News

Africa’s currency manipulators haven’t finished reforms yet

Angola and Morocco last month became the latest African nations to loosen long-held currency pegs, following the lead of Nigeria and Egypt as they sought to revive struggling economies. The question is whether they’ve done enough.

The four nations – among Africa’s six biggest economies – have relieved some of the pressure that was causing dire dollar shortages or hindering businesses, but they may all have to make further moves and reforms to fully satisfy investors.

They changed stance for different reasons. For Angola and Nigeria, the continent’s biggest oil producers, the crash in crude prices almost four years ago meant it was a case of when, not if, their hands would be forced. Egypt, a net commodity importer, was hammered by falling tourism and foreign investment amid political upheaval. Morocco was the least vulnerable, but came under more pressure after Egypt’s move.

‘New Paradigm’

One thing they had in common was their increased propensity – much like emerging-market nations as a whole – to tap international capital markets in recent years. That meant they had to take more heed of portfolio investors’ calls for freer currencies, according to Standard Charted Plc.

“This, more than anything else, has brought about a new paradigm,” said Razia Khan, chief Africa economist at Standard Chartered. “There’s a greater imperative to do things in a way that seems more market-friendly. It’s no longer an option to ignore those calls for reform. It took a very long time, but now we’re seeing it.”

None of them have fully-floated their currencies in the style of South Africa, home of the continent’s biggest financial markets. Here’s an explanation of their foreign-exchange regimes and what’s in store for the rest of the year:

Angola

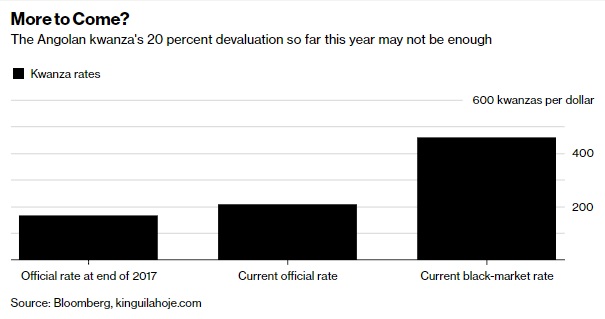

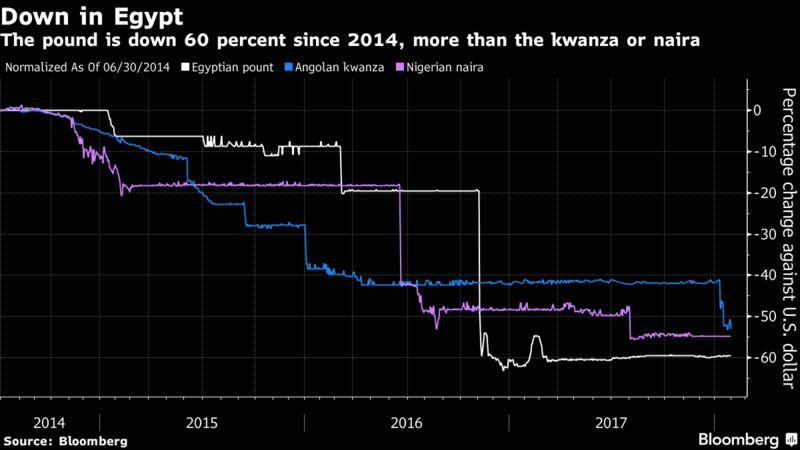

The OPEC member weakened the kwanza about 20 percent against the dollar in January via a series of devaluations, thus ending a peg held since April 2016. That’s gone down well with the International Monetary Fund and should help the country get a bailout from the Washington-based lender as well as tap the Eurobond market. Still, it may have to weaken the currency – which remains difficult to trade for foreigners given tight capital controls – even further to end a scarcity of foreign-exchange.

On the streets of Luanda, the capital, kwanzas trade at 460 for each dollar, making them 55 percent weaker than on the official market, where the rate is 205.5. JPMorgan Chase & Co. analysts think the central bank is targeting a gradual adjustment to 218.

Egypt

The most populous Arab nation has come the closest of the four to a full float following its devaluation of the pound in November 2016, though it retains several controls. The currency’s lost half its value against the dollar since then, which has helped attract foreign flows of $18 billion into T-bills.

The consensus among analysts surveyed by Bloomberg is for the pound to strengthen 1.6 percent to 17.4 against the greenback this year. But Societe Generale SA warned last week those flows are a “double-edged sword” and could reverse if the government slows down its macroeconomic reforms.

Morocco

Morocco was unusual in that its currency strengthened, not weakened, when it loosened its grip by widening a trading band on Jan. 15, allowing the dirham to rise or fall 2.5 percent either side of an official peg, compared with 0.3 percent previously. That was a sign the country, which has benefited from lower commodity prices as it imports grain and oil, had few dollar shortages.

Central bank Governor Abdellatif Jouahri told Bloomberg in an interview last week that a free float may still be five to 15 years away. No matter, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde has described the currency and other economic reforms – designed to turn Morocco into North Africa’s main business hub – as “very promising.”

Nigeria

Africa’s biggest oil producer took the plunge last year when it opened a currency-trading window for foreign investors, effectively devaluing the naira by 12 percent versus the dollar and bringing its total fall since mid-2014 to 55 percent. It also introduced multiple exchange rates, with the official one used for government transactions almost 20 percent stronger than the market one of 360.

Analysts at Bank of America Corp. and Standard Chartered reckon Nigeria can sustain the system for now, thanks to oil prices having risen to around $70 a barrel and strong demand for emerging-market assets. Others, including HSBC, have warned that the complicated currency regime is “keeping long-term investors on the sidelines.”