News

How creating new markets can change the future of development finance

As recently as two decades ago, it was nearly impossible to find a home with a telephone in sub-Saharan Africa. Just one person in a hundred owned a fixed line; for everyone else, the chances of getting one were slim.

Africa is deep into the digital age. Around 750 million Africans have mobile service and access to the lifeline it can provide – linking distant communities, creating jobs, providing basic financial services and real-time crop information. For most people in Africa today, the first phone they ever used was a mobile phone.

How was Africa able to so quickly embrace – and benefit from – the mobile revolution? By mixing smart regulatory reforms that encouraged opening up the telecom sector to competition with private investment. This powerful combination created a new market from scratch and changed lives for the better.

In a world where billions of people lack access to electricity, sanitation or even a simple bank account, the lessons of Africa’s mobile experience are clear. Creating markets generates jobs and sustainable economic growth, builds thriving companies and lifts people out of poverty. This must be at the foundation of development finance, especially in today’s global economic environment.

Without this foundation, official development assistance simply cannot address the massive financing needs facing emerging economies – support needed for infrastructure, tackling climate change, agriculture, small businesses, health, education and employment. Aid alone will not close the $1.5 trillion annual gap in infrastructure investment in developing countries or provide good jobs for Africa and South Asia’s rapidly growing youth population. The solution lies in markets that allow competition to flourish and productivity gains to grow.

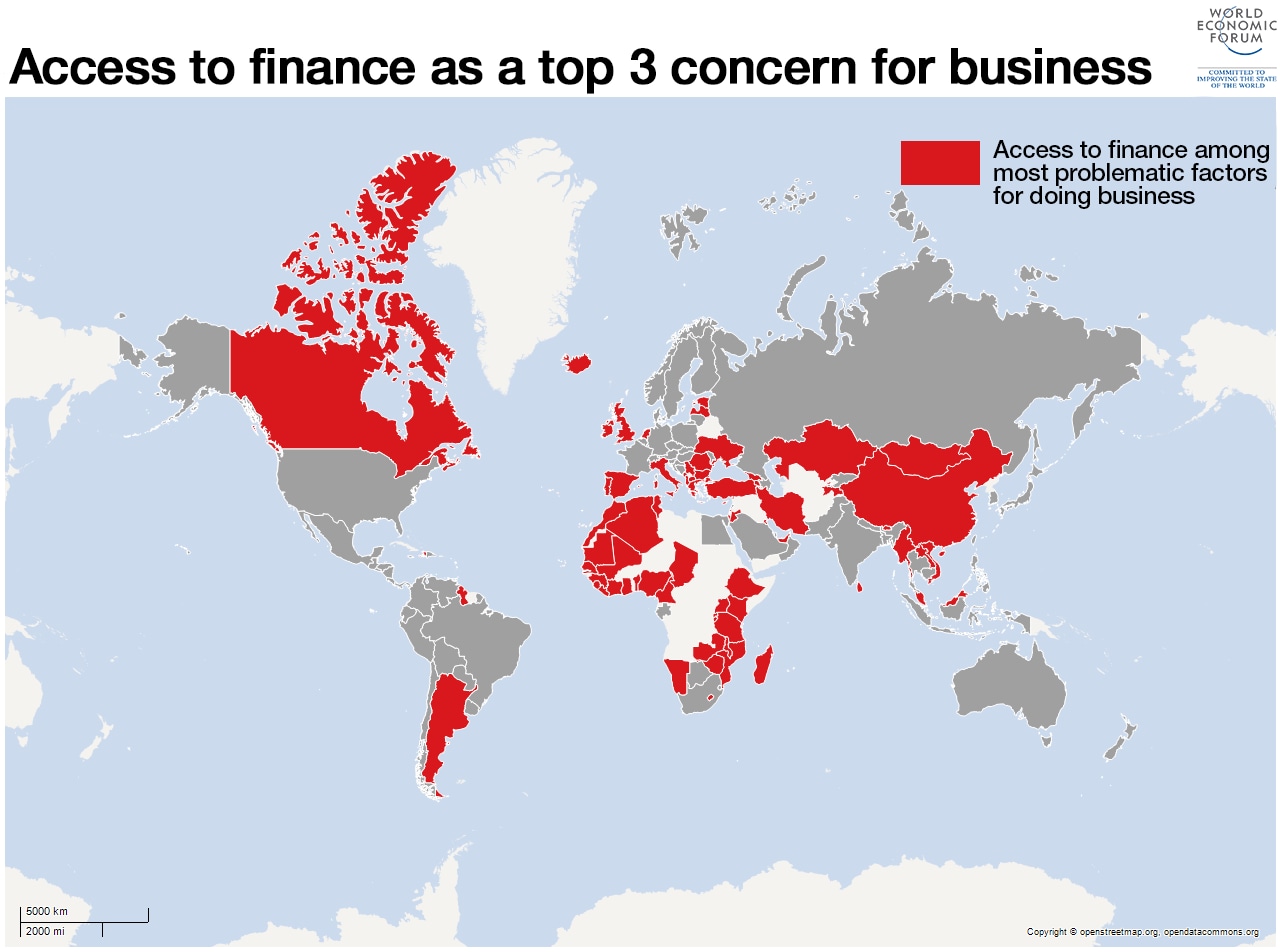

Large pools of private sector capital remain untapped or not channeled where they are needed most. Right now, a big share of the private resources invested in developing countries goes into investments with relatively less risk and does not finance long-term development. In the most fragile environments, private sector involvement is even more limited because markets are non-existent or nascent and regulatory risks are high. Supply chains are fragmented and monopolies hamper critical sectors, like power and transport. Underdeveloped capital markets, meanwhile, are unable to efficiently connect savings to investment.

Development institutions are designing new tools to address these shortcomings and make creating markets a priority. In December 2016, a coalition of developed and developing countries pledged $75 billion in financing over the next three years to the International Development Association (IDA), the World Bank Group’s fund for the poorest nations. This is a clear recognition from donors of the growing role that private enterprise must play in fighting poverty in the world’s poorest and most conflict-affected countries.

The market-creation toolbox now includes a $2.5 billion “private sector window” in IDA designed to tackle fundamental constraints, such as the high counterparty risks of large infrastructure projects and the limited availability of local currency loans. This tool will bring new solutions for dealing with high risk to projects that can have a big impact, but are currently commercially marginal. A separate ”creating markets advisory window”, financed out of IFC profits, will address the rising demand for advisory services and capacity building in the poor and fragile areas.

The drive to create new markets will also require new guarantee instruments and a sharp focus on programmes that can be scaled for maximum impact. The World Bank Group’s Scaling Solar is one example. Through simplified government processes and low pricing, it allows governments to procure privately-funded solar power stations quickly, transparently, and at the lowest tariffs possible. The programme’s first auction, in Zambia in 2016, resulted in the lowest-priced solar power to date in Africa, just above six cents per kilowatt hour. A country where only one fifth of the population has access to electricity will now have a new source of affordable, renewable energy, without subsidies and hence without public outlays.

The focus on creating markets requires a new mindset, one that recognizes the trade-offs between public and private solutions. In addressing the toughest challenges, development institutions should first ask themselves if private solutions are viable. If they are not, the solution should prioritize regulatory reform, upstream project development or blended – public and private – finance. Only when all of these possibilities are exhausted, should we seek to use the limited sources of public finance.

This kind of thinking has worked before. Take Turkey’s energy sector: over the past 15 years, consistent reform has led to market liberalization, billions in private sector investment and, finally, a fully competitive market.

It’s time to take a fresh look at how the world should confront its toughest development challenges. In conversations from Washington to London to Nairobi, there’s a growing recognition that markets – building them and helping them thrive – are essential to a world free of poverty. Using the tools now at our disposal and designing more creative new ones will help get us there.

Philippe Le Houérou is Executive Vice-President and CEO, International Finance Corporation. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.