News

In Africa, those who bet on China face fallout

Economic slowdown in China exacerbates strain for trading partners in Africa

As the global oil-price slump passed its one-year anniversary in June, Angola’s President José Eduardo dos Santos booked a trip to Beijing.

The long-serving autocrat hoped fresh loans and investment from China, Angola’s top trading partner, would buoy his country’s oil-dependent economy through choppy waters, according to financiers who do business with his government. On a weeklong visit, he signed a deal for China to build a $4.5 billion hydroelectric dam and a series of other projects.

“China and Angola are good brothers and long-lasting strategic partners,” China’s President Xi Jinping said during meetings with Mr. dos Santos at the Chinese capital’s Great Hall of the People.

Now, Angola’s economic links to Beijing illustrate a broader problem across Africa: Nations that tied their fortunes to China find themselves hostage to its economy’s turbulence.

President Xi is straining to arrest an economic slowdown in China, and that is aggravating a painful correction for oil-rich Angola, Beijing’s top African trading partner.

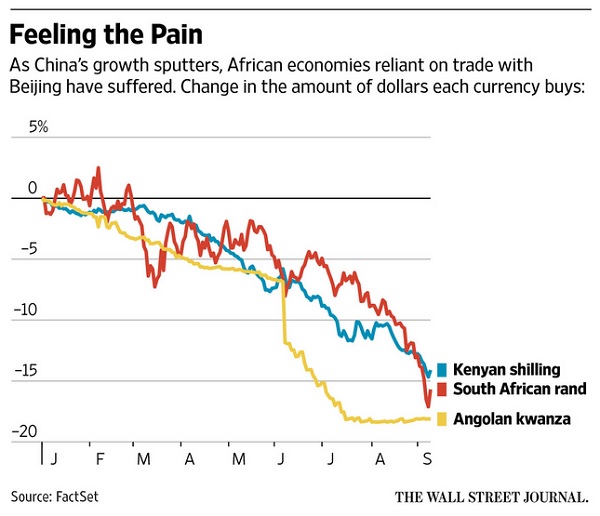

Angolan importers are struggling to pay for critical items like medicine and grain. Moody’s Investors Service last week said rising government debt has put Angola at risk of a rating downgrade. Since January, the country’s kwanza currency has shed a quarter of its value against the U.S. dollar.

“Without the Chinese, there’s no money,” said one Angola-based financier, who said he feared retribution from Mr. dos Santos, whose family controls much of the economy. “The country hasn’t prepared itself by developing in other areas.”

While forging closer economic ties with China, Angola and others also sought to consolidate their political power and aspire to Beijing’s state-led growth model. But those that bet on China’s demand for their oil and iron ore are realizing Beijing might not always be buying – and might not be able to teach them how to hang on to power indefinitely, either.

In Zimbabwe, 91-year-old President Robert Mugabe has declared China’s currency, the yuan, official legal tender along with the U.S. dollar. In the past five years he has secured deals for Beijing to develop roads, telecom networks and farm projects worth some $4 billion.

Last week, in his first state of the nation address in eight years, he took a step back from that partnership.

“Government recognizes the importance of strengthening re-engagement with the international community,” Mr. Mugabe said, in a sharp reversal of the “Look East Policy” – tethering the economy to Beijing as a way to free it from Western meddling – that he had long touted.

In Zambia, Zimbabwe’s neighbor to the north, successive democratic governments have had a love-hate relationship with the Chinese miners tapping the country’s rich copper deposits. As Beijing’s appetite for the metal cools, firms say they may lay off thousands of workers and abandon expansion plans.

“As China rebalances toward a consumer-led growth model, Africa clearly needs to rebalance as well,” said Martyn Davies, managing director for emerging markets and Africa at Deloitte-Frontier Advisory in Johannesburg. “The question is from commodity-driven to what? Anybody thinking that China’s model was transplantable to Africa was naïve to begin with.”

To be sure, China’s vast economic presence on the continent extends beyond commodities trade and its leading role in developing energy and transport infrastructure on behalf of African governments seems to be better shielded from escalating financial troubles at home.

The largest economies in East Africa have less to fear, investors there say, because Chinese contractors are building huge infrastructure projects that look all the more appealing to Beijing.

In Kenya, a $3.8 billion China-led project to build a railway from the port of Mombasa to Nairobi and onward to other East African capitals is going full steam ahead.

Aly Khan Satchu, chief executive of Nairobi-based Rich Management, called it “the Holy Grail of Chinese projects in Africa.”

A state-owned Chinese bank is also funding a light-rail network under construction in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa. “Their investment isn’t affected by the maelstrom in commodities or oil,” Mr. Satchu said.

But such projects are a big strain on the finances of relatively isolated African economies confronting waning risk appetite among global investors. If the bill for Chinese-built construction projects balloons drastically, countries like Kenya and Ethiopia could be made more vulnerable by their ties to China.

“Project execution would have to be flawless – an unlikely scenario, even more so if there is a slowdown from China,” said Ahmed Salim, a senior analyst for East Africa with Teneo Intelligence consultancy.

Africa’s largest economies, meanwhile, rely heavily on China’s demand for oil, diamonds and other minerals, so a deeper downturn in the east could take a big bite out of the continent’s economic trajectory overall. “South Africa has this urge to please the Chinese and to see the Chinese developmental model as almost perfect,” said Mzukisi Qobo, a political scientist and former director in South Africa’s trade ministry.

John Ashbourne of Capital Economics expects sub-Saharan Africa to average 3.3% this year, after clocking 5.4% average growth for a decade. “This will be a very difficult year,” he said.

In South Africa, the ruling African National Congress has matched tighter trade ties to China with bold diplomatic overtures. Last October the Dalai Lama canceled a trip to South Africa after failing for a third time to obtain a visa from South African authorities. China has long considered the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader a separatist and has discouraged world leaders from meeting with him.

South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma arrived in Beijing on Wednesday, his second visit to China in less than a year, to attend a parade marking 70 years since the defeat of invading Japanese forces there.

Now, with cracks in the Chinese model widening, South African executives say they are paying the price for betting too heavily on China’s rise. With factories and mines reeling from China’s waning demand, the government said recently that South Africa’s economy contracted 1.3% in the second quarter.

“This caught us with our pants down,” said Vusi Khumalo, president of South Africa’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry.