Blog

Cooperation on financial services regulation under the AfCFTA

As part of the negotiations on services under the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement, parties will negotiate regulatory cooperation frameworks in priority sectors.

What is regulatory cooperation in financial services?

Cooperation is a broad term referring to the interaction between the regulation and regulators in different countries to achieve regulatory policy outcomes. Cooperation spans from information sharing, all the way to harmonisation.

For example, the OECD’s taxonomy of regulatory cooperation includes dialogue, information exchange, partnerships, recognition, networks negotiated agreements, joint rule-making and integration and harmonisation through supra-national authorities.

Regulatory cooperation to contribute to the goals of the AfCFTA

In the context of trade-in-services, the regulatory treatment of the services can be more important than the formal market access and national treatment commitments found in services schedules (which themselves often also relate to the regulatory treatment of certain businesses). The regulatory requirements, particularly for financial services providers, are usually high and can vary significantly from country to country. Most countries do not restrict or have regulatory jurisdiction over consumption of financial services abroad (mode 2 – e.g. a resident of Ethiopia makes a deposit in a bank in Kenya whilst in Nairobi – although Kenya may restrict this) Mode 1 (cross-border supply) is often highly restricted – countries typically do not allow financial services to be sold from abroad to residents in their countries, but this will usually be reflected in services schedules – for example, South Africa lists all financial services as unbound for mode 1. Mode 4 (presence of natural persons) is often restricted horizontally – individuals will only be able to do business in a country if they are otherwise allowed in (often aligning with migration regulation. Nevertheless, once individuals are allowed to enter to do business, the licensing and registration requirements may provide an additional barrier to their doing business as usually financial services providers need to be licensed or registered. Mode 3 (commercial presence) is the most liberalised mode for financial services – and while this sometimes has restrictions in schedules, such as equity levels or local incorporation, the majority of the barriers are the regulations for the financial service provider operating in the country, such as capital requirements, reporting requirements, conduct rules and others. These are not discriminatory but still create a high barrier to entry for foreign financial services providers, discouraging their participation in new markets and therefore reducing competition in any given market. Foreign services providers also add complexity to the role of regulators and supervisors, who need to understand and analyse businesses in other jurisdictions, may not have access to all information they need and may not have regulatory jurisdiction over all parts of the business. Nevertheless, foreign entrants can be important to meet financial sector policy and regulatory goals, like encouraging competition, lowering prices, making new kinds of financial services available and improving access to financial services.

Given the low level ambition for liberalisation of the services sectors (GATS-plus[1]) these regulatory frameworks are likely to contribute more to making trade in financial services easier between African countries than the liberalisation commitments themselves, which are unlikely to go beyond the existing levels of liberalisation.

Coordination between regulators and integration of regulatory systems – which are both important aspects of cooperation – can address some of the problems that make trade in financial services challenging from the perspective of the service providers, such as two different formats for reporting or conflicting conduct rules and risky from the perspective of the regulatory authorities. Working to improve the experience for the financial services providers, as well as to give comfort to regulators, will create a more conducive environment for the trade of financial services on the continent and thus help countries meet their financial sector goals.

A unilateral rather than cooperative measure, transparency of regulation is also an essential part of improving access for foreign providers and transparency should be mandated as part of the AfCFTA’s regulatory framework. A financial service provider cannot hope to comply with regulations that it cannot identify, or apply for a licence if there is no process for doing so. It is also important that governments are transparent about regulatory changes and consult widely before making such changes. These ‘good regulatory practices’ are increasingly referred to in free trade agreements, and should also feature in the AfCFTA’s financial services regulatory framework. Making these provisions enforceable – by making firm commitments – will ensure that the measures do in fact increase access.

Regulatory cooperation & integration

Coordination is more focused on the supervisory and operational aspects of regulation – regulators coordinate to achieve regulatory outcomes, such as effective supervision and enforcement. Information sharing is at the heart of regulatory coordination, but coordination can also extend to mutual assistance in supervision and enforcement (e.g. Uganda’s authorities need to gather information about a certain Kenyan-based financial service provider and Kenyan authorities actually do the information gathering) as well as joint action (for example a joint taskforce to address a cross-border regulatory problem).[2]

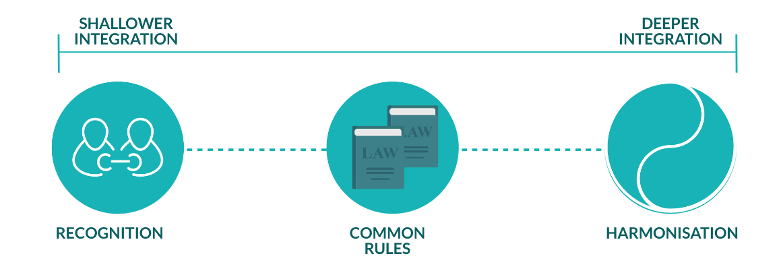

Integration is more about the structural aspects of regulation. Godwin, Ramsay and Sayes (2020) describe it as ‘the process by which certain parts or aspects of one regulatory system are recognised by, or incorporated into, another regulatory system to produce a single, integral system that operates on a cross-border basis.’[3] Harmonisation is the deepest form of regulatory integration and typically not only includes a single set of rules, but also a single supervisory authority. Common rules could be the use of the same rules, but not the same supervision and enforcement. This might be the case, for example, if two countries implement a model law, or an international standard. Both harmonisation and the use of common rules can occur across the board, or in certain subsectors, but common rules are more likely to be found only in certain subsectors. Across the board harmonisation, such as that of the EU, is rare.

The regulatory frameworks created under the AfCFTA should be ambitious when it comes to both coordination and integration but nevertheless should be seen as one of the numerous layers of cooperation between the financial systems across the continent. These include ‘hard’ legal cooperation instruments, such as treaties (including free trade agreements), mutual recognition agreements, memoranda of understanding between regulators and informal arrangements for mutual learning. Although instruments such as free trade agreements are binding legal arrangements between countries, their commitments on regulation are not necessarily binding. This is because often treaties use hortatory language such as ‘shall endeavour’ and ‘will encourage’ – meaning the legal instruments are ‘hard’ but the commitments themselves are ‘soft’. Other layers of cooperation include compliance with standards, global, such as the Basel Core Principles, the International Organisation for Securities Commissions’ Objectives and Principles for Securities Regulation and the International Financial Reporting Standards, as well as regional standards such as those developed by regional cooperation mechanisms, including the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).

The Services Protocol (Article 21) provides that regulatory frameworks are to be developed ‘for each of the sectors, as necessary, taking account of the best practices and acquis from the RECs’. Thus, it is important to note that the RECs have achieved varying levels of both integration and coordination – SACU, as a monetary union shares monetary policy, but not necessarily financial regulatory policy. The West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA) countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo) which are part of ECOWAS operate under a harmonised regulatory framework. This is possible because of the monetary union as well as a regional supervisory body. But ECOWAS more broadly is not as deeply integrated, with, for example separate regulatory bodies in each country of the remaining ECOWAS countries and regulatory restrictions on cross-border participation in markets. The EAC, while not (yet) a monetary union, has achieved relatively deep financial regulatory integration for example, the EAC countries are working towards common banking regulation rules, based on compliance with international standards, including the Basel Banking Core Principles, but regional supervision or licensing is not yet in place.

The mechanisms to be implemented under the AfCFTA are not a substitute or replacement for existing mechanisms, but rather provide a complementary layer to add to the coordination and integration of the financial sector on the continent. In addition, they will provide an important building block to further integration envisaged in the Abuja Treaty. The ultimate goal, for a fully integrated African Community will see harmonised laws and common supervisory authorities right across the financial sector, with the ability for businesses to move seamlessly across African borders. But this vision is a long way off. Some of the monetary unions in Africa already provide pockets of harmonisation, and AfCFTA regulatory framework drafters can learn from these, but at the continental level, more targeted harmonisation and other forms of regulatory cooperation and integration should be prioritised. This will be more manageable than full harmonisation, and will also enable drafters, regulators and policymakers to direct resources and energy to the areas that will have most impact in addressing financial sector (and broader) policy goals. We suggest priority should be given to the following:

Common rules

Digital financial services: New areas of financial regulation should be harmonised, particularly those governing digital financial services such as mobile money, crowdfunding or blockchain based services. Digital financial services are having an important impact on financial inclusion. This is also important digital services tend to be geographically mobile. Often also start-ups, they do not have the resources that incumbent financial providers have to navigate various laws. This should also be more achievable than harmonising existing regulation as these are new areas for regulation.

Financial reporting: While this goes beyond the financial sector, financial reporting standards should be aligned. This is important for providers doing cross-border business – they need only maintain one set of books – and simplify information sharing between regulators.

Consumer protection: Consumer protection across all areas of financial services is a critical policy outcome, and an important part of giving regulators comfort that consumers will be safe when dealing with foreign providers. A common set of rules, that applies cross-border, will achieve this.

Mutual recognition

Financial markets (stock exchanges): Many financial markets across the continent lack depth. Mutual recognition would enable exchanges to open to trading across the continent.

Broker-dealers & financial advisers: Whereby the regulatory authorities recognise the qualification and licensing of these providers in any member state. This would facilitate the recognition across

Securities offerings: Enabling securities to be offered across the continent using a single offer document.

Regulatory cooperation

Pan-African banking: Supervisory colleges should be put in place for pan-African banking institutions. While bank regulation is likely to stay national (or regional in some cases) for the time being, cross-border banking can create risks, particularly in the host country, where in some cases, pan-African banks have systemic importance. Thus, cooperation regulating these entities is essential.

Insurance: Underinsurance is a major concern on the continent, especially for households and small businesses. Insurance regulation and markets are also underdeveloped. Cooperation can help to create more robust regulatory frameworks.

By focusing on priority areas for common sets of rules, mutual recognition, and for regulatory cooperation, regulatory frameworks will be more manageable to achieve, especially given the varying levels in both regulatory capacity and regulatory frameworks. This will also have the most impact on financial sector policy goals.

[1] General Agreement on Trade in Services, under the WTO. GATS-plus suggests that countries will improve on the commitments made under the GATS, but this is not expected to result in new liberalisation as GATS commitments tend to leave a lot of ‘water’ – space between current practice and existing commitments. At best, we could expect to see more countries ‘lock-in’ existing practice.

[2] Godwin, Ramsay & Sayes https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2919161

[3] See note 2 above.

About the Author(s)

Leave a comment

The Trade Law Centre (tralac) encourages relevant, topic-related discussion and intelligent debate. By posting comments on our website, you’ll be contributing to ongoing conversations about important trade-related issues for African countries. Before submitting your comment, please take note of our comments policy.

Read more...