News

AGOA-IV and the trade prospects of sub-Saharan Africa

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a piece of US domestic legislation first passed by Congress and signed into law in May 2000, was a product of US efforts to reorient US trade policy following the end of the Cold War. Around the same time, the USA had devised a ‘Big Emerging Markets’ strategy aimed at deepening US trade and investment relations with ten fast-growing nations with large and expanding middle classes, ranging from China, India and Brazil to Turkey and Poland (plus newly post-Communist Russia in addition to the ‘Big Ten’).

The strategy involved offering to open US markets to exports from big emerging markets in return for their governments’ commitments to market liberalisation, good governance and democratisation. The longer term US objective was to open these markets to US exports and investments. While South Africa, then newly under majority rule, was on the Big Ten list, the USA needed a broader approach to trade policy with Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). AGOA became the means to extend this emerging markets trade and investment strategy to Africa.

AGOA has since become the centrepiece of US-SSA trade relations and was recently renewed until 30 September 2025. However, notwithstanding AGOA’s significance, bilateral trade between the USA and SSA countries remains limited and concentrated in certain sectors, while overall AGOA exports, most notably oil, have been declining in recent years. Against this backdrop, this issue of Commonwealth Trade Hot Topics provides a brief overview of AGOA’s evolution and AGOA-IV’s main provisions and highlights some of the opportunities and challenges for promoting SSA's trade in the future.

Trade trends under AGOA 2001-2015

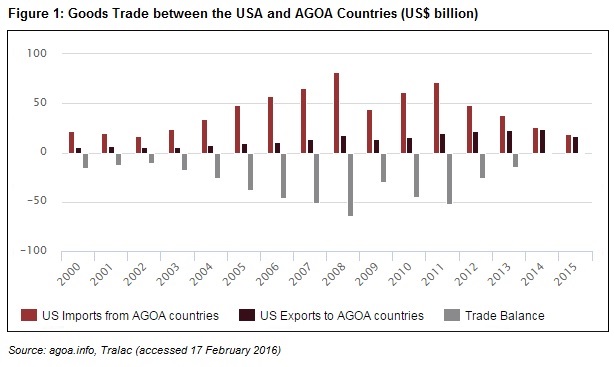

Combined two-way trade between the USA and AGOA-eligible SSA countries has doubled between 2001 and 2014, with a consistent but steadily declining trade surplus for eligible AGOA countries (imports and exports were broadly balanced in 2014 and 2015). As Figure 1 shows, total trade grew steadily from US$28 billion in 2000 to the peak of US$100 billion in 2008, the year before the global financial crisis had its greatest impact on the US economy. By 2011, trade had mostly recovered but has been on a downward trend since then largely due to movements in oil prices and exports of oil products, as discussed later. In 2015, combined two-way goods trade was valued at US$36 billion, compared to $50 billion (2014), $61 billion (2013) and $66 billion (2012). US exports to SSA have grown steadily under AGOA, excepting for the impact of the 2008 financial crisis and the likely effect of the high US dollar exchange rate in 2015.

The overall impact of AGOA upon US imports has been minimal. In 2015 only US$19 billion, slightly under 1 per cent of total US goods imports of US$2.27 trillion, originated in SSA, a bit over half the value of which enter duty-free under AGOA or GSP. AGOA’s impact on SSA’s export performance (especially for non-oil producers) has been somewhat greater, although still only a small number of the countries eligible for AGOA benefits have sufficient domestic productive capacity to export enough to the USA to benefit significantly.

The US effective rate of tariff protection on imports from Africa was already low before AGOA. According to the International Monetary Fund, AGOA has only benefited SSA exports exposed to significant US tariff protection: 5 per cent of total exports, but 23 per cent of total non-oil exports. In 2000, prior to AGOA, only US$4 billion out of US$23 billion in SSA exports to the USA benefited under GSP. The main product additions to GSP duty-free entry under AGOA were petroleum products, apparel, and certain other industrial and agricultural goods. The average US tariff on petroleum imports was only 1.5 per cent. Its removal raised the price received by exporters by 1 per cent, thereby benefiting SSA oil exporters, such as Nigeria, Angola, Chad and Gabon. The average US apparel tariff was 13 per cent, but MFA quotas further restricted exports substantially until 2004. AGOA gives little additional tariff preference to LDCs: close to 90 per cent of products eligible for AGOA benefits were already tariff-free under enhanced GSP if imported from qualified LDCs. Additional potential SSA exports were still not included under AGOA, with 174 tariff lines bearing an average tariff of 2.5 per cent and a further 893 lines bearing an average tariff of 11 per cent.

The three categories of SSA exports under AGOA, namely oil, apparel, and other products, have followed very different, and largely unrelated, trajectories. While all AGOA exports declined following the 2008 global recession, apparel exports have been much more volatile for industry- and market-specific reasons, whereas oil exports first rose and then declined for secular reasons noted below. Other products, exported primarily from South Africa, have shown a secular increase in recent years.

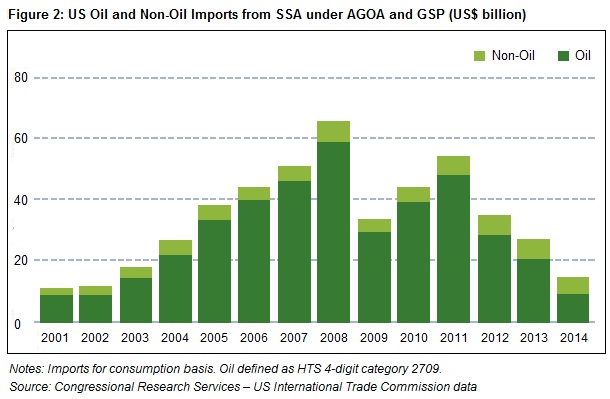

Over the period 2001 to 2014, AGOA non-oil exports increased from US$2.8 billion to US$4.4 billion, representing an increase of US$1.6 billion. However, as Figure 2 highlights, the largest segment of SSA exports to the USA by far under AGOA has been oil, which consistently accounted for a share greater than 90 per cent of total exports under the scheme. However, 2014 is the notable exception, with non-oil AGOA exports as a share of total AGOA exports at its highest ever. This change in volumes of oil imports to the USA under AGOA has been the biggest driver of change in overall volumes of imports under AGOA. In the early years of AGOA, availability of oil imports from African producers such as Nigeria and Angola became particularly important strategically to the USA, as the USA sought to reduce dependence upon oil imports from the Middle East. However, in recent years oil imports to the USA have declined steadily, as domestic sources and alternative fuels have replaced imported oil in US energy markets. Oil import volumes to the USA under AGOA have been volatile. AGOA preferences do not affect the volume of SSA oil exports to the USA significantly, because the US import tariff on oil is so minimal, only 5-10 cents/barrel.

Of the two non-oil categories of AGOA exports, apparel has been considered most significant from a development perspective. Initially SSA apparel exports increased moderately under AGOA, benefiting from AGOA beneficiaries’ exemptions from broad US apparel quotas under the MFA. When the MFA ended in 2004, AGOA beneficiaries lost this advantage, cutting into SSA exports significantly.

AGOA benefits have stimulated and facilitated the development of apparel manufacturing industries significantly in a handful of SSA countries, including Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mauritius and Swaziland, all of which are LDCs except for Kenya and Mauritius. The value of these AGOA benefits is enhanced in that they are not conferred upon most other beneficiaries of GSP. However, AGOA apparel exports have been criticised from a development perspective for promoting mainly low wage, low skill manufacturing, as there is relatively little evidence that apparel manufacturing is promoting development of higher-skill manufacturing jobs.

The third category of AGOA exports, that is, other (non-oil, non-apparel) products, has been dominated by South Africa. South Africa has been the largest non-oil exporter under AGOA. AGOA benefits to exports of South Africa are extensive and diverse in a range of export sectors. Motor vehicles have been the largest export in this category, which also includes steel, chemicals, and agricultural goods (primarily citrus and wine).

The US Government has taken seriously enforcement of AGOA eligibility criteria with regard to democracy, governance and open markets. Over the first 15 years of AGOA’s operation, eligibility has been granted, suspended, and in some cases subsequently restored, to several potential beneficiary countries. Two countries that have benefited most from exporting apparel under AGOA have been affected: Madagascar was suspended in 2009 and restored in 2014, while Swaziland was suspended in 2015. As of the end of 2015, 39 SSA countries out of 47 potentially eligible countries qualified for AGOA benefits. As of the time of writing, South Africa was under threat of suspension of AGOA benefits for agricultural exports, pending resolution of US complaints that South Africa was improperly imposing antidumping duties on US chicken imports to South Africa. The US dispute with South Africa, the largest potential market for US exports to SSA, reinforces the argument made earlier that the USA has viewed the AGOA relationship as an opportunity to grow trade in both directions. Figure 1 shows that US exports to SSA countries have grown steadily over the duration of AGOA, notwithstanding major shifts in US imports from the same countries. While this growth in US exports may be attributable more to Africa’s economic growth over the period than to AGOA, since the latter confers no tariff benefits, US trade diplomacy with AGOA beneficiaries demonstrates the US interest in using AGOA to grow exports to SSA further.

AGOA-IV: opportunities and challenges

Since AGOA’s initial enactment in 2000 for a sevenyear period, AGOA has been extended three times. Most recently, the Trade Preference Extension Act of 2015 (AGOA IV) was signed into law in September 2015, extending AGOA benefits for ten years to 2025. Exporting firms in SSA have regarded the relatively short, fixed terms of AGOA tariff preferences and GSP preferences alike as disadvantageous in terms of making investment decisions to construct facilities intended to produce exports aimed at the US market. AGOA’s now longer term than GSP makes it easier for businesses to make sourcing decisions favouring African suppliers.

AGOA-IV contains some changes that create new opportunities and also new challenges for SSA governments and exporters. Among the opportunities, as noted above, AGOA-IV extends eligibility for apparel manufactured in ‘lesser developed’ AGOA beneficiaries using third country yarn and fabric for the full ten years. The renewal also broadens the RoO for non-apparel manufacturing to include the value of processing as well as material in the 35 per cent minimum AGOA (or US) content required for AGOA eligibility. This provision increases the potential for AGOA exporters to invest in non-apparel processing facilities for light industrial, consumer and agricultural goods. AGOA-IV mandates the development of biennial AGOA utilisation strategies through a ‘bottom up’ bilateral process between AGOA beneficiary countries and US trade capacity-building agencies (such as USAID). The strategies should promote small business and entrepreneurship, facilitate regional integration, and include plans for AGOA beneficiaries to implement the 2013 WTO Agreement on Trade Facilitation. AGOA-eligible countries can also draw on broader US initiatives, like ‘Trade Africa’, a policy initiative that seeks to increase regional trade within Africa and expand trade and economic ties between Africa, the USA and other global markets.

AGOA-IV’s primary new challenge is a stepped up US process for monitoring AGOA eligibility. Any interested member of the public (in addition to the President and United States Trade Representative) may now comment on annual AGOA eligibility reviews. In addition to annual eligibility reviews, any interested party may now petition USTR for an outof-cycle eligibility review, which can lead to change in a beneficiary’s AGOA eligibility at any time upon 60 days’ notice. The outcomes of such reviews must be shared with relevant Congressional committees. The process makes it easier for US industries competing with AGOA imports and US exporters facing market barriers in AGOA beneficiaries to challenge beneficiaries’ AGOA eligibility. AGOA-IV takes a more nuanced approach to promoting eligibility, however, empowering the President to suspend AGOA benefits or limit them to only certain imports rather than terminating AGOA eligibility entirely. AGOA eligibility has also been further constrained slightly by the addition of protection of women’s rights to the governance criteria.

Looking ahead: strategies for SSA export growth

After 15 years of AGOA, it is clear that substantial opportunities for exports from SSA countries to the USA have been created. Yet for SSA, AGOA’s benefits are narrower than they could be: a relatively small number of eligible countries and economic sectors actually benefit from AGOA preferences. The principal limitations of AGOA’s ability to open US markets to SSA exporters are threefold. First, AGOA, like GSP, is limited to tariff preferences. Average tariffs in the industrialised world have fallen to 3.8 per cent under successive GATT and WTO multilateral trade agreements. The very success of GATT and WTO tariff cuts has made non-tariff barriers a progressively more significant and effective means for industrial country governments to restrict imports. Second, the list of products eligible for duty-free imports under AGOA, while more extensive than the GSP list, is still limited, with many major agricultural products, including cotton, excluded and no provisions facilitating services exports. By contrast, the Morocco-USA FTA addresses some non-tariff barriers (e.g. intellectual property protection) and liberalises trade in services (under GATS supply modes 1, 2 and 3). Third, AGOA RoO for apparel are now significantly less favourable for non-LDC SSA exporters than the EU's single transformation RoO being implemented in connection with the EU-SSA EPAs. On that basis alone, some SSA exporters may find the US a comparatively less attractive apparel export market than the EU.

The USA has used AGOA effectively to pursue a mixture of trade and non-trade policy objectives with respect to SSA countries, all the while limiting to a set of tariff preferences the range of policy objectives available to SSA countries. In addition to AGOA and policy initiatives such as Trade Africa, Washington has pursued SSA trade policy objectives through signing Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) with a limited number of SSA countries, which facilitate investment flows, as well as Trade and Investment Framework Agreements (TIFAs) with a number of SSA states and regional groupings, which create mechanisms for dialogue on trade and investment issues. Although AGOA-IV directs the US Trade Representative to begin the process of negotiating reciprocal trade agreements with SSA countries similar to the EU-EPAs, the short-term prospects for any new trade agreements with the USA, given the domestic US political climate, are not auspicious. Nonetheless, and especially considering that TIFAs are in effect purely aspirational, the incentive remains strong for SSA countries to consider negotiating development-friendly reciprocal trade agreements with the USA, provided they support and strengthen SSA's own integration processes.

Given the current US political environment, AGOA beneficiaries can advance their trade interests best by taking advantage of AGOA-IV’s provisions and by lobbying for additional amendments to AGOA. AGOA-IV does not preclude further modification by legislative amendment. The probable continued high US dollar value is likely to fuel US protectionism among import-competing industries but should also make AGOA exports better value in US markets, generating support from importers and consumers. Moreover, SSA countries’ prospects for better trade relations with the USA should be strengthened by the increasing alignment of economic and security interests between the USA and SSA. Both share an interest in diversifying SSA trade and investment relations, as China’s interests in SSA have continued to deepen. Both also have an increasing interest in extending security co-operation in the face of ongoing threats of international terrorism.

An AGOA export strategy for SSA governments and exporters would be well advised to advance on two fronts: to take better advantage of existing and newly created opportunities under AGOA (including attracting export-oriented foreign direct investment to take advantage of these preferences); and to lobby for additional amendments that would open US markets further. Accelerating African regional economic integration (especially the envisaged Continental FTA) would facilitate prospects for developing supply chains within AGOA-eligible SSA for exports. Targeting and co-ordinating development investment and assistance on building out trade-related infrastructure (transport, storage, cold chain, customs administration, etc.) would facilitate more regional manufacturing and agricultural processing supply chains in addition to improving access and lowering costs for less accessible and landlocked SSA countries. Governments and the private sector need to coordinate closely in working with US counterpart agencies in developing and implementing the mandated bilateral AGOA utilisation strategies to take full advantage of available resources. Particularly important, AGOA beneficiaries need to pool and invest resources in effective political monitoring and representation in Washington to ensure that they have advance warning of any potential threats to AGOA eligibility and the ability to deploy effective political strategies to counter any such threats in future.

SSA countries should lobby for AGOA amendments, which could be attached to future ‘miscellaneous’ trade bills. These could seek to make AGOA at least as favourable as the Morocco-USA FTA with respect to non-tariff barriers and trade in services, to adopt more flexible RoO, and to expand AGOA’s product coverage in ways that would benefit most the eligible countries that have been least able to take advantage of AGOA. Cotton is a prime example. The ‘Cotton Four’ low cost cotton exporting countries (Mali, Burkina Faso, Benin and Chad) are now on the frontline in the global war on terror. The security argument for including cotton under AGOA, if not for reducing US cotton production subsidies, is compelling in the present environment.

Looking ahead, US exports to SSA are likely to continue growing, furthered in some cases by the leverage that AGOA eligibility provides and supported by initiatives like Trade Africa and the TIFAs. SSA exports to the USA are likely to increase gradually, but not driven by oil as in the past. Over the medium to long term, as oil prices once again rise, the USA is likely to provide for most if not all of its oil needs from North American production. In due course US oil demand can be expected to decline as more renewable energy sources come on stream, especially following the successful Paris Climate Conference, where all countries made commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and manage the impacts of climate change. (That said, given ongoing political instability in the Middle East, US demand for SSA oil exports, which originate from more stable and secure sources, could rise slightly again under particular circumstances.) Overall the diversification of AGOA exports by product and country of origin, which has already increased, is likely to continue to do so. Apparel exports should continue to grow, provided that existing RoO and AGOA eligibility for major apparel exporters are maintained. The major emerging challenge, however, is the conclusion of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which could give apparel-producing competitors, such as Vietnam, a competitive advantage over SSA exporters, like Lesotho, in the US market.

South Africa-USA trade relations will remain more complex. Considerable export potential for South African goods and services exists, but bilateral trade relations are more likely to resemble US trade relations with Asian tiger economies such as South Korea and Taiwan than US relations with other AGOA beneficiaries. Although South Africa is not as large an economy as its BRICS counterparts, namely Brazil, Russia, India and China, US exporters nonetheless view South Africa as a large potential market for US goods and want to see that market as open as possible, especially since South Africa offers tariff preferences to European competitors under an FTA and is now also part of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) EPA with the EU. However, it should be noted that past attempts to negotiate an FTA with the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) failed because of US demands for a comprehensive trade agreement that included ambitious and extensive new generation trade issues. Given the potential trade effects of the TPP (for SSA) and the EPAs (for the USA), there may arguably be a case for greater negotiating pragmatism and flexibility to consider development-friendly reciprocal preferential trade agreements.

Geoffrey Allen Pigman is Research Associate in the Department of Political Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Commonwealth Secretariat.

Commonwealth Trade Hot Topics is a peer-reviewed publication which provides concise and informative analyses on trade and related issues, prepared both by Commonwealth Secretariat and international experts.