Blog

How Should the Covid-19 Pandemic Inform Economic and Trade Policy?

The Covid-19 pandemic has had significant impacts on economic activity globally. The World Trade Organization estimated in April that world trade would fall by between 13 and 32% in 2020, with the effects continuing into succeeding years[1]. The wide range of the potential impact on economic activity and trade depends on the responses of the business and government sectors to the pandemic. When lives are at stake, policy makers tend to be conservative, yet lives are at stake not just from the perspective of those infected with the virus but also from those whose livelihoods are being impacted from the effects of the virus on economic activity.

Economists use an indicator termed ‘welfare’ to weigh alternative policy options in response to a shock (such as a pandemic or a global financial event) or as an initiated policy move (such as the scrapping of import surcharges). Welfare in this sense is an indicator of the aggregate well-being of society, something akin to the ‘quality of life’, which although it is a non-financial concept, in economics is given a monetary valuation. This is because it is valued using prices and quantities of the bundle of goods consumed by a representative citizen. For this reason, when a shock occurs or a policy is initiated and it impacts on the consumption bundle of the representative citizen, a welfare change occurs. This change can be positive or negative, with a positive change obviously being desirable and a negative change undesirable.

The net change in welfare is the result of many smaller changes in welfare, some of which are positive and some of which are negative. But the direction of the change in net welfare – the sum of all of the individual changes – indicates either the success of the initiated policy change or the impact of the exogenous shock that occurred (such as a pandemic).

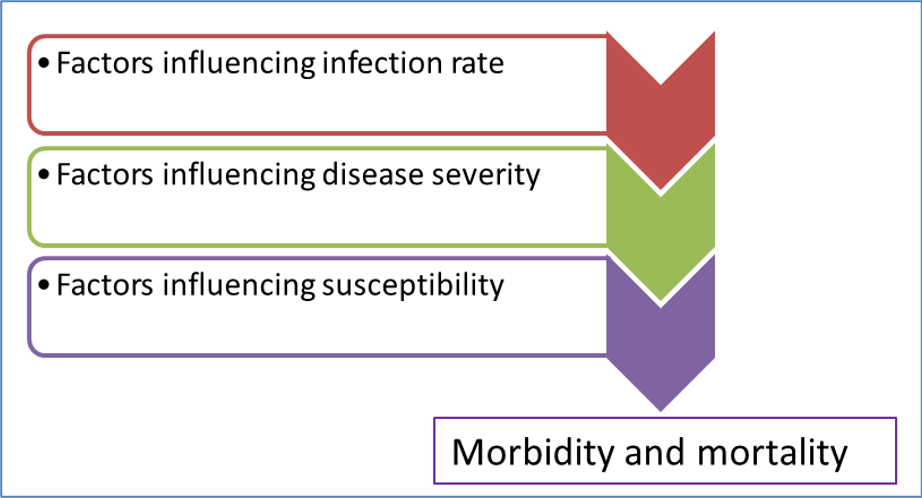

The impact of the pandemic is clearly negative to welfare, firstly because it results in morbidity (sickness) and mortality (death). However, its impact is also negative to welfare given that it has a constraining effect on economic activity and therefore reduces consumption. This clearly requires a policy response from government, to the extent that it is able to. The first path of response from government relates to the health function. The health authorities need to gather data to determine the expected morbidity and mortality of the virus. This process is depicted below in Figure 1. Health researchers gather data on the rate of infection, the extent of the severity of the disease - the severity of morbidity and mortality – and the extent of susceptibility – identifying which demographic cross sections are more susceptible, such as the young, the elderly or those with pre-existing conditions.

Figure 1: Determining morbidity and mortality

A policy response that is based on the health data only would require a strong response in terms of minimising the rate of infection and protecting those who are especially vulnerable to the virus. In addition, the extent of severity would need to be taken into account in forming the appropriate response. A complete lockdown, i.e. the prevention of all social contact, would effectively halt the virus in its tracks. However, as it has been pointed out, morbidity and mortality are just part of the set of determinants of the change in welfare as a result of the pandemic.

Instead, public policy should be informed by the full set of determinants of welfare. The ‘root’ determinant is economic activity, which if all social contact is ended, would grind to a halt. This would be effective in stopping the pandemic, but it would lead to significant welfare losses due to the business failures and unemployment that would result. There are of course, a range of options for lockdowns/business activity restrictions besides the most drastic form, which is the prohibition of all economic activity besides essential services[2]. However if the mortality rate is chosen as the primary focus variable, severe lockdowns are the most effective policy tool.

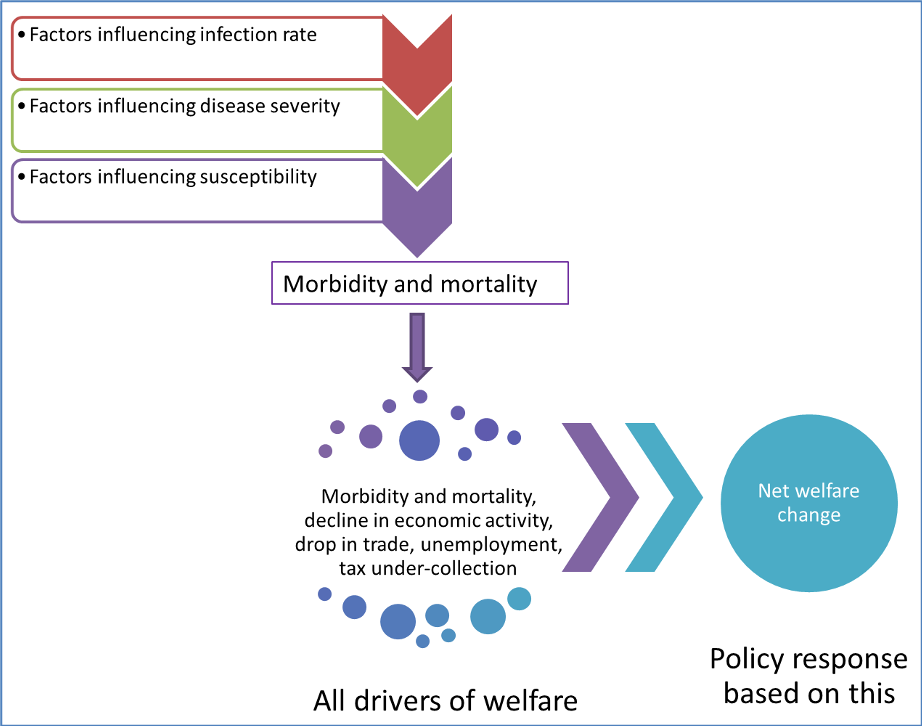

Therefore, public policy cannot afford to only focus on minimising direct morbidity and mortality as a result of the virus; it should instead focus on minimising welfare losses. Another way to say this is that public policy should always seek to maximise net welfare.

How is this achieved? Figure 2 below shows a more complete flow of reasoning on the way to formulating a policy response.

Figure 2: Determining the appropriate policy response

As is evident from the figure, morbidity and mortality data from the pandemic is fed into a model that contains other variables also impacting net welfare. The range of policy responses to the pandemic should then be weighed taking into account not just their impact on the spread of the virus, but also their impact on the change in net welfare.

Some of the initial policy responses have been as follows (in rough order of the severity of the impact to economic activity):

-

Lockdowns: where there is a continuum of options ranging from ‘complete’ lockdown where only essential services can operate as normal; to minimal lockdowns where the list of businesses that cannot operate is explicitly defined rather than the list of those that can. Those businesses, mostly service-based, where social interaction is most intense are the last businesses to reopen. Examples are personal care services, restaurants, venue-based entertainment and leisure travel

-

Border closures

-

Travel restrictions

-

Social distancing

While lockdowns primarily impact domestic economic activity, border closures and travel restrictions impact cross border goods and services trade. Of course, anything that constrains domestic demand will also lead to a drop in import demand and that will constrain global trade as well. These measures greatly limit the ability of businesses to function and some will close down while others may take years to generate disposable income again.

Economies are organic in the sense that industries and sectors are interlinked in very complex ways. Economic growth is generally not linear, and nor is negative economic growth. A destructive economic cycle is the opposite of a ‘virtuous cycle’ in that once firms start failing, a domino effect results and the rate of deterioration is greater than linear. This can lead to severe hardship and a long recovery, as was seen following the 1929 global stock market crash. The recovery took years and arguably was only shortened by the industrial preparations for the Second World War.

How then should policy makers respond to the current Covid-19 crisis? Policy should take into account the full set of drivers of net welfare change, rather than focusing only on morbidity and mortality due to the virus. This could lead to a moderated response to lockdowns, border closures and travel restrictions. Several months into the pandemic, we now have good data on the virus severity, virus infectiousness and the groups that are susceptible to the virus. A more nuanced and focused policy response is now required, no longer the blunt instruments of lockdowns and border closures, but rather policies aimed at supporting business activity, investment and trade. For example, governments should make it explicit in the public realm what the most vulnerable groups are and require these groups to self-isolate[3], while allowing the balance of society to resume activity, albeit with appropriate social distancing and sanitising.

The same ‘exception not the rule’ approach should be used with regard to the set of businesses – those that are based around social interaction – not allowed to operate or only allowed to operate within explicit parameters. This will allow for borders to open, business travel to resume and for investment and trade to resume. It is not too late to take action to prevent further economic carnage, but governments must act quickly and decisively.

[1] Refer to https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/pr855_e.htm. Accessed on 25/06/2020.

[2] For example, Sweden decided against a lockdown and instead only implemented measures on sanitising and social distancing. They have had more mortalities per 100 thousand of the population than most other European countries (besides the UK and France), however at this point in time their mortality rate is not comparable with neighbouring countries that implemented lockdowns, because it is not known where on the disease progression curve they are located relative to the other countries. They are almost certainly further progressed than their lockdown-maintaining neighbours, meaning that their eventual mortality rate may be less severe than their neighbours’. What can be said is that their economy has certainly experienced less disruption – not only in terms of direct economic activity but also in sectors such as education, where schools and colleges have not been closed.

[3] Data from Italy, a country initially severely impacted by Covid-19, shows that the virus is very specific in its impact on people with a certain set of co-morbidities. People without these co-morbidities are far less likely to develop severe disease or die.

About the Author(s)

Leave a comment

The Trade Law Centre (tralac) encourages relevant, topic-related discussion and intelligent debate. By posting comments on our website, you’ll be contributing to ongoing conversations about important trade-related issues for African countries. Before submitting your comment, please take note of our comments policy.

Read more...