Blog

AGOA Forum 2018 outcomes: where to for a future bilateral trade relationship between the United States and Africa?

Earlier in July 2018 the annual United States – Sub-Saharan Africa Trade and Economic Cooperation Forum (“AGOA Forum”) drew to a conclusion in Washington, D.C. This annual event, alternating between an African country and the United States (the 2019 Forum will take place in Cote d’Ivoire), is mandated by the AGOA legislation and brings together a large number of representatives from the United States and African governments as well as a cross-section of private sector and civil society stakeholders.

AGOA has been around since 2000, originally designed and promoted by Africa’s friends and allies in and outside of Congress; with strong bi-partisan support it was signed into law by then US President Bill Clinton. While originally set to expire in 2008, subsequent renewals – most recently in 2015 – extended the Act through to 2025. As a non-reciprocal preferential trade arrangement it came with some strings attached, but was essentially the United States’ first real effort at establishing a deeper and more meaningful relationship with the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa.

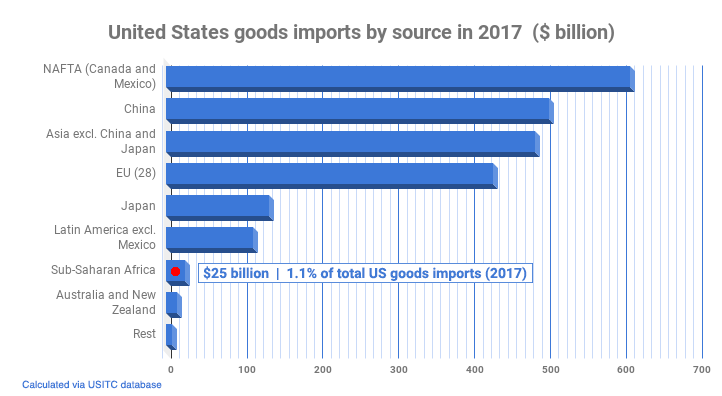

AGOA has arguably been a noteworthy success even if the hoped-for trade and investment relationship between the United States and Africa has perhaps not fully reached the scale and scope originally hoped for. In 2017, US goods imports from Sub-Saharan Africa amounted to $25 billion, or a little under 1.1% of total US goods imports from global sources (this figure has fluctuated significantly over the years, driven by changes in oil imports and oil prices from Africa). US goods imports globally were worth $2.33 trillion in that year.

The political climate of 2000, when AGOA was ‘born’, was significantly different to what it is now. Not only have US presidents and administrations oscillated between Democrat and Republican (for the most part, this nevertheless had relatively little direct impact on the status of AGOA beneficiaries, or on the legislation itself), but changes in the domestic US economy, the general trade environment and a painful global financial crisis in the late 2000s have all left an indelible mark on US attitudes and policy towards non-reciprocal trade arrangements. Increasingly, Congress – or interests within Congress – has used its available leverage either to extract concessions from beneficiary countries, or updated the AGOA legislation in ways that would hold beneficiary countries more accountable in relation to the applicable eligibility requirements. On the face of it, these developments were not necessarily unreasonable, nor unexpected.

While previous iterations of the AGOA legislation sailed through Congress with relative ease, the 2015 (and most recent) 10-year extension and update was held up in the consultative process (the committees in Congress that discuss, fine-tune and synchronise legislation prior to tabling it for a vote on the floor) for many months, not least to get countries such as South Africa more expressly in line with AGOA’s eligibility requirements (the legislation also incorporated a special out of cycle review of South Africa). On reflection, this possibly involved certain cherry picking, for South Africa held some of the greatest potential for Africa-bound US exports and investment on the continent, while also being the largest beneficiary of AGOA. Greater enforcement of AGOA’s eligibility requirement, and changes to the legislation that essentially allows any interested party to submit a petition for an of cycle country eligibility review, resulted in Rwanda earlier this year losing some of its AGOA preferences (for clothing) due to it putting in place barriers to imports of second-hand clothing (from global sources, including the United States).

It was widely understood that the AGOA Extension and Enhancement Act of 2015 was to be the final renewal in its current form. Future trade preferences would by and large need to be based on some form of reciprocity with African countries. This was of course not a surprising development since the very original AGOA legislation in 2000 already noted (at 19 USC 3723) that “Congress declares that free trade agreements should be negotiated, where feasible, with interested countries in sub-Saharan Africa, in order to serve as the catalyst for increasing trade between the United States and sub-Saharan Africa and increasing private sector investment in sub-Saharan Africa…”.

In fact, within three years of the original AGOA legislation, negotiations to establish a Free Trade Area (FTA) with the Southern African Customs Union (SACU – South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia and Swaziland) commenced. The US envisaged that this future FTA would comprise trade in goods, services, non-tariff barriers, intellectual property rights and other disciplines typical of a ‘comprehensive’ FTA; however, there was limited appetite at least amongst the SACU side for an agreement of such scale and scope, and negotiations ultimately deadlocked after a handful of negotiating rounds. Other contributing factors were no doubt a lack of coordinated policy among the SACU parties on many of the disciplines to be included in the agreement, since these were not covered in the SACU Agreement; the 2004 extension of the AGOA legislation by more than ten years to 2015 no doubt removed much of the remaining incentive to conclude an agreement for now.

Fast forward to 2017 and there was renewed vigor on the part of the United States to move to reciprocal agreements. Commerce Secretary under the new Trump administration Wilbur Ross argued that the relationship between America and Africa had to “continue to transition from being aid-based to trade-based…having two-way agreements, not just temporary trade preferences…”. US Trade Representative Rob Lighthizer stated in January of this year that “before very long” the US will “pick out an African country, properly selected, and enter into a free trade deal with that country”.

It is evident that the US administration is pursuing the objective of bilateral trade agreements (for example with African countries), renegotiating existing ones (such as NAFTA) or even withdrawing from those (such as TPP) that in the eyes of the current Administration do not best serve the American people. This appears a much more focused pursuit of commercial opportunity, rather than a more general embrace of global trade and multilateralism, which the current Administration has become skeptical of. The distaste for a more multilateral and regional approach has been evident for some time now. In the African context, the United States is keen to strike deals that prise open markets that are considered lucrative yet perhaps largely restricted or cumbersome to US firms and commercial interests; a particularly sore point in the context of AGOA is the fact that a handful of countries have concluded bilateral agreements with the EU, and how commercial trade relations between Africa and China exceeds what the US has with Africa. But one shouldn’t forget that some of these bilateral agreements with the EU took well over 10 years to conclude and implement, were often fractious if not downright unpopular, and with some commitments particularly on the African side still not yet fully implemented in spite of signed agreements and schedules.

At the 2018 AGOA Forum, Amb. Lighthizer appeared to strongly favour a bilateral approach with (an) individual African country or countries, albeit one that could potentially be expanded to other African participants by means of serving as a blueprint (or possibly other parties acceding later). It is evident that the US is willing to try a new approach (the details of which in terms of scale and scope are unclear), different to the one followed in the failed bilateral FTA negotiations with SACU more than a decade previously. Essentially, the current thinking is to pursue a bilateral agreement with a willing partner, to craft the template agreement so that it can serve as a model agreement for further agreements, and to ensure that this model agreement reinforces regional integration in Africa.[1] This approach clearly also raises the stakes in getting a first agreement “right” but implicitly allocates much of an African negotiating position to (possibly) a single country.

And here an increasing policy divergence was very evident at the AGOA Forum, with the African position favouring at least a regional if not a continental approach to a future, deeper and bilateral relationship with the US. It’s been only a few months since the Extraordinary Summit at which the African Continental FTA was presented for signature, a major milestone in African regional integration. To date 49 African countries have signed while 6 have ratified the agreement (for it to enter into force, 22 countries must ratify the agreement), in what aims to be a massive continental trade zone with free trade in at least 90% of goods after fifteen years.

The official outcome and communiqué by the African trade ministers (African Ministerial Consultative Group on AGOA) following their deliberations was not particularly direct on this issue though, addressing inter alia technical and capacity issues and recommending a review of a possible post-2025 trade partnership with the US, a reflection on the trade impact after AGOA and so forth, while cautioning about the need to preserve policy space and promoting continental industrialization. The ensuing discussions at the Ministerial Forum, with inputs by the trade ministers of a number of African countries, were however much more forceful in placing the AfCFTA and regional integration processes at the center of the discussion around a future arrangement.

There was thus little evidence of a common vision, between the US on the one hand, and African representatives on the other, around this very fundamental point. Despite a broad African insistence on a regional or continental approach, Amb. Lighthizer insisted that there are in fact individual countries that would like to engage bilaterally, and to pursue such an agreement with the US. “Call my office” was his invitation to African delegates. It is being suggested, according to some reports, that Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya and Ghana were being considered for a model trade agreement. In contrast, South Africa’s trade minister Rob Davies has stated that the country was not interested in pursuing a country-level bilateral agreement (favouring the regional/continental approach). Of course, SACU member states also have to negotiate agreements of this nature together as a bloc.

In fairness, AGOA in its current form has 7 years to run, and while it is plausible that there will be a post-AGOA arrangement it is very unlikely to take on the form of present-day AGOA, nor that it would readily include countries above a certain development or income threshold or those where the US has a particular commercial interest. In other words, it is time to act in developing a post-AGOA relationship that preserves and extends preferences and is of mutual benefit to the parties.

And while a regional or continental approach holds advantages, a measure of realism is necessary: bringing together dozens of African countries with at times vastly different levels of development and economic (and trade) interests, and defensive concerns perhaps, (to be) agreeing common positions on market access, origin rules, services trade commitments, investment and other trade and related disciplines, represents a massive undertaking in terms of technical resources and coordination in particular. One needs to keep in mind that the AfCFTA (once sufficiently ratified and in force) is essentially an FTA – as the name implies – and it is unrealistic to expect its signatories to now adopt common positions required for negotiations with external parties.

Even now, in spite of ambitious timelines and very significant progress in getting this far with the AfCFTA, at least on paper and politically, much work (and likely many years) lie between the present and a future state whereby the ultimate beneficiaries of the AfCFTA will reap its benefits, and where businesses trade across African borders on a preferential basis in the spirit envisaged by the AfCFTA. This may simply be too long to have to wait, at least for those countries with most to lose or gain in the context of US-Africa trade.

An FTA could lock in the benefits of AGOA (or other non-reciprocal arrangements) and more, leading to greater certainty for business, but even this assurance is being shaken with the recent imposition by the US of high unilateral import tariffs on hundreds of steel and aluminium products on the basis of (Section 232) national security considerations, with possible similar action to follow on automotives and other products. Already this issue is being addressed publicly, with South African “interest groups” reportedly planning to sue the US to enforce the country’s “rights” under AGOA (it is unclear on what basis this would be). US trade partners with agreements in place, or long-standing allies in other ways, have not necessarily been spared US steel and aluminium tariffs either. This is also having a direct impact on AGOA trade since many of these tariff lines were duty free under AGOA.

What is important is that Africa takes much more of a proactive lead and real interest in the post-AGOA trade relationship with the US. Focusing primarily on domestic capacity building requests, non-tariff barriers and other (often purely domestic and supply-side) challenges involved in accessing the US market is no longer adequate. At the 2017 AGOA Forum in Togo, African countries agreed to convene an AGOA consultative meeting which is yet to happen.

If at least a regional approach (such as through the respective regional communities) to these negotiations is to be favoured, it is critical that some initial preparatory groundwork, technical and legal analysis, and preferred policy approaches, begin to take shape and fall into place on the African side. In spite of the apparent single-country bilateral approach envisaged by the US, there seems to remain sufficient flexibility and receptiveness to any well-founded approach by Africa, if this can lead to a mutually beneficial outcome within a reasonable and technically feasible timeframe.

[1] See Amb. Lighthizer’s opening remarks at the 2018 AGOA Forum, available at https://www.tralac.org/news/article/13255-2018-agoa-forum-opens-in-washington-dc-statements-by-ustr-robert-lighthizer.html

This Trade Data Update provides an overview of Morocco’s intra-African trade relationships, both within the Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and with other individual African countries; the top import and export products traded; and applicable tariffs.

Data is sourced from the International Trade Centre (ITC) TradeMap database and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) Tariff Database. The update is accompanied by a visual representation of key data and trends in an infographic.

Regional Economic Communities

Morocco is a member of the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), Pan-Arab Free Trade Area (PAFTA) and the Arab-Mediterranean Free Trade Area.

AMU is a Regional Economic Community (REC), whose members are: Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia. AMU Treaty calls for a gradual move towards the free movement of goods but no progress has been made yet and there is no free trade agreement in place in the region.

CEN-SAD is a REC with an ambition is to establish an Economic Union, with free movement of goods and services. The CEN-SAD Treaty focuses on cooperation activities to foster peace, security and sustainable development and measures to adapt to climate change but has not yet entered into force, there is still no free trade agreement in place. CEN-SAD currently has 24 member states.

PAFTA, also called the greater Arab Free Trade Agreement, is a free trade area (FTA) providing for liberalisation of trade in goods originating in and coming directly from 18 Arab countries. The implementation of the FTA was completed in 2005.

The Arab-Mediterranean Free Trade Area provides full liberalisation of trade among Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia and Jordan.

Intra-Africa trade

In 2017, Morocco exported and imported goods to the value of US$2.2 billion and US$1.6 billion, respectively to and from the rest of Africa. Morocco’s intra-Africa exports account for 9% of Morocco’s total exports, and imports for 3% of total imports for 2017.

Morocco’s top export products are mineral and chemical fertilisers, which account for 30% of the total exports to Africa, ahead of prepared or preserved fish (9%), insulated wire cable (4%), frozen fish, cane or beet sugar, cement and motor vehicles (3% each), petroleum oils, and cartons, boxes, cases or bags (2% each) and casks, drums, cans or boxes (1%). These top 10 export products make up 60% of Morocco’s total intra-Africa exports. Morocco’s top 10 export (African) destinations are Ethiopia (importing 11% of the total Morocco intra-Africa exports), Algeria (9%), Mauritania and Senegal (8% each), Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire (7% each), Ghana (5%), Tunisia (4%), Libya and Mali (3% each).

Morocco’s top imports include petroleum gas (accounting for 31% of total intra-African imports), dates, figs, pineapples, avocados, guavas, mangoes and mangosteens (5%), coal, sanitary pads and tampons and coffee (3% each), bran, sharps and other residues, monitors and projectors, residues of starch manufacture, cobalt oxides and hydroxides, and sheets of veneering (2% each). These import products account for 55% of the total intra-African imports. The top 10 source markets of Morocco’s imports are Algeria (accounting for 35% of Morocco’s intra-Africa imports), Egypt (29%), Tunisia (14%), South Africa (6%), Nigeria and DRC (2% each), Uganda, Libya, Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire (1% each).

Intra-Africa import tariffs

Most goods imported into Morocco from the Arab-Mediterranean Free Trade Area member states enter duty free. The only exceptions are live animals, meat and fish products (between chapters 1 and 3). Live animals from the from the Arab-Mediterranean FTA into Morocco face average ad valorem duties between 32.67% and 9.5%, meat and edible meat offal between 8.5% and 1.9%, and fish and crustaceans between 1.9% and 0.02%.

Morocco grants duty free access to 33 African least-developed countries on most products, except for meat and edible offal (facing average ad valorem duties between 41.64% and 32.67%), fish products (facing average ad valorem duties between 20.63% and 5%), nuts, pineapples, guavas and mangoes (facing average ad valorem duties between 3.8% and 0.8%).

Morocco has signed free trade agreements (FTAs) with Egypt, Guinea, Mauritania, Senegal and Tunisia, according tariff preferences for some products. Egyptian products into Morocco enter duty free under the FTA between the countries, except coriander, cumin and juniper seeds (facing average ad valorem duty of 24.9%), salt products (facing average ad valorem duties between 24.9% and 3.24%), ores, slag and ash (facing average ad valorem duties between 3.11% and 0.8%), and mineral fuels (facing average ad valorem duties between 0.7% and 0.2%).

About the Author(s)

Leave a comment

The Trade Law Centre (tralac) encourages relevant, topic-related discussion and intelligent debate. By posting comments on our website, you’ll be contributing to ongoing conversations about important trade-related issues for African countries. Before submitting your comment, please take note of our comments policy.

Read more...