News

Ibrahim Index 2015: ‘Governance progress in Africa is stalling’

How well is your country governed? This is the question the Ibrahim Index of African Governance seeks to answer. This year’s results are bad news for the continent as a whole, and South Africa specifically. But what’s going right in Zimbabwe?

Sudanese billionaire Mo Ibrahim believes most of Africa’s problems are rooted in poor governance, and there are few who would disagree with him. He also believes that governance can and should be measured, accurately and objectively, and that critiques and policy should be based on numbers rather than conjecture. To this end, he created the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG), which is now in its ninth iteration.

The 2015 edition – which includes South Sudan for the first time, as there is now enough data for Africa’s newest country – reveals a continent in governance limbo, with no overall improvement or decline. This headline statistic masks plenty of activity at country and category level, however – some of it surprising. We’ve trawled through the data to find the most interesting trends.

African governance is stagnating

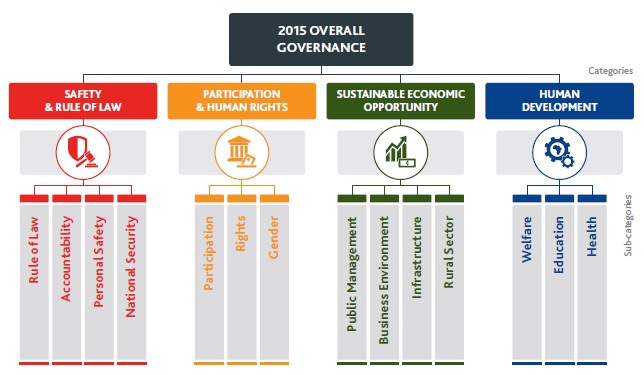

This is the major takeaway from this year’s results. “The results of the 2015 IIAG reveal that overall governance progress in Africa is stalling. Improvements in (index categories) Participation & Human Rights and in Human Development are outweighed by deteriorations in Safety & Rule of Law and Sustainable Economic Opportunity,” said Ibrahim.

Should we be concerned? Absolutely. The Mo Ibrahim Foundation is desperate not to reinforce negative stereotypes of Africa, which makes this a particularly painful admission – there are few stereotypes more prevalent than that of poor African leadership, and this data will prove many an Afro-pessimist’s point.

Which is why Ibrahim is at pains to stress that this overall trend does not tell the whole story. “Africa is not a country. The scores and trends seen in the 54 individual countries on the continent are diverse, each showing specific patterns in their own right, along a wide range of results, with more than a 70-point gap between the top-ranking country, Mauritius, and the bottom-ranking country, Somalia,” he said.

The star performers

Over the last four years, only six countries improved across all four Ibrahim Index categories. These star performers are: Cote D’Ivoire, Morocco, Rwanda, Senegal, Somalia and Zimbabwe. An interesting mix which includes democracies, dictatorships, a monarchy and a conflict zone – in other words, no matter what the ideologues may tell you, there are several different formulas for better governance in Africa.

Côte d'Ivoire deserves a special mention, showing by far the greatest overall improvement. Credit for this must go to President Alassane Ouattara’s government, who have done a decent job of imposing stability following the 2010-2011 political crisis.

What’s going right in Zimbabwe?

It’s hard to ignore Zimbabwe’s presence in the top six improvers. In fact, it has shown the second largest overall governance improvement since 2011 – an uncomfortable statistic for President Robert Mugabe’s many critics, and one which will no doubt be trumpeted on the front page of The Herald come Tuesday morning.

Drill down a little further, and the data is even more puzzling. Zimbabwe’s biggest category-level improvement came in Participation & Human Rights, with strong showings in the sub-categories of Rights and Gender. The country also did well in National Security, Personal Safety, Public Management and Infrastructure, Welfare and Health (it helps, of course, that the country is coming from such a low base).

For the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, results like these are potentially embarrassing, but also demonstrate the utility of the Ibrahim Index: like it or not, some things have improved in Zimbabwe over the last few years, probably as a result of increased political stability, and here are the numbers to prove it.

South Africa papers over the cracks

South Africa is the fourth-best-governed country in Africa, behind only Mauritius, Cape Verde and Botswana. The good news is that we’ve maintained that position for years, and are even showing small signs of overall improvement (up 0.9 points since 2011, although this is well within the margin of error).

But the devil is in the details. Our high ranking conceals some concerning trends at sub-category level, in particular our exceptionally poor performance in Personal Safety and National Security. For its citizens, South Africa is still an unacceptably dangerous country.

More surprising is the deterioration in the Participation & Human Rights category, driven by declines in the Gender and Rights sub-categories. Specific indicators showing significant declines include Freedom of Association & Assembly, Freedom of Expression, and Legislation on Violence Against Women.

While these have yet to affect South Africa’s overall governance performance, it’s clear that these declines are the canaries in the coal mine – and should provide further evidence, if any was needed, that all is not well in the Rainbow Nation.

Banks and customs

Across the Ibrahim Index’s 93 indicators, the two showing the biggest decline over the last four years are Soundness of Banks (-11 points) and Customs Procedures (-9 points). These are both concerning.

Reliable financial institutions are the foundation of any growing economy – if people are losing trust in African banks, then sustainable economic growth is more remote than ever. Efficient customs, meanwhile, is absolutely essential for trade across African borders. The African Union thinks intra-African trade is fundamental to Africa’s economic future, and it’s not a good sign that, despite the continental body’s efforts, customs procedures are getting worse instead of better.

The biggest losers

No surprises that the biggest declines in governance in the last few years come from war zones. South Sudan, the Central African Republic and Mali fare particularly poorly. The lesson here is crushingly obvious, but is worth repeating anyway: conflict remains the biggest impediment to good governance in Africa.

Foreword

The 2015 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) is the 9th iteration since we launched in 2007. The IIAG has been refined and strengthened each year since then under the guidance of the Board of the Foundation, the IIAG Advisory Council, and our friends and partners, to all of whom I wish to extend our thanks and gratitude.

The results of the 2015 IIAG reveal that overall governance progress in Africa is stalling. Improvements in Participation & Human Rights and in Human Development are outweighed by deteriorations in Safety & Rule of Law and Sustainable Economic Opportunity. Over the last four years, only six countries out of 54 were able to achieve progress in all four components of the Index. If we drill down a little further, to sub-category level, gains achieved in Participation, Infrastructure or Health are of course heartening, but the drops registered by National Security, Rural Sector, and, most of all, Business Environment, are cause for concern.

However, Africa is not a country. The scores and trends seen in the 54 individual countries on the continent are diverse, each showing specific patterns in their own right, along a wide range of results, with more than a 70 point gap between the top ranking country, Mauritius, and the bottom ranking country, Somalia. The 2015 IIAG results also point to a shifting landscape. Over the last four years, half of the top ten performing countries have registered a decline of their governance performance. Meanwhile, half of the ten largest improvers over this period include countries which already rank in the upper rungs of the Index, and may well be potential powerhouses.

2015 is a milestone year for Africa. The future African landscape will be defined by the new Sustainable Development Goals, which are meant to guide us for the next 15 years, and the decisions that will come out of COP21. What is crucial is that the complexity of Africa is appreciated within these discussions, that the decisions made are based on data and sound information and that their implementation will be closely monitored according to results.

In that context, my hope is that this Index can be a useful tool.

Key findings of the IIAG 2015 include:

-

The African average score for overall governance in 2014 is 50.1, a slight improvement since 2011 (+0.2). Over the last four years, only half of the top ten governance performers managed to improve their overall governance score, and 21 of the 54 countries have deteriorated.

-

The Sustainable Economic Opportunity category exhibits both the lowest continental average score (43.2) and the largest performance drop since 2011 (-0.7). Sustainable Economic Opportunity includes the most deteriorated sub-category in the IIAG since 2011, Business Environment (-2.5). This sub-category includes the most deteriorated indicator in the IIAG over this time period, Soundness of Banks (-11.0).

-

Among the generally negative trend of the Sustainable Economic Opportunity category, four countries, Morocco (+11.2), Togo (+9.5), Kenya (+5.9) and Democratic Republic of Congo (+5.4), exhibit impressive gains of more than +5.0 points.

-

The overall governance score range between the best regional performer, Southern Africa, and the poorest regional performer, Central Africa, is more than 18.1 points in 2014. This has widened by +1.7 points since 2011.

-

With a 79.9 score for overall governance in 2014, Mauritius stands over 70 points higher than the continent’s weakest governance performer, Somalia, which achieved a score of 8.5.

-

The top three countries, Mauritius, Cabo Verde and Botswana, all exhibit a decline in overall governance and in at least two of the four components over the last four years, calling into question whether these countries will continue to dominate the top of the rankings in future.

-

The bottom three countries in overall governance are Central African Republic (24.9), South Sudan (19.9) and Somalia (8.5). Two of these, South Sudan (-9.6) and Central African Republic (-8.4), have also registered the most extreme deteriorations, along with Mali (-8.1).

-

The top ten improvers in overall governance over the last four years represent almost a quarter of the continent’s population. Five of these countries, Senegal (9th), Kenya (14th), Morocco (16th) Rwanda (11th) and Tunisia (8th), already rank in the top 20 of the IIAG, leading to the question of whether they might become the continent’s next powerhouses.