News

Breaking the gender earnings gap

Women in typically male sectors earn as much as their male peers and three times more than other women, according to a study in Uganda.

Betty Ajio has made a living for the past 23 years doing a job that most women would not think of doing.

The 43-year-old metal fabricator makes 120 to 230 cooking pots a day in Kisenyi, a slum in the heart of Kampala, Uganda.

Ajio and her four male employees operate in sweltering conditions. They shovel dirt and pour molten metal to make the pots. Ajio admits the work can be grueling, but says she would not trade her job for an easier one.

“I prefer doing this, because I think I can earn more than by selling clothes or vegetables,” she says.

Ajio is a fairly rare phenomenon in Africa and even globally as a woman in a male-dominated industry.

About 6% of female entrepreneurs in Kampala work, like Ajio, in a mostly male sector, says a study of 735 entrepreneurs in the city.

They earn, on average, as much as their male peers and three times more than women in more traditionally female sectors, according to “Breaking the Metal Ceiling: Female Entrepreneurs Who Succeed in a Male-Dominated World.”

Women around the world tend to be clustered in industries that see lower profits than sectors where men are dominant, according to the World Bank’s 2012 World Development Report on gender equality and development.

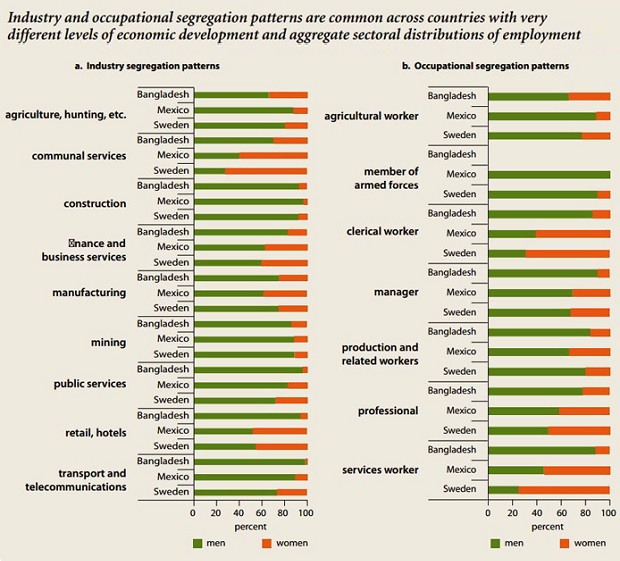

“The segregation of jobs by sex is something that you see in every country of the world,” from Sweden to Bangladesh, says economist Markus Goldstein, one of the 2012 WDR authors and the lead economist in the World Bank’s Africa Gender Innovation Lab. “It’s not something that automatically goes away with economic growth”

Gender segregation of the workforce is a “big component of the earnings gap between men and women,” he adds. “This is well known and the changes over time are well documented. The question is how to fix it.”

Goldstein was working on an entrepreneurship project in Kampala when he noticed a pattern in the findings that raised the question: What drives some women to venture into mostly male industries? Is there something different about them?

In what may be the first research of its kind, the “Breaking the Metal Ceiling” study tried to find out.

The study analyzed data collected in 2011 to see if the small number of women in male-dominated industries had special abilities or characteristics.

Goldstein says he fully expected the women to be “super-entrepreneurs. I thought it was easily about entrepreneurial ability. It turned out it wasn’t,” he says.

“In the sense of having abilities that are far above the average in any of the dimensions we could measure, that doesn’t appear to be the case.”

Instead, the biggest factors influencing women were support from their households and mentoring – in particular, from a male role model.

The women, dubbed “crossovers” by the researchers, were 3.5 times more likely to have been introduced to their work by a male family member. They were 80% more likely to have had a male role model than other women.

They were also much more likely to have been exposed to the sector at a relatively young age with the support of someone they trusted, typically a male, who helped them,” says Francisco Campos, a co-author of the “Breaking the Metal Ceiling” study.

The study was replicated in Ethiopia in 2014/15 to see if the results would be the same and to accumulate more evidence in the region. This study found that a woman’s husband seems to play an important role in helping her cross over to a male-dominated sector, says GIL economist Niklas Buehren. Husbands provide finance and also introduce women to the kinds of skills they need, and often the couple co-founds a business and go “together into that sector,” he says.

Often, however, crossovers are single – never married, widowed, or divorced.

And curiously, the crossovers were 93% less likely to have been influenced by their teacher, according to the Uganda study – perhaps because schools tend to reinforce traditional professions for women, says Goldstein.

“The real reinforcers of gender norms in Uganda are the teachers,” he says. “If teachers influenced you in your choice of profession, you’re going to be a hairdresser or a caterer.”

Another factor seems to be lack of information about how much people earn.

In Uganda, “more than 75% of women in traditional sectors that make less don’t know they make less, on average, than those who cross over. So there’s an information gap in general,” said Maria Muñoz Boudet, another co-author in the study.

Women in Ethiopia “didn’t seem to be aware that sector choice matters for income,” says Buehren. “It’s hard information to get, and there is a lack of data.”

Amid the bustle of Kisenyi’s metal fabrication production line, Ajio explains that her father introduced her to the trade. He was retiring from his business when he realized she could step into his shoes and make a good living. He encouraged her to take over and arranged for a friend to train her, she says.

Today she supports her seven children and two children of her siblings. She encourages other women to do the same kind of job – and several have come, she says.

A few steps away from Ajio’s workshop, Christine Lamum, 46, describes what she does as “jua kali” (a small-scale informal business) – manning one of many cauldrons in Kisenyi that turn car parts into liquid metal for the cooking pots. Lamum used to trade in vegetables in Gulu, a district in northern Uganda, but switched careers in 2002, after moving to Kampala to find a job. She saw men working in the slum and joined in, and now has enough money to send her eight children to boarding school, she says.

Lamum says she tells other women they could make their lives easier by doing what she does. “They shouldn’t minimize this kind of work because maybe it’s a man’s job. Everything is possible. Men and women can be equal.”

Given the studies’ findings, Campos says he thinks the next step should be a pilot project that provides information to women about opportunities in non-traditional fields, along with training and mentorship.

Developing countries should try to ease the path for women to enter male-dominated industries, says Goldstein.

“If you care about economies growing, then this seems like a much better way to get people to the jobs they’re better suited for – which would make your economy grow. It will also make those people happier, because you’re not ruling out whole professions for people. There’s more choice for them to find something that will make them happy, and it will also address gender inequality in earnings, so we’ll get more equality.”