News

Approaching the CFTA services negotiations: Which way towards delivery by 2017?

What are the business challenges that need to be addressed in the CFTA services negotiations and how to engage with the private sector in this process? Is it possible for the agreement to embrace pro-competitive regulatory disciplines? What are the possible options for a successful conclusion by 2017?

The services sector is becoming a key driver of sustainable economic growth and structural transformation in African economies. The World Bank estimates that the sector accounts for 47 percent of gross domestic product and 37 percent of employment in average in African countries, while statistics from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) indicate a 6.6 percent average growth in total imports and exports for the sector in 2013. Nevertheless, services exports remain low for many countries, averaging 2.6 percent of global African exports over the last three decades. The assessment of Africa’s poor trade performance shows that numerous trade bottlenecks lie in the services sector. In 2012, the Africa Union’s (AU) Assembly of Heads of State and Government endorsed the Boost Intra-Africa Trade Strategy (BIAT), which outlines the benefits of an open market and the need to develop a competitive services sector. This is to be achieved, among others, through the establishment of the Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) by 2017.

The CFTA negotiations, which were launched in June 2015, will be conducted in two phases. While the first phase covers trade in goods and services, the second phase will focus on investment, intellectual property rights, and competition policy. Since the launch of the negotiations, the AU Commission (AUC) has been undertaking capacity building seminars to enhance the knowledge and negotiating skills on trade in services among policy-makers, negotiators, and private sector representatives. From these seminars, a general consensus seemed to emerge around the idea that market access and national treatment commitments should be complemented by sectoral regulatory disciplines in order to promote trade competition.

Engaging with the private sector to address business challenges

There have been efforts to raise awareness among the African business sector and coordinate its input in various trade negotiations, but its participation and engagement often remains limited. In a recent policy brief, UNCTAD suggests that in order to foster African integration, a bottom-up approach involving governments, the private sector, civil society, and the international community is necessary. The relation between those stakeholders should be reciprocal so as to nurture an incremental exchange of ideas, information, resources, and trust among them. Systematic engagement of the private sector in identifying business challenges and solutions would help to build a lasting business-oriented collaboration and accelerate the implementation of the agreement once negotiated.

Hence, there is a need to coordinate the participation of the private sector and establish a formal structure for its engagement in the framework of the CFTA negotiations. Insufficient private sector engagement may lead to nonacceptance of the agreement by businesses, as has happened in the case of the Tripartite free trade area (TFTA). So far, the AUC envisages the establishment of an African Business Council (ABC), which would serve as a platform for aggregating and articulating the views of the private sector. The ABC would collect, process, and present the views of the private and business operators from the continent. This issue of how the business sector is organised is of crucial importance, since it will influence the extent to which, and how effectively, the services negotiations will be able to address business challenges.

The underdevelopment of infrastructural and network services is among the business challenges that require regional agreement to coordinate national efforts. The CFTA agreement could be used to promote infrastructure development and secure governments’ commitments to invest in infrastructural services. Such a dynamic is important, as it will exert peer pressure among African governments for restructuring regulations in order to promote public-private partnership projects and encourage private sector provision of services. Also, burdensome entry visa procedures have often been cited as a limiting factor to the movement of services providers, traders, and investors in Africa. This constitute a further opportunity to reduce important trade barriers in the framework of the CFTA.

In addition, insufficient regulation and lack of transparency in the services sector has contributed to corruption as well as hampered the development of trade in services. For example, economic empowerment requirements have in many cases brought in policy reversals and contradictions in the regulations, which frustrates investors. Access to regulations governing the services sector in relation to business registration, licensing procedures, taxation, and profit repatriation policies is key in business decisions and minimises the loopholes for corruption. Additionally, governments need to protect consumer and public interests by ensuring that sound regulations promote fair competition among business operators. At the end of the day, predictable and market-oriented rules in the services sectors would help to promote intra-Africa trade by lowering the cost of doing business. Therefore, the CFTA services agreement could be used to encourage transparency and pro-competitive services regulation on the continent.

What is the current state of play?

Article 6 of the AU Treaty provides that the CFTA should be built on the achievements of the eight Regional Economic Communities (RECs) – i.e. the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the East African Community (EAC), the Economic Community of Western African States (ECOWAS), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (SAN-CED), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). However, progress in the liberalisation of trade in services in the various RECs has been rather limited.

So far, only COMESA, EAC, and SADC have achieved a comprehensive services agreement with positive list liberalisation schedules. Of the three, only SADC is negotiating some sectoral pro-competitive regulatory disciplines to complement market access and national treatment commitments. The West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), a sub-region of ECOWAS, has agreements covering market access commitments in dental, medical, accounting, legal, architectural, telecommunication, and transport services. The Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CAEMC), a sub-region of ECCAS, has cooperation agreements focusing on infrastructural development, but they do not include market access issues. Both the WAEMU and CAEMC sectoral agreements do not include pro-competitive regulatory commitments. With regard to the rest of the RECs, they do not have any form of services agreement yet. Additionally, the COMESA-EAC-SADC TFTA signed in 2015 is also envisaged as a stepping stone towards the establishment of the CFTA, but the negotiations on the trade in services component are yet to commence.

Except for Algeria, Comoros, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Libya, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Sudan, who have not acceded to the WTO yet, all other AU states have schedules of liberalisation under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). Countries such as Gambia and Lesotho made substantial GATS commitments but to date, they have received only limited investment in the services sector. This points to the fact that liberalisation schedules may not be a sufficient factor to promote trade or attract investment, which raises the following question: what else needs to be part of the equation in order to effectively boost intra-African trade in services? The schedules address only the trade rules, and assumes that supportive infrastructure and pro-trade sectoral and regulations exist.

The inclusion of regulatory disciplines in trade in services agreements seems to be the trend, as observed in the most recent free trade agreements (FTAs). For example, the EU Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAw) with the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) States and the EU-Korea FTA include a section on sectoral regulatory disciplines covering sectors of interest. Also, some regional FTAs such as the EU Single Market include regulatory disciplines covering broadcasting, financial, professional, telecommunications, and transport services, while the Caribbean Community Single Market settles for regional standards in agreed professions. The rationale behind this approach is to try to deal with regulatory challenges that cannot be addressed through schedules of commitments and to enhance balanced regulatory development and standards in the services sectors. Regulatory disciplines are particularly important for infrastructural and network services (e.g. communication, financial, energy, and transport sectors), where fair competition and access to distribution networks should be managed by independent bodies. However, there has been a slow take-up in the development of pro-competitive regulatory disciplines among African RECs, except for SADC. Therefore, the CFTA negotiations offer an entry point to promote the approach.

CFTA services liberalisation: The approach and possible structure of the agreement

The existing REC services agreements differ in terms of approach and architecture, which constitutes a challenge for establishing a common denominator as a starting point in the CFTA negotiations. The process of defining such a starting point would require a comprehensive sector audit to assess the state of liberalisation and sectoral regulatory gaps across the AU states. Nevertheless, different starting points could be explored, such as: (1) applying the liberalisation requirements by sector by building on the existing RECs and AU sectoral agreements; (2) building on the achievements of RECs, i.e. EAC, COMESA, SADC, or even TFTA if the process is finalised soon enough to be factored in the CFTA negotiations; (3) starting at the level of GATS commitments; and (4) starting with the current level of autonomous liberalisation in the member states.[1] Learning from the experience of other FTA negotiations, the CFTA process could set up a hybrid scheme to accommodate the different approaches used in the various RECs. The aim should be to increase the degree of services liberalisation achieved by existing RECs and extra-regional FTAs such as the EPAs and other bilateral FTAs.

For the AU, it should be feasible to agree by 2017 on a framework agreement, which would include a transparency list of applicable rules on the typical market access issues. Once this first main part of the CFTA services agreement is concluded, member states could thereafter negotiate pro-competitive sectoral regulatory disciplines to supplement the commitments contained in the transparency list.

The framework agreement would comprise general trade in services rules (i.e. most favoured nation treatment, market access, national treatment, transparency, the right to regulate and competition issues, etc.), other related matters (e.g. promotion of regional value chains, entry visas for services providers, etc.), the institutional framework and the transparency list for liberalisation commitments. The AU states could borrow a leaf from the approach used in the Asian Framework Agreement on Services, whereby specific liberalisation targets are set to be achieved over a given span of time. The CFTA negotiations on the services transparency list could proceed in different rounds, with specific targets for each round. They would aim at agreeing on: (1) clusters of sectors and modes of supply; (2) identified trade restrictive measures, by sector, that will be liberalised and which could be dealt with in a package; and (3) any additional criteria for commitments that would constitute progress in the process.

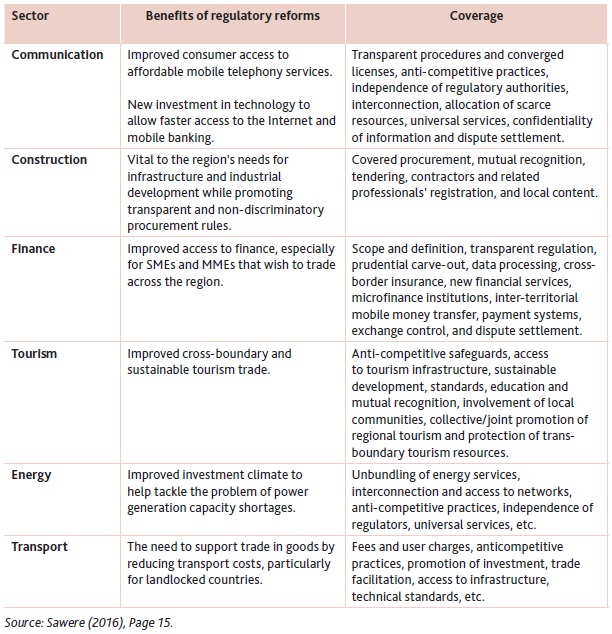

The sectoral regulatory frameworks should build on existing AU sectoral agreements and focus on trade-related and pro-competitive regulatory disciplines on transparency, anticompetitive practices, independence of regulators, local content and empowerment policies, human resources development, and regulatory cooperation (See table 1 below for illustrative examples in selected sectors).

Table 1: Possible Structure of the AU-CFTA Services Agreement - Sectoral regulatory framework

Which way forward?

The establishment of the CFTA provides an opportunity for the development of regional rules to boost intra-Africa trade by addressing business challenges in the services sectors. Although the process is yet to fully take off the ground, there is a recognition that engagement between governments and the private sector in the negotiations is necessary and will enhance implementation. There is an urgent need to fast-track the establishment of a private sector consultation mechanism and some form of capacity building for its effective engagement in the CFTA process. Also, since the starting point for the services negotiations is not clear yet, there is a need for taking stock and establishing the state of play both at the national and REC levels.

Since it might be difficult to achieve a comprehensive CFTA agreement on services by 2017, the negotiations could instead be undertaken in several rounds over a period of time. Specific targets could be set for each round. It should be possible to conclude the negotiations on a general framework agreement and an initial transparency list by 2017. The inclusion of pro-competitive sectoral regulations is vital in addressing sectoral challenges and would add value to market access and national treatment commitments. In the case of sectors where there are no AU agreements, sectoral disciplines could be developed on the basis of the illustrative examples shown in table 1. Supplementary or addendum agreements are recommended in areas of existing AU sectoral agreements to bridge any regulatory gaps and manage the inter-relations between agreements in case of disputes.

Viola Sawere is a Regional Trade Policy Adviser at the SADC Secretariat. David Ndolo is a PhD student in Law at Coventry University, UK.

This article is published under Bridges Africa, Volume 5 - Number 4, by the ICTSD.

[1] Sawere, Viola, (2016), Pro-Competitive Services Sector Regulation: A Possible Direction for The AU CFTA Agreement, Trade Law Centre (tralac), Cape Town, South Africa. Available at: http://www.tralac.org/images/docs/9229/s16wp032016-sawere-pro-competitive-services-sector-regulation-possible-direction-for-cfta-20160309-fin.pdf