Blog

Economic Growth and the Environment – Is Green Growth Possible?

The idea that we need to decouple economic growth and resource use is promoted by a number of high-level policies, including the European Green Deal and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). But is it possible?

The debate is ongoing, dating back to long before climate change was on the international agenda. In 1972 the Club of Rome commissioned a report titled ‘The Limits to Growth’. The MIT team commissioned for the report used a computer simulation to model continued economic and population growth in a system with finite resources. The report’s conclusion had Malthusian undertones, predicting that unchecked economic growth would push us to the limits of non-renewable resource depletion, food production and pollution, resulting in a systemic collapse within the following century. Critics of the report argued that the model it used did not consider how resource depletion and pollution could be controlled. They held that changes in the composition of output, substitutions between factor inputs, and technological progress would allow economic growth to outpace the growth of resource use and pollution, thereby expanding the limits indefinitely[1].

The resulting Club of Rome debate separated what Lecomber (1975) refers to as the ‘resource optimists’ from the ‘resource pessimists’. The optimists put faith in human ingenuity to overcome any environmental problem that might arise; the pessimists urge us to diverge from business as usual, stressing that these environmental problems will likely be intractable. The resource optimists and pessimists still exist, but their theories have new names.

The optimists now promote what is frequently referred to as ‘green growth’ – the idea that through the absolute decoupling[2] of economic growth from resource use and environmental impact, continued economic expansion can be compatible with a healthy planetary environment. This can happen through a number of processes: one is the ‘composition effect’. When economies develop, the output mix typically changes due to structural transformation in what the economy produces. Pollution intensive primary and secondary sector activities are replaced by greener services, allowing environmental impacts to decline while the economy grows. Another process is the ‘abatement effect’. When incomes rise, education improves, people become more aware of the need for pollution abatement, and more can be invested in technological advances. Overall this creates an environmental improvement in the state of technology. These improvements allow us to produce more while doing less damage through changes to (a) the economy’s resource efficiency in terms of using less, ceteris paribus, of the polluting inputs per unit of output and (b) emissions-specific changes in processes that result in less pollutant being emitted per unit of input. Green growth proponents suggest that with the right regulations and incentives, technologisation and tertiarisation will mean that continued global economic expansion is compatible with and conducive to environmental protection[3].

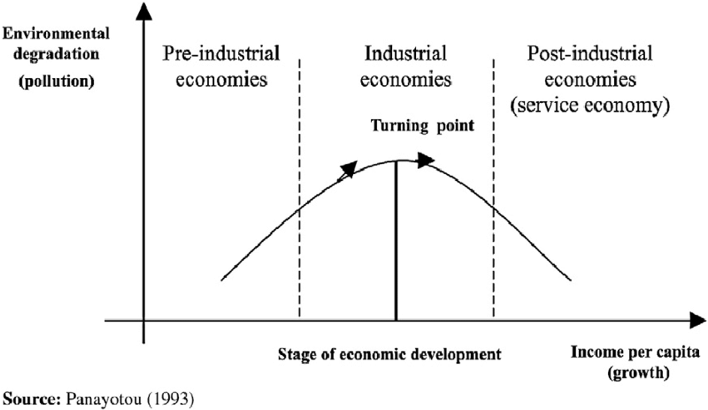

This argument may sound familiar; it’s the same reasoning that researchers have used to explain the Environmental Kuznets curve (EKC), which has been investigated for the last three decades. The EKC is a controversial hypothesis on the relationship between various indicators of environmental degradation (carbon emissions, SO2 emissions, energy use etc.) and income per capita. The relationship is represented by an inverted U-shape curve; the shape implies that during the early stages of economic growth, environmental degradation increases, but beyond some level of income per capita, the trend reverses so that at high-income levels, economic growth leads to reduced environmental degradation[4]. The rising section of the curve is explained by the ‘scale effect’ – in the initial phase of development, as a country builds an industrial base, it grows rapidly, and the effect of this growth, combined with the development of more pollution-intensive industries causes environmental degradation to rise. When the turning point is reached, the composition and abatement effects start to dominate the scale effect, and environmental degradation falls[5].

The Environmental Kuznets Curve[6]

The EKC concept was introduced by Grossman and Krueger in 1991 and popularised by the 1992 World Development Report, which argued that: “The view that greater economic activity inevitably hurts the environment is based on static assumptions about technology, tastes, and environmental investments”. Since then, many empirical studies have investigated whether an EKC actually exists. The findings are highly dependent on what measure of environmental degradation the study uses: a significant share of early studies found that an EKC exists between income per capita and measures of ambient air quality. However, there is much less support from EKC studies that look at carbon emissions where the relationship with income per capita is predominantly found to be strictly monotonic (an increasing curve).

Some cast doubt on the findings of EKC studies, arguing that although the EKC is an empirical phenomenon, most estimates of EKC models are not statistically robust[7]. Others make a theoretical critique of the EKC theory, pointing to the role of trade and the distribution of polluting industries. Such critics point to the ‘pollution haven hypothesis’, arguing that as a country develops and implements more stringent environmental regulations, foreign direct investment flows to countries with weaker environmental standards. As a result, pollution-intensive activities are outsourced to less developed countries, making the EKC trend look more pronounced than it is. Once the less developed economies of today develop, they will be unable to find other countries from which to source resource-intensive products. Unable to outsource, they will face the more difficult and costly challenge of abating these activities. Thus, the critique goes, even if an EKC exists for a particular country, it is not a desirable trajectory from an environmental standpoint, as it may just be a representation of carbon leakage driven by investment location decisions.

Empirical evidence on the pollution haven hypothesis is mixed. Still, the possibility that it is true means that a proper examination of the relationship between economic growth and environmental harm has to factor in the environmental impact of a country’s trade flows. A measure called ‘material footprint’ has been created for this purpose; it measures the total resource impact of consumption by a given nation. A study of the OECD and EU-27 finds that material footprint has been rising at a rate equal to or greater than GDP, suggesting that no decoupling has occurred[8].

Green growth proponents argue that this will change in the future with enough technological innovation and the correct market-based mechanism to support it. A substantial literature has emerged assessing whether this is possible on a global scale. These studies model various ‘high-efficiency scenarios’ where changes like a global carbon price, technological innovations that improve material efficiency, and slowed population growth have occurred. They compare these future high-efficiency scenarios to baseline scenarios extrapolated from existing trends. Even under high-efficiency scenarios with highly optimistic assumptions[9], none of these studies shows that global absolute decoupling is attainable at a rate sufficient to avoid ecological overshoot[10].

It’s possible that their assumptions about the future rates of technological change and resource efficiency are not optimistic enough. As Lecomber (1975) points out, “The central feature of technical advance is indeed its uncertainty”. Thus, one cannot definitively say that green growth and absolute decoupling are impossible. Adopting new methods of production could change the nature of growth. This could include incorporating more circular economy principles into the economy; this would involve designing products for durability, reuse and recyclability to create zero-waste value chains. Redesigning our linear production systems to be more circular could theoretically allow for increases in productivity that do not require proportionate increases in material demand.

Some more extreme resource pessimists argue that even a circular economy is not enough and that the only kind of growth that we can pursue to avoid a climate crisis is ‘degrowth’. Degrowth calls for affluent countries of the global north to abandon their economic growth imperative. This requires restructuring societies and the economies to slow down their ‘social metabolism’ (how rapidly a society consumes resources, generating waste and pollutants). To achieve this, degrowth theorists, notably Jason Hickel, have come up with a number of measures. Firstly, parts of the economy that are ecologically destructive and less socially necessary, such as the production of SUVs, arms, beef, private transportation, should be downscaled. At the same time, universal public goods and services such as healthcare and education should be expanded and de-commodified. This will lead to a reduction in aggregate economic activity and thus a rise in unemployment rates; however this can be remedied by policies such as a shortened work week and a redistribution of the remaining work. This new approach to work will give everyone access to the livelihood and leisure that they need for human flourishing. Wealth redistribution will also play a pivotal role and can be achieved by policies like progressive taxation and a living wage, relieving the pressure to grow the economy in attempts to uplift the poor[11].

A common critique of degrowth is that these changes are not politically feasible and that the theory does not provide a clear plan for how the shift from a growth to degrowth paradigm could occur[12]. As the degrowth paradigm is still in its infancy, it's yet to develop the kind of solid theoretical and empirical foundation that would make it a serious policy option. However, without strong evidence that green growth is an environmentally safe option, the degrowth paradigm should not be overlooked. At the very least, it calls on us to rethink and reframe societal notions of progress in broader terms than consumption. Abandoning GDP as the primary measure of progress, a call that has come from a growing number of welfare economists, would be a good first step.

[1] Lecomber, R. 1975. Economic Growth Versus the Environment. London: Macmillan.

[2] Absolute decoupling occurs when GDP is able to increase while environmental impacts are decreased in absolute terms. This differs from relative decoupling, where environmental harm may be increasing but at a slower rate than the growth of GDP. Hickel and Kallis (2020) show that absolute decoupling, and not relative decoupling, must be the measure of whether green growth is possible. This is because global environmental harm must be reduced in absolute terms if we are to avoid ecological overshoot.

[3] Hickel, J. & Kallis, G. 2019. Is Green Growth Possible?. New Political Economy, 25(4), 1-18.

[4] Stern, D. I. (2018). The Environmental Kuznets Curve. Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.09278-2

[5] Grossman, G. M., & Krueger, A. B. (1995). Economic Growth and the Environment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(2), 353–377. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118443

[6] Panayotou T. (1993). Empirical tests and policy analysis of environmental degradation at different stages of economic development. ILO Working Papers. Available at https://ideas.repec.org/p/ilo/ilowps/992927783402676.html

[7] Stern, David I. (2015). The Environmental Kuznets Curve after 25 Years. Crawford School of Public Policy CCEP Working Paper 1514. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2737634 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2737634

[8] Wiedmann, T.O., et al. (2015). The material footprint of nations. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 112(20), 6271–6276.

[9] Some studies model a global carbon tax that is far higher than any current domestic carbon tax. They also assume material efficiency gains that do not have an empirical basis.

[10] Hickel, J. & Kallis, G. (2019). Is Green Growth Possible? New Political Economy, 25(4), 1-18.

[11] Hickel, J. (2020). What does degrowth mean? A few points of clarification. Globalizations. 18, (1), 1-7.

[12] Herath, A. (2016). “Degrowth”; a literature review and a critical analysis. International Journal of Accounting & Business Finance, 1(1), 44-55.

About the Author(s)

Leave a comment

The Trade Law Centre (tralac) encourages relevant, topic-related discussion and intelligent debate. By posting comments on our website, you’ll be contributing to ongoing conversations about important trade-related issues for African countries. Before submitting your comment, please take note of our comments policy.

Read more...