News

Assessing Regional Integration in Africa VIII: Bringing the Continental Free Trade Area about

The Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) is the first flagship project of the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and a key initiative in the industrialization and economic development of the continent.

It has the potential to boost intra-African trade, stimulate investment and innovation, foster structural transformation, improve food security, enhance economic growth and export diversification, and rationalize the overlapping trade regimes of the main regional economic communities. Fundamentally, the CFTA aims to provide new impetus and dynamism to economic integration in Africa.

While Africa exports mainly commodities to the rest of the world, intra-African trade displays high concentrations of value-added products (and services). It is therefore of particular value to Africa’s development. In recent years, intra-African trade has contributed to 57 per cent of the growth in Africa’s exports of capital goods, 51 per cent of processed food and beverages, 46 per cent of consumer goods, 45 per cent of transport equipment and 44 per cent of processed industrial supplies. The CFTA provides a legal arrangement through which this promising trend can be extended to generate win-win gains for all participating African Union Member States.

After providing a status update of regional integration in Africa, this report considers how to ensure that the potential of the CFTA is fulfilled.

It has long been known that a major challenge in Africa is not a lack of good policies or strategies, but a lack of their effective implementation. Crucial to implementation is an understanding of the political economy underpinning economic integration in Africa. Conceptual issues in this area form the theoretical basis of the report. The insights from this perspective can help to frame the policy choices and institutional arrangements required for effective implementation. The report demonstrates that the CFTA potentially embodies a “win-win” approach to sharing its benefits, so that all countries in Africa benefit and the interests of vulnerable communities are carefully addressed. To this end, the CFTA will require “flanking policies” that governments can use to smooth the impact of the CFTA and a strong focus on achieving tangible outcomes from the Boosting Intra-African Trade Action Plan at national, regional and continental levels. Recommendations are made to assure mutual gains for all countries, irrespective of their current level of development.

These recommendations cannot be fulfilled without strategic investments and financing. The report considers methods of financing for bringing the CFTA about, including the role of domestic resource mobilization, non-traditional financial vehicles and regional Aid-for-Trade. Financing must, however, be buttressed with effective implementing institutions and an appropriate CFTA governance structure. The report emphasizes the need to ensure that CFTA institutional structures are based on practical approaches that work in Africa.

The context of this report is a changing world trade environment in which people’s scepticism of trade agreements has become common. Africans are also frustrated by the lack of progress in the Doha Development Agenda at the World Trade Organization. These shifts call for a renewed vision of the role of trade in Africa’s development trajectory. Bringing the CFTA about is part of that vision, in a way that benefits all African countries and leaves nobody behind, in line with the aspirations of Agenda 2063 and the Sustainable Development Goals. It is also a vision for trade policy coherence in Africa in the changing global environment.

Status of Regional Integration in Africa

Overall integration While Africa has many policy initiatives that express commitments to continental integration, the framework that provides both legitimacy and inspiration is the Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community (the Abuja Treaty), which entered into force in 1994.

According to the Economic Commission for Africa (2016),

The first stage has now been completed, with eight RECs formally recognized by the African Union. These are the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), East African Community (EAC), Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), Southern African Development Community (SADC), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD). The second stage has not been fully completed because progress by the RECs and by members within the RECs has been uneven. The third stage is under way in a number of RECs but not all. Only three of the eight recognized RECs have both a FTA and Customs Union (ECOWAS, EAC and COMESA), although with varying degrees of implementation. While a continental free trade area (CFTA) does not feature explicitly in the AU roadmap, in accordance with the sequential stages of regional economic integration, it is a stepping stone to the creation of a continental Customs Union.

The RECs are progressing at different speeds across the various components of the Abuja Treaty. The EAC has made the most progress across the board.

The following extract from ECA (2016) shows how the CFTA fits into the achievement of the African Economic Community:

The scope of the CFTA Agreement covers trade in goods, trade in services, investment, intellectual property rights and competition policy. This wide scope moves beyond the requirements of a traditional FTA, which requires only the elimination of tariffs and quotas on trade in goods. Therefore, similar to other trading bloc arrangements, it is difficult to neatly place the CFTA under one of the five stages of regional economic integration. The wide coverage of the CFTA is expected to ease the subsequent process of further regional economic integration in Africa.

The harmonization of norms and regulations related to services typically takes place with the establishment of a [single market]. It is however important that trade in services is negotiated alongside trade in goods, since services are inputs into the production of trade in goods and the sector contributes a substantial share to the output of most African economies. The CFTA Agreement will therefore include a sub-agreement on trade in services on the basis of progressive liberalization, consolidating and building on the RECs’ achievements.

Some common investment rules are typically covered under the free movement of capital required by a [single market], whereas an [economic union] would usually contain a fully-fledged common investment policy. Investment issues are rarely covered in free trade areas (FTAs). The CFTA Agreement however is expected to include a sub-agreement on investment that is broad in scope, covering both goods and services. The provision of common rules for state parties in introducing incentives would help to encourage investment into African countries to accelerate development, and would also help to avoid any race to the bottom. A continent-wide dispute settlement system for investment disputes to be settled among state parties will also be key.

Intellectual property and competition policy would typically only be required under an [economic union], the fifth and final stage of regional economic integration. Since few African countries have the institutional capacities and expertise to utilize trade remedy instruments such as anti-dumping, safeguards and countervailing measures, the scope of the CFTA however also covers these areas. Competition policy is a particularly important instrument for regulating unfair trade practices and providing clarity to businesses. Inclusion of a mechanism for regulating competition and facilitating dispute settlement early on will also help to build confidence in the CFTA.

The CFTA Agreement is also expected to include an appendix on the movement of natural persons involved in services and investment, an area of cooperation that is usually not covered until the establishment of a [single market]. This is needed to transform the opportunities provided through the liberalization of trade in goods, services and investment.

Finally, the CFTA project is being rolled out in parallel with the implementation of the Action Plan for Boosting Intra-African Trade (BIAT), which was adopted by the AU Heads of State in January 2012. This initiative goes significantly beyond the requirements of a traditional FTA and is aimed at addressing the constraints and challenges of intra-African trade which are organized under the clusters of trade policy, trade facilitation, productive capacity, trade-related infrastructure, trade finance, trade information and factor market integration. Effective implementation of the BIAT initiative will be crucial to minimizing the challenges and maximizing the gains of tariff liberalization, and ensuring that all African firms and countries are able to take advantage of the CFTA.

In April 2016, the African Development Bank (AfDB), African Union Commission (AUC) and ECA unveiled the Africa Regional Integration Index. The Index seeks to track African countries’ progress in implementing their regional integration commitments to one another in the framework of the RECs. It measures each country’s integration across five dimensions, which have a total of 16 indicators. The following tables capture, for each of the eight AU-recognized RECs, how its members integrate with the rest of the membership, in terms of the country’s overall score and each of its dimensions.

Data updates, not available in AfDB, AUC and ECA (2016), include the most recent data from the African Development Bank’s African Infrastructure Development Index (published in 2016). These data show the average scores for 2011-13 (rather than 2010-12). Work is under way on the second edition of the Index, which will include a sixth dimension on social integration and on gender and will, in addition to measuring within-REC integration, compare how all African countries integrate with the rest of the continent.

Trade integration

Currently there are four functioning free trade areas by AU recognized RECs: COMESA, ECOWAS, EAC and SADC. Further intra-African trade is liberalized through mechanisms beyond the AU-recognized RECs, including the Pan-Arab free trade area, the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). The Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) will liberalize more intra-African trade. This is also the expectation for the CFTA.

Most intra-African trade occurs between African countries that are members of the same regional grouping. For instance, the average country in the EAC sources 86 per cent of its African imports from other EAC countries. For ECOWAS, the comparable figure is 64 per cent, for SADC 90 per cent, and for COMESA 78 per cent.

Though imports are covered by these REC free trade areas, several REC free trade areas exclude certain products. Free trade area utilization rates are also less than 100 per cent: For instance, the ECOWAS Trade Liberalization Scheme is cumbersome for traders, meaning that many still pay tariffs.

EAC countries already have considerable coverage through their EAC single market and the COMESA FTA. Including the TFTA, the EAC countries would on average cover 99 per cent of their intra-African trade. As ECOWAS coverage is much lower, the CFTA would add considerable value. It could also help to solidify free trade in ECOWAS given the reported constraints to traders regarding the ECOWAS Trade Liberalization Scheme.

The TFTA will be especially important for the COMESA countries that are not in the EAC and are not operating the SADC FTA, as well as for several countries that are not yet implementing other REC FTAs, including Angola, Djibouti, Eritrea and Ethiopia. It will also be valuable for Sudan, which has only a small amount of its intra-African trade captured by the Pan-Arab FTA. For the remaining African countries that are not party to an operating REC FTA, the CFTA is expected to contribute to a large amount of intra-African trade liberalization.

These characteristics of intra-African trade are relevant for the CFTA for two reasons: They show that the tariff revenue losses expected of the CFTA are low, because for many countries a large proportion of intra-African trade is already covered through REC FTAs; and the CFTA will help cover intra-African trade for those countries that do not have operating FTAs within their RECs.

They also suggest that the immediate effects of the CFTA – positive and negative – are unlikely to be dramatic in many countries. The CFTA amounts to a step, rather than a leap, forward for African integration, which will help advance all countries to an improved level of trade integration. (The incremental approach can reduce the structural adjustment costs associated with trade liberalization, and still lead to the trade gains, including improved conditions for forming RVCs, permitting better economies of scale, diversifying exports and facilitating the trade growth forecast by numerous trade models.)

Formal trade arrangements

Since the publication of ARIA VII: Innovation, Competitiveness and Regional Integration, Africa’s RECs have made further advances in liberalizing trade.

COMESA

Democratic Republic of the Congo joined the COMESA free trade area in 2016 through an Act of Parliament, taking the total number of countries to 16. The country will reduce tariffs on imports from other COMESA members over a three-year period, with a 40 per cent reduction on duties in 2016 followed by a 30 per cent reduction in 2017 and another 30 per cent in 2018.

EAC

South Sudan has completed its accession to the EAC, having received approval from the EAC Heads of State in March 2016 and having signed the accession treaty in April 2016.

ECOWAS

The ECOWAS customs union, which came into force in January 2015, applies a common external tariff on trade in goods. ECOWAS has also created mechanisms to ensure that their member states implement the common external tariff, including a customs valuation mechanism; regulations to ensure that inputs for the manufacture of zero-rated products do not face tariffs significantly above those placed on the final product; and safeguard, trade, defense and anti-dumping measures.

Ten out of 15 ECOWAS members were implementing the CET by 2016. In 2017, ECOWAS member countries authorized the ECOWAS Commission to coordinate members’ negotiating positions in the discussions for the CFTA.

Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA)

The following developments took place in the negotiations of the TFTA since ARIA VII was written:

-

Eighteen of 26 TFTA member states have signed the Agreement, with a 19th due to sign by 10 June 2017, and one (Egypt) has ratified it.

-

Rules of origin for product types covering more than 60 of the 96 Harmonized System chapters had already been agreed on by end-May 2017.

-

Annexes on trade remedies, dispute settlement and rules of origin have been finalized.

-

The start of the second phase of negotiations has been delayed from its original date.

-

TFTA member states are discussing whether to drop separate TFTA-level negotiations on trade in services and simply to focus on CFTA negotiations on services trade.

Continental Free Trade Area

The CFTA negotiations continued during 2016 and 2017, including the first meeting of technical working groups and discussions on modalities. As shown in ARIA V, and supported by a more recent study by UNCTAD, the CFTA is expected to bring significant economic benefits to Africa via deeper regional integration and higher incomes and GDP.

Progress update: CFTA negotiations and scope

Negotiations for establishing the CFTA were launched in June 2015 by the Heads of State and Government of the AU at the 26th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly in Johannesburg, South Africa. Th AU Assembly decision launching the CFTA urged the participation of all regional economic communities (RECs) and member states and called on the AUC, ECA, AfDB, African Export-Import Bank and other development partners for support, with the aim to operationalize the CFTA by the end of 2017.

Following the launch, six meetings of the CFTA Negotiating Forum were held by July 2017, supported by eight meetings of the Continental Task Force, and two meetings each of the Technical Working Groups, the Committee of Senior Trade Officials, and the African Ministers of Trade. The remainder of 2017 will see these bodies convening frequently, with a further two meetings of the Negotiating Forum.

Free trade agreements can take many forms: Potential CFTA configurations were outlined in ARIA VI. The CFTA negotiations are in progress and so it would be premature to provide a detailed outline of current expectations as to form and content.

On the basis of the draft of the negotiating text, and the negotiations and technical work undertaken, the envisaged scope of the CFTA covers agreements on trade in goods, services, investment, and rules and procedures on dispute settlement. The constituent parts of these agreements and their appendices are expected to cover a range of provisions that aim to facilitate trade; reduce transaction costs; and provide exceptions, flexibilities and safeguards for vulnerable groups and countries in challenging circumstances. It is anticipated that agreements on intellectual property rights and competition policy will be tackled in phase 2 of the CFTA negotiations. Crucially, countries are aligning their interests in a comprehensive agreement that achieves substantially more than tariff reductions and that offers safeguards and flexibilities, which are important for ensuring that the gains from the CFTA are maximized and shared equitably.

Though there remain substantive topics to discuss, the negotiations have achieved considerable momentum and build on a long history of African integration. The CFTA has a notable commitment at the highest policy-making levels. The AU Summit in Kigali in 2017 reaffirmed the commitment of the AU Heads of State and Government to fast track the CFTA. Designing the CFTA at the technical working groups and negotiating forum meetings, and ensuring its effective implementation, are now the critical tasks at hand. As foreseen in the Abuja Treaty, the integration process is to culminate in the African Economic Community.

Intra-African trade in goods

Such benefits are needed, as intra-African exports fell steeply in absolute value from $85 billion in 2014 to $69 billion in 2015. Intra-African trade as a share of the continent’s GDP also declined, from around 3.4 per cent to around 2.9 per cent over the period.

As a share of Africa’s total imports, intra-African imports stood at 14 per cent in 2015. As a share of Africa’s total exports, intra-African exports stood at 18 per cent in 2015.

Intra-REC trade

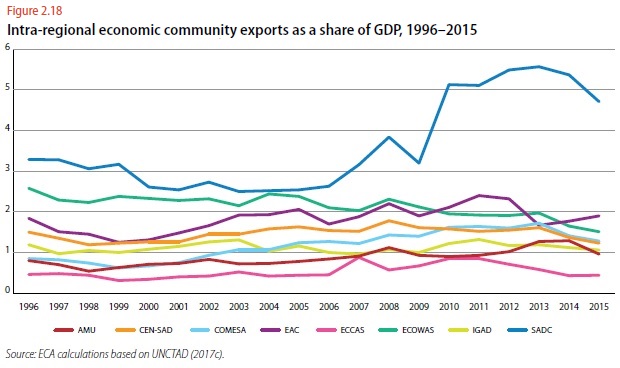

Comparing the share of intra-regional trade in GDP among 25 selected regional trade agreements in force worldwide and reported to the World Trade Organization (WTO), relative to the total GDP of the bloc (since economic blocs with larger GDP may have greater economic diversity within them, creating greater potential gains from trade and therefore a higher share of intra-regional trade in GDP), Africa’s RECs that have regional trade agreements (that is, COMESA, EAC, ECCAS, ECOWAS and SADC), tend to underperform in terms of the share of intra-regional trade in GDP (except for SADC).

Among the eight AU-recognized RECs, SADC consistently has the highest share on this metric, even though it does not have the lowest intraregional economic community average-applied tariffs. Other factors, such as trade complementarity, may explain the pattern of trade within SADC.

Non-tariff barriers and trade facilitation

Africa remains far behind the world on its efficiency of document and border processing requirements for trading across borders, despite significant recent progress. For both document and border processing requirements, the best-performing countries and territories in the global dataset achieved a cost of less than one U.S. dollar and a processing time of one hour or less.

For the TFTA, great effort has been put into eliminating NTBs. A mechanism for reporting, monitoring and eliminating them was developed to address eight categories: government participation in trade and restrictive practices tolerated by governments; customs and administrative entry procedures; technical barriers to trade; sanitary and phyto-sanitary measures; specific limitations; charges on imports; other procedural problems; and transport, clearing and forwarding. As of June 2017, 527 complaints have been resolved and 57 remain active.

On 22 February 2017, the World Trade Organization’s (WTO’s) Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) entered into force. It commits members to taking measures to reduce the cost of international trade by simplifying, modernizing or harmonizing the country’s rules and procedures for exporting or importing. While the Agreement obliges developed countries to implement all measures from the date at which it takes effect, developing and least-developed countries will have longer. Each developing or least-developed country will apply an individual list of measures from countries from the date at which the Agreement takes effect, to be decided by the country in question; these are called “category A” measures. A second individual, nationally determined list of measures (“category B”) will be implemented after a transition period (which can be different from measure to measure), to be decided by the country in question. A third individual, nationally determined list of measures (“category C”) will be implemented by the country after a transition period to be determined by the country (which again can be different from measure to measure) and only once it receives capacity building support to do so. Each developing or least-developed country must notify each measure included in the Agreement in one of these three categories.

As African countries start to implement the TFA, trade is expected to be facilitated and boosted, not only among African WTO members likely to become parties to the Agreement, but also between African countries party to the Agreement and non-party African countries. This is because traders from any country (whether party to the Agreement or not) should be able to benefit when trading with a country that is party to the Agreement from measures taken to simplify or modernize export/import rules and procedures.

As of 20 April 2017, of 44 African WTO members party to the TFA, 19 had ratified it. By the same date, 27 had submitted at least some notifications as to which measures will fall into which categories. However, only five (Chad, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique and Zambia) had already notified for all of the measures under the Agreement.

The African Corridor Management Alliance, which will promote information and experience sharing and joint projects among Africa’s corridor management agencies, was inaugurated in February 2017. This inaugural meeting included discussion of the Alliance’s work plan and related issues. ECA has provided funding and substantive support for start-up activities.

Trade in services

Data on services trade are notoriously weak, with woefully poor coverage on both what is being traded and with whom, and questionable reliability of the meagre data that are available. Moreover, drawing on balance-of-payments data, services trade data essentially ignores investment flows. Notwithstanding improvements in the collection of services trade data over the past 15 years, the macro- and micro- level services data needed for meaningful economic analysis simply do not exist – a challenge exacerbated in Africa.

One technique commonly used for filling (services) trade flow gaps is to make use of “mirror data,” i.e. look at what, for example, the United Kingdom reports as services imports from Ethiopia as a proxy for what services Ethiopia exports to the UK. While helpful to fill certain gaps, the technique is biased towards understanding North-South trade (as it relies on better reporting from countries in the North). But no public bilateral mirror data exist on intra-African services trade flows, so the oft-cited African share of trade with itself (14% of imports or 18% of exports) does not account for services trade in any way. Case study literature (e.g. AUC, 2015) and experience from African services firms strongly suggest that the majority of business for most African micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) is intra-African.

For barriers to services trade – found “behind the border” in the form of regulatory measures – the World Bank’s Services Trade Restrictiveness Index offers a unique snapshot of prevailing discriminatory restrictions in a subset of 27 African countries, sectors and modes. While there is significant diversity among countries, in aggregate the continent scores relatively well relative to high-income Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, with an average overall index score of 33 compared with 19 for the latter. By mode, Africa scores reasonably well, at 31-21 in mode 1, 31-18.6 in mode 3, and 60.7-58.4 in mode 4. This aggregation masks significant diversity at the country and sector levels, notably where African countries maintain fairly restrictive regimes, for example in professional, retail and transport services.

This seemingly good performance contrasts with broader narratives about the restrictiveness of African economies, as well as with anecdotal evidence that suggests that services barriers and regulations in African countries still heavily impede services trade opportunities for firms. Data issues notwithstanding, this highlights the fact that non-discriminatory barriers (which are not captured in the Services Trade Restrictiveness Index) are no doubt significant. As increased trade and integration take place between African services markets, this emphasizes the importance of looking at the role of discriminatory barriers and non-discriminatory regulations in intra-African services trade.

Informal trade

Much trade between African countries is not recorded in official statistics because it is informal. For example, an estimated 20 per cent of Benin’s GDP is based on informal trade with Nigeria alone. However, data on informal trade are, by its very definition, very limited.

The lack of information on informal trade in Africa makes it difficult to evaluate the impact of policies on informal traders and their livelihoods. And while some policies or economic challenges are known to harm informal traders (e.g. cumbersome customs procedures), it can be hard to estimate their economic impact and the importance of changing these policies without accurate data on the extent of informal trade. If these policies are worsening the livelihoods of informal traders, they may also worsen gender exclusion, since women are known to make up 70 per cent of informal cross-border traders. All of this underlines the need to collect and produce better information on informal cross-border trade in Africa, extending to understanding which products and services are being traded informally, and who (men or women) is trading in them.

Economic Partnership Agreements

After negotiating for 12 years, African countries have recently made progress towards signing Economic Partnership Agreements with the EU, though only a handful have started provisionally applying them. Such agreements with Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and SACU have entered into provisional application since the publication of ARIA VII. Kenya and Rwanda have also signed them with the EU since then, but they have not yet entered into provisional application.

This report is a joint publication of the ECA, AUC and AfDB. The report was prepared under the overall guidance of Abdallah Hamdok, ECA Deputy Executive Secretary and Chief Economist, with oversight by Stephen Karingi, Officer-in-Charge, Regional Integration and Trade Division. The core team preparing the Report consisted of David Luke, Coordinator of ECA’s African Trade Policy Centre (ATPC) and Jamie MacLeod, ATPC Trade Policy Fellow.