GDP, which was substantial in 1980 (45 per cent), halved to 27.5 per cent in 2012.

The contribution of the agriculture sector to GDP also declined from 14.4 per cent in 1980 to 9.4 per cent in 2012. Notwithstanding, agriculture remains a very important sector of the economy, on which most of the rural population depends on for their livelihood. The agricultural sector in Angola comprises forestry, fisheries, livestock and the cultivation of bananas, plantains, sugarcane, coffee, sisal, corn, cotton, manioc, tobacco and vegetables. Prior to gaining independence, Angola was self-sufficient in food and exported cash crops like coffee and sugar.

Angola is no longer self-sufficient in food, and the production of crops has declined. Nevertheless, fertile soils (about 58 million hectares of land) and a favourable climate present an attractive opportunity for investment in agriculture and huge potential for its growth to pre-independence levels and beyond. Major constraints, however, are the need for large areas of agricultural land to be demined and poor infrastructure (roads, railway, ports and warehousing).

The manufacturing sector accounted for only 6.1 per cent of GDP in 2012, which was a decline from 9.2 per cent in 1980.

The construction sector accounted for 7.8 per cent of GDP in 2012, which is an increase from 4.7 per cent in 1980. The renovation of domestic infrastructure and construction of new infrastructure, which are necessary to cater to an expanding and diversifying economy, is expected to boost the growth of this sector and its share of GDP.

In terms of human resource development, it is important to note that commerce is largely dominated by the informal sector, which accounts for 60 per cent of the population and consists largely of displaced persons from the war and migrants to urban areas. While the oil sector provides job opportunities for Angolans, these remain limited and have not grown in direct proportion to increases in output. Despite strong economic growth, underemployment remains a major challenge and much of Angola’s population of 19 million people continue to live below the $1/day poverty line. There is a widespread lack of qualified human resources, which acts as a major constraint on growth in the medium term. Angola is currently dependent on the scientific and technological skills of foreigners, without which the source of Angola’s economic growth would remain trapped. Some of the largest foreign companies in Angola have education programmes for Angolan nationals with an emphasis on science and technology.

In the Country Strategy Paper 2011-2015, the African Development Bank (ADB) identifies the Government’s main objective as to promote and accelerate growth and competitiveness through economic diversification and poverty reduction. The Government faces major challenges in translating this important objective into budgetary support to achieve export value addition and diversification and ensuring trade plays contributes to the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), including job creation, poverty reduction, raising living standards for the poor and vulnerable and improving education and health.

Trends in Angola’s trade in goods

International trade can play an important role in Angola’s economic development. Exports of goods and services accounted for almost 70 per cent of GDP in 2012, and imports for about 46 per cent. International trade is the single most important source of employment and finance for imports, especially in the productive sector. To date, however, exports of crude petroleum oils dominate the export mix and reflect the lack of structural transformation in the Angolan economy. This has resulted in a narrow productive base and an economy that is highly susceptible to price volatilities in the international petroleum oils market.

Angola has consistently recorded a trade surplus. This is despite its propensity to buy all its necessities from abroad, even in cases where the country has a potential comparative advantage in producing them. This may be due to the war and the appreciation in the real exchange rate of the Angolan kwanza as a result of Dutch Disease, which has made the country’s imports cheaper relative to its exports.

Trade surpluses have strengthened the country’s balance of payments, which has meant less borrowing to finance its development programmes and other societal needs.

Exports and imports

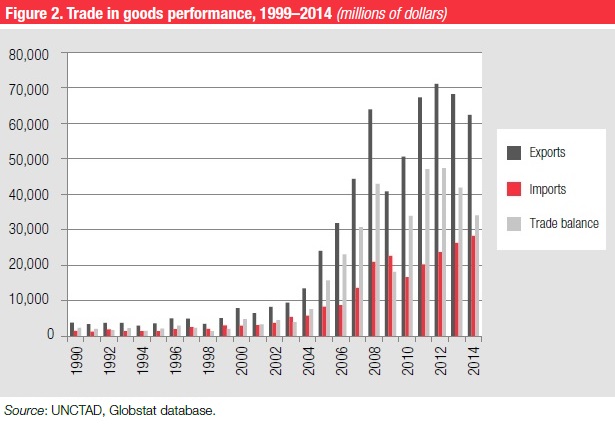

Angola’s global exports expanded from $8 billion in 2000 to $69 billion in 2013, although this was a drop from $71 billion in the previous year that may have been caused by a drop in global oil prices. But in 2014 exports dropped to $62 billion. In the same period, imports increased from $3 billion to $24 billion and in 2014 increased further to about $ 27 billion, at an average annual growth rate of 24 per cent. The trade balance increased from $5 billion in 2000 to $44 billion in 2013 and dropped to $32 billion in 2014, at an annual average growth rate of about 29 per cent. There was a drop in the trade balance from $47 billion in 2012 to $44 billion in 2013.

Between 2008 and 2009, exports slumped from $72 billion in 2008 to $41 billion in 2009, as a result of slowing demand and the corresponding 2009 slump in oil prices from an average of nearly $100 a barrel in 2008 to just over $50 due to the global economic crisis. This was a decline of 43 per cent. Imports also fell, albeit by a smaller margin of about 10 per cent, from $23 billion to $21 billion. Consequentially, total trade and the balance of trade also recorded sharp declines, while still remaining positive.

Angola is one of the few African countries that have continuously recorded trade surpluses. For instance, in 2008 its trade surplus was $51 billion, compared with $5 billion in 2000, a tenfold increase over this period. In 2013, the trade surplus was $43 billion. Increased trade surpluses help leverage external resources to support economic growth in other areas, in particular economic transformation that enables the country to diversify its exports and add value. The 2008-2009 economic crisis pushed Angola’s current account and budget into deficit.

The economic crisis had a pernicious impact on Angola’s trade and development. For Angola, as a single-commodity-dependent country, it was also a reminder of the perennial threat to its economic development and the need to expand its productive capacities and upgrade the necessary fundamentals to move into value addition and diversification and boost exports.

After a period of global crisis that shrank exports to almost half of those recorded in 2008-2009, Angola’s trade is rebounding (figure 2), with exports reaching almost $70 billion in 2013. However, in light of the incipient global economic recovery, this may be unsustainable. The recovery of world trade decelerated in the second half of 2010 and significant volatility remains in primary commodity markets.

The country’s balance of payments still registers a trade balance surplus, despite a decrease of 11.6 per cent from 2012 to 2013 in that surplus, which went from $47.4 billion to $41.9 billion due to increased imports and reduced exports, whose percentage changes were 11.1 per cent and -4.0 per cent, respectively.

Share of trade in GDP

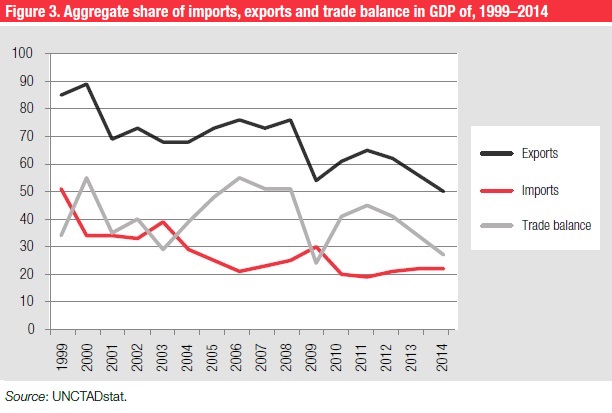

International trade is playing an important role in the country’s economy and its high degree of openness to trade. Figure 3 shows the share of imports, exports and trade balance in GDP for goods for the period 1999-2014. The share of exports surpassed that of imports and trade balance respectively while that of exports was higher than imports. The share of exports, imports and the trade balance in GDP declined drastically over the years due to the impact of drops in global oil prices heightened by the past economic crisis.

Exports of manufactured goods

Angola’s share of world exports of manufactured goods is marginal, and there is a glaring imbalance in exports of primary commodities. The share of exports of manufactured goods is only 0.1 per cent, compared with 99 per cent for primary commodities in 2014. While the share of exports of manufactured goods has remained flat for many years, the share of primary commodities has been rising, suggesting that the strategy to diversify exports and add value is still far from realization.

Angola’s sectoral export performance varies significantly. The role of crude oil in trade has not changed significantly over the years. In 1995, it accounted for almost 94 per cent of total exports, increasing to almost 99 per cent in 2014. In total, petroleum oils accounted for 98 per cent of total exports in 2014. Food items account for only 0.04 per cent, agriculture raw materials for only 0.01 per cent, and ores and metals for only 0.20 per cent.

In terms of GDP, crude oil accounted for 103 per cent in 2005 (2009: 99 per cent), while diamonds accounted for only 3 per cent in 2005 (2009: 2 per cent), and other products for 4 per cent in 2005 (2009: 3 per cent).

Structural weaknesses in supply and productive capacities that seriously inhibit production and value addition may be the main factors contributing to the underperformance of non-traditional products. Furthermore, non-tariff barriers (NTBs) in export markets may also have limited exports, although this has to be substantiated, as exports such as raw coffee from Angola enjoy trade preferences at zero duty in the United States and the European Union.

The country has diversified its export markets and no longer depends mainly on developed countries. Seven countries make up Angola’s major export markets, and account for 86 per cent of the world market. This market diversification has not been followed by corresponding diversification in exports, as the country continues to rely on exports of petroleum products.

Angola’s main export markets are the United States, China, Taiwan Province of China, India, France and Canada. In 2003, these six markets accounted for 77 per cent of total global exports of nearly $10 billion, of which the United States, the largest market, represented 38 per cent, followed by China with 22 per cent, Taiwan Province of China with 8 per cent, and France and India with 6 per cent and 3 per cent respectively.

In 2013, there was a remarkable change regarding China, which accounted for 48 per cent of Angola’s $68 billion total exports, followed by India with 10 per cent, the United States with 7 per cent and Canada and Taiwan with 5 per cent each.

Regional trade

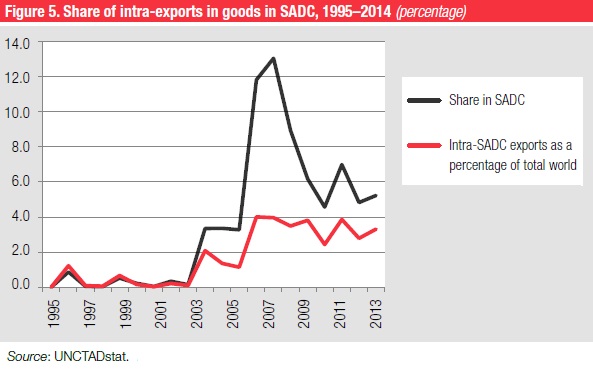

Angola’s main regional trading activities take place within SADC, which comprises 15 member States.

Like most other African countries, it exports more to non-partners than it does within the SADC region. In 2014, its exports within SADC accounted for only 3.0 per cent of its global exports, showing that the country is very far from integrating at the regional level. This point is also supported by the fact that its share of total intra-SADC exports declined steeply from about 13 per cent in 2009 to about 5.0 per cent in 2014 (figure 5).

Trade Policy Framework

Trade policies can only meet their desired objectives when they are implemented within a broader framework of sustainable macroeconomic and development policies and an enabling environment that engenders economic growth, and trade growth and expansion. It is in this context, that a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis has been used to understand the main challenges confronting Angola’s economic and trade sector and the Government’s stated objective of expanding the productive base of the economy, and harnessing gains through trade growth and expansion to meet the MDGs. Chapter IV contains policy recommendations that ensue from this analysis.

Strengths

-

Angola has abundant natural resources, including large reserves of oil, huge potential as a producer of LNG and fertile land;

-

It has considerable agricultural, fisheries and manufacturing potential;

-

The Government’s vision is to expand the productive base of the economy into agriculture, fisheries, and manufacturing;

-

A number of new and revised laws redefine its trade and investment framework, such as the new Customs Code, and legislation that adopts the provisions of the WTO Agreement on Customs Valuation. Some new sectoral policies and strategies have also been formulated, albeit in a fragmented and not comprehensive manner.

Weaknesses

-

An unfriendly business environment, including long delays in processing approvals, high cost of doing business and relatively high corruption levels;

-

Angola has structural weaknesses in the economy, especially in fundamentals such as infrastructure, skilled and trained human resources, low agricultural productivity and diversification, that could derail efforts to spur economic growth and trade expansion. The lack of access to finance and underdeveloped infrastructure are severe constraints to business in the country. Angola has higher costs to export than both the low income average and the sub-Saharan average.

-

Overdependence on oil exports and lack of access to key international production and distribution chains and networks;

-

The lack of economic opportunities in the rural sectors limits its fuller integration into the economy.

Opportunities

-

Fertile soils and a favourable climate present an attractive opportunity for investment in agriculture;

-

The Government’s firm commitment to address corruption in the form of zero tolerance is a positive signal to make the country a more attractive investment destination for both domestic and foreign investments;

-

The ongoing renovation and upgrading of infrastructure destroyed in the long civil war should boost long-term economic and trade growth. Likewise, enabling greater access to electricity supply would spur economic and trade growth and expansion;

-

The availability of a wide range of fiscal and tax incentives for both domestic and foreign investors that are not only limited to the oil and diamond sectors to encourage diversification of the economy and trade;

-

Preferential treatment in the markets of many industrialized countries under GSP, including the European Union EBA Initiative, and the United States AGOA. Angola also participates in a number of trade agreements and is a member of SADC and COMESA;

-

South-South cooperation presents new financial, technical and technological opportunities that could be converted into expanded investment and technological support for the development of supply and productive base, export value addition and diversification.

Threats

-

Large areas of agricultural land need to be demined to make it available for agricultural and economic development;

-

Dutch disease: Having to restart its non-oil economy after the long civil war in an environment of real exchange rate appreciation presents challenges to policymakers in their efforts to expand the productive base of the economy into a broader range of goods and services. This threat is also applicable to new start-up businesses;

-

The constant threats arising from global oil price volatility impact negatively on export revenues from its dominant product;

-

Global environmental threats, including climate change, that could affect agricultural production and prices and food security;

-

Increasing threat of NTMs, especially technical standards and SPS being used as NTBs against the country’s exports, including those standards set by the private sector;

-

Disease, hunger and other social problems are having a negative impact on the economy.

The analysis in chapters I, II and III and the scanning of Angola’s internal and external environments through SWOT, reveals that structural weaknesses in its supply and productive capacities constitute the main challenge confronting Angola in effectively participating in international trade in goods and services, especially entry into the global manufacturing value chain and networks where it would be able to diversify and add value to its exports and move away from primary commodity dependence. Chapter I confirms Angola’s export dependence on oil and marginal performance and neglect of the non-oil sector where structural change, economic transformation and real productivity in terms of value addition and diversification should be made, and jobs created and poverty reduced.

Hence, in order for the Angolan economy to benefit more fully from trade and investment opportunities, the Government should intensify its efforts at creating an enabling environment for all stakeholders. This would include ensuring macroeconomic stability, strengthening institutional and regulatory frameworks, intensifying the development of human resources, enhancing technology, renovating dilapidated infrastructure and investing in new efficient infrastructure, such as highways, roads, ports, airports and increasing access to electricity. A quantum leap into the twenty-first century in transforming the economy and in catching up with its neighbours, for example, South Africa, is necessary. This effort can be bolstered through investment in ICT, particularly in broadband technology. This would also be a natural development of the efforts already instituted in opening up the telecommunications sector to competition from private investors.

The enabling environment would be capable of supporting and facilitating the diversification of the production base and export mix, export competitiveness, and expanded and quality exports through greater investments, both domestic and foreign. It can also cushion the economy from future economic shocks that often beset Angola as an almost single commodity producer. The economic crisis in 2008 resulted in declining exports and lower export earnings of $30 billion between 2008 and 2009, compared with $70 billion, and this perniciously affected the overall balance of payments and GDP. A resilient Angolan economy rooted in strong fundamentals and supported by equally strong trade policy and institutional and regulatory frameworks is likely to withstand future threats and promote inclusive development.

To elaborate and implement a sound trade policy, Angola would need to ensure that this is done within the context of a broader national development strategy, including internationally agreed development goals such as MDGs with an emphasis on human and institutional development and poverty reduction. Trade policy must embrace inclusiveness and national consensus involving all relevant stakeholders, including the private sector, women, the vulnerable and poor, rural and urban traders, non-State actors and the public. This will ensure national ownership.

In this context, it is recommended that the new trade policy and attendant policies, including investment opportunities, be packaged and branded as part of what could be termed “Angola’s Economic Transformation Agenda”. It is further recommended that this new trade policy be implemented as part of a vision aimed at helping the country graduate from its LDC status as defined by the United Nations within a specific time period.

The current buoyant performance of the oil sector in trade and its positive impact on the economy may not be sustainable in the longer term due to various external threats, including climate change. The ongoing debate in international circles on the possible negative environmental effects of hydrocarbon fuels, coupled with increasing efforts by importing countries to shift their energy mix to cleaner fuels, underscores the need for Angola to broaden its production and export mix.

This study was prepared at the request of the Government of Angola in order to assist the country in elaborating a trade policy framework. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Angola or of the United Nations Secretariat.