News

The WTO, Nairobi and the 2030 Agenda

Against the backdrop of the latest WTO ministerial meeting can the multilateral trading system still deliver for the new UN sustainable development agenda?

Commentary on the outcome of the WTO’s 10th Ministerial Conference, known as MC10 in WTO parlance, held in Nairobi, Kenya in mid-December has been mixed. More optimistic accounts have hailed the adoption of a package of measures comprising six ministerial decisions on agriculture, cotton, and issues related to least-developed countries (LDCs) as significant and as an illustration of the continued capacity of the WTO’s negotiating function to deliver trade gains.

More pessimistic interpretations, however, see the Nairobi agreement as an abandonment of the 2001 Doha Development Agenda (DDA) in all but name and an open door for more exclusionary, plurilateral, and mega-regional trade deals.

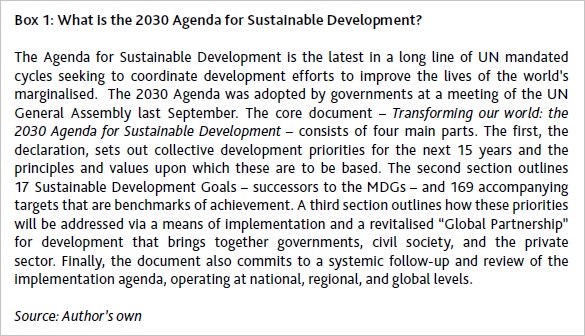

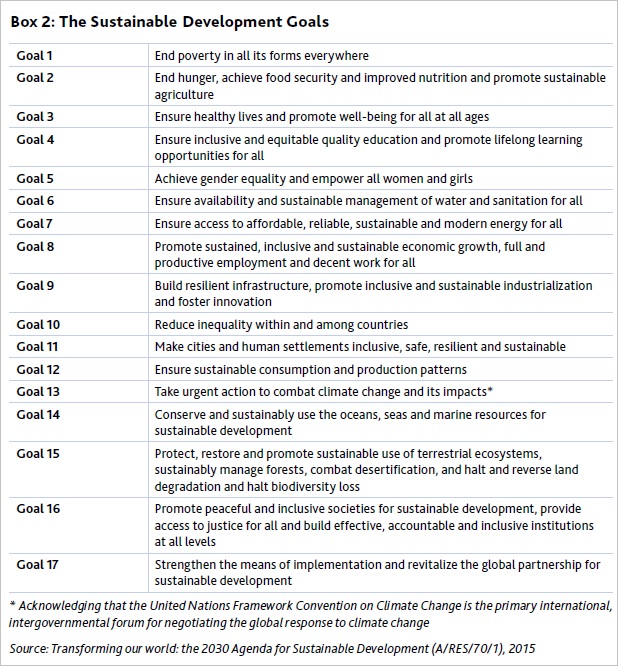

Yet while commentators have been quick to celebrate or bemoan the outcome of MC10, both in terms of the substantive gains it may bring or the impact it may have on the future of the multilateral trading system, almost no-one has asked what it means for the nascent 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The WTO’s negotiating function is now sufficiently problematic, and the organisation too peripherally placed, for the multilateral trading system to contribute as meaningfully to the realisation of the SDGs as had been envisaged.

This is a question worth asking. Given the significance of MC10 to revitalising the WTO’s negotiating function, and the place of that function in the realisation of the 2030 Agenda, it seems only prudent to reflect upon the impact that the Nairobi outcome is likely to have. This short essay explores the likely contribution of multilateral trading system to the 2030 Agenda in the wake of the Nairobi ministerial conference.

Trade in the 2030 Agenda

The previous Millennium Development Goal (MDG)-centred agenda made important moves towards embedding poverty reduction as a norm of international public policy making – if not practice – even if it was not wholly successful in galvanising the wherewithal to achieve the targets set.[1] One criticism of MDG regime was that it failed to bring the multilateral trading system into a global partnership for development, resigning trade-led growth and by extension growth-led development to an aspiration rather than a formal component of the global development order.

The 2030 Agenda seeks to correct this by bringing the multilateral trading system more centrally into the worldwide fight against destitution and immiseration. Yet, it is through a successful conclusion to the DDA – and crucially an outcome envisaged largely to be in accordance with the original Doha mandate – that the WTO and the multilateral trading system are to play a role.

Prior to the Nairobi ministerial the multilateral trading system had been set to play a more substantive role in the realisation of the 2030 Agenda than it had in the MDG-era. Trade had been cast as an engine for generating the kind of economic growth necessary to eradicate extreme poverty, for pressing forward with the elimination of destitution on a global scale, and for bringing welfare gains to all of the world’s populations.

Certainly, questions persisted as to whether the WTO was up to the challenge of driving forward the kind of trade-led growth envisaged in the 2030 agenda, and its capacity to play a full role was the subject of some scepticism as a result.[2] These questions had arisen not only because of the difficulties members have in concluding the Doha Round, but also because of the WTO’s peripheral role in shaping the 2030 Agenda and the less-than-spectacular record of the multilateral trading system in delivering gains for developing countries.[3] That said, the 2030 Agenda and the accompanying SDGs were nonetheless premised largely on an assumption that the Doha Round would eventually be concluded, that its conclusion would bear some resemblance to the original Doha mandate, and meaningful development gains would flow therefrom.

All change in Nairobi

Nairobi, however, changed all that irrecoverably. It threw into even sharper relief the mismatch between the function, direction, and orientation of the multilateral trading system and the means by which – and aspirations for – the realisation of the 2030 Agenda. In so doing, it relegated the WTO to a cameo role, and altered profoundly the relationship between the pursuit of multilateral trade openings and the realisation of substantive and meaningful development gains.

How and why is this the case? The agreement reached in Nairobi transforms the framework for conducting trade negotiations by moving it away from one targeted on delivering broad-based universal deals via a “single undertaking” to something more lithe and multi-faceted. This resulted because members proved unable to agree on whether or not to reaffirm the DDA in the Nairobi ministerial declaration thereby neither retaining nor abandoning it as the framework for future WTO negotiations.

Instead, rather than have the Nairobi negotiations flounder on a unbridgeable divide, members agreed to recognise their differences and to allow subsets of countries to pursue plurilateral negotiations in areas of interest to them. Only in cases where an attempt is made for new issues to be negotiated multilaterally – that is, across the membership as a whole – would universal consent be required.

It is because Nairobi resulted in a successful conclusion – and crucially opened the door for further negotiations to take place – that it is widely seen as rekindling faith in the organisation’s negotiating function and offering an important counter to the growth of “mega-regional” trade deals such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). Yet, it came at the expense of the DDA and the 14-year effort to agree to a wide-ranging multilateral deal on trade measures for development that has been a key demand of developing countries, and which has been crucial to securing their participation in the multilateral trading system.

The consequences of this decision, however, have significance beyond the Doha Round. The Nairobi outcome breaks with a near 40-year desire to conclude negotiations on a universal basis in the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) and the WTO.[4] Not only does the decision re-introduce a framework for negotiation permitting the conclusion of small group agreements that were a feature of many of the trade rounds prior to Uruguay (1986-1994), it also amounts to a recognition that the pursuit of universal agreements like the DDA is too difficult.

This, in turn, reduces the capacity of developing countries to secure trade-offs from developed countries in return for concessions in new areas as they had during the Uruguay Round when agreements in services, intellectual property rights, and investment measures, among other things, were given in return for agreements on agriculture, and textiles and clothing, as well as in an extension of special and differential treatment.

It is difficult to see how, in an era of mega-regional and plurilateral negotiations wherein the most commercially significant members negotiate market-opening deals among themselves, developing countries are likely to be able to gain significantly. And given that securing trade gains is a prerequisite of the 2030 trade-led growth and development strategy, it is hard to see how the Nairobi declaration will do anything other than hinder the capacity of the multilateral trading system to contribute meaningfully to the realisation of the SDGs.

It is worth bearing in mind that part of the rationale for launching the DDA on the basis of a single undertaking was to enable developing countries to secure the rectification of implementation anomalies and unfinished pieces of business from the Uruguay Round – particularly in agriculture – in exchange for any new trade concessions. Many of these remedial measures are seen by developing countries as important in helping realise the 2030 Agenda.

While it is the case that the Nairobi ministerial declaration commits members to the pursuit of development gains by other means, the only compunction to complete Doha is if there is a desire to open up negotiations in new areas on a multilateral basis. This is small beer indeed.

This outcome fundamentally alters the likely shape of future WTO deals. While the use of a critical mass negotiating mode brought participation and consensus into the core of the Nairobi talks, ironically it resulted in an agreement that enables members to move away from the pursuit of universal agreements wherein a balance of concessions is required that are acceptable to all members, to one in which more narrowly focused piecemeal negotiations can be pursued.

This less-than-universal approach to negotiating has a long history in multilateral trade and its return signals a move back to a more “mini-lateral” exclusionary mode of agreeing trade deals that has traditionally favoured developed countries over their developing counterparts.

The transformation of the WTO’s negotiating function into a much lither machinery is likely to preserve rather than attenuate this pattern. This does not necessarily mean that gains for the poorest and LDCs will be absent from future negotiations, but it does mean that they will almost certainly be of proportionately lesser value.

What now?

The future for the WTO and the multilateral trading system is mixed. On the one hand, it is clear that the Nairobi outcome will energise the multilateral system and enable the WTO to preside over future agreements. On the other hand, and in the absence of a universal endeavour, there is very little to force developed countries to focus on negotiations that are of specific interest to their developing counterparts.

The WTO’s negotiating function is now sufficiently problematic, and the organisation too peripherally placed, for the multilateral trading system to contribute as meaningfully to the realisation of the SDGs as had been envisaged. All we can hope for is that members make good on their commitment to pursue development gains by other means. The history of the Doha round and of the multilateral trading system more generally tells us that we should not hold our breath.

Rorden Wilkinson is Professor of Global Political Economy and Chair of the Department of International Relations at the University of Sussex, UK.

This article is published under BioRes, Volume 10 - Number 1, by the ICTSD.

[1] See Fukuda-Parr, Sakiko, and David Hulme. “International norm dynamics and the “end of poverty”: understanding the Millennium Development Goals.” Global governance: a review of multilateralism and international organizations 17.1 (2011): 17-36. Also Wilkinson, Rorden, and David Hulme. The Millennium Development Goals and beyond: global development after 2015. Vol. 65. Routledge, 2012.

[2] Wilkinson, Rorden. “Fit for Purpose? The Multilateral Trading System and the Post-2015 Development Agenda.” (2014).

[3] See Gowa, Joanne, and Soo Yeon Kim. “An exclusive country club: the effects of the GATT on trade, 1950-94.” World Politics 57.04 (2005): 453-478; Wilkinson, Rorden, and James Scott. “Developing country participation in the GATT: a reassessment.” World Trade Review 7.03 (2008): 473-510.

[4] The desire to conclude rounds on the basis of a single undertaking was a stated aim of multilateral trade negotiations as far back as the commencement of the Tokyo Round (1973-1979).