News

New study: Illicit financial flows hit US$1.1 trillion in 2013

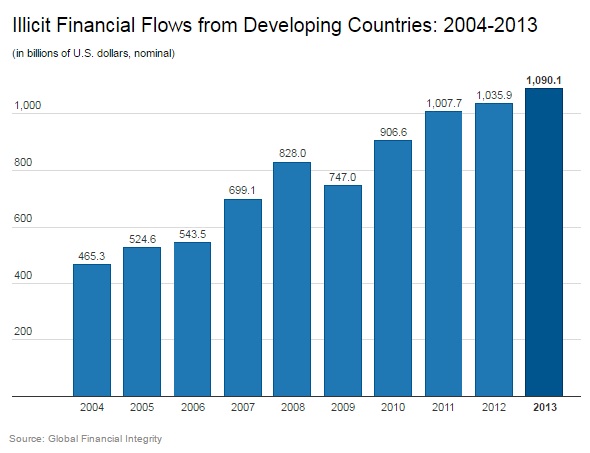

A December 2015 report from Global Financial Integrity finds that developing and emerging economies lost US$7.8 trillion in illicit financial flows from 2004 through 2013, with illicit outflows increasing at an average rate of 6.5 percent per year – nearly twice as fast as global GDP.

Illicit financial flows from developing and emerging economies surged to US$1.1 trillion in 2013, according to a study released on 8 December 2015 by Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a Washington, DC-based research and advisory organization. Authored by GFI Chief Economist Dev Kar and GFI Junior Economist Joseph Spanjers, the report pegs cumulative illicit outflows from developing economies at US$7.8 trillion between 2004 and 2013, the last year for which data are available.

Titled “Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries: 2004-2013”, the study reveals that illicit financial flows first surpassed US$1 trillion in 2011, and have grown to US$1.1 trillion in 2013 – marking a dramatic increase from 2004, when illicit outflows totaled just US$465.3 billion.

“This study clearly demonstrates that illicit financial flows are the most damaging economic problem faced by the world’s developing and emerging economies,” said GFI President Raymond Baker, a longtime authority on financial crime.

“This year at the U.N. the mantra of ‘trillions not billions’ was continuously used to indicate the amount of funds needed to reach the Sustainable Development Goals. Significantly curtailing illicit flows is central to that effort.”

This study is GFI’s 2015 annual global update on illicit financial flows from developing economies, and it is the sixth annual update of GFI’s groundbreaking 2008 report, “Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries 2002-2006.” This is the first report to include estimates of illicit financial flows from developing countries in 2013.

Primary Findings

US$1.1 trillion flowed illicitly out of developing and emerging economies in 2013, the latest year for which data is available. The illegal capital outflows stem from tax evasion, crime, corruption, and other illicit activity.

The report finds that from 2004 to 2013, developing countries lost US$7.8 trillion to illicit outflows. The outflows increased at an average inflation-adjusted rate of 6.5% per year over the decade – significantly outpacing GDP growth.

As a percentage of GDP, Sub-Saharan Africa suffered the biggest loss of illicit capital. Illicit outflows from the region averaged 6.1% of GDP annually. Globally, illicit financial outflows averaged 4.0% of GDP.

Trade Misinvoicing Dominant Channel

The fraudulent misinvoicing of trade transactions was revealed to be the largest component of illicit financial flows from developing countries, accounting for 83.4 percent of all illicit flows – highlighting that any effort to significantly curtail illicit financial flows must address trade misinvoicing.

Global Development Implications

The US$1.1 trillion that flowed illicitly out of developing countries in 2013 was greater than the combined total of foreign direct investment (FDI) and net official development assistance (ODA), which these economies received that year.

Illicit outflows were roughly 1.3 times the US$858 billion in total FDI, and they were 11.1 times the US$99.3 billion in ODA that these economies received in 2013.

Additional Findings

-

Illicit financial flows averaged a staggering 4.0 percent of the developing world’s GDP.

-

Sub-Saharan Africa suffered the largest illicit financial outflows – averaging 6.1 percent of GDP – followed by Developing Europe (5.9 percent), Asia (3.8 percent), the Western Hemisphere (3.6 percent), and the Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan, and Pakistan (MENA+AP, 2.3 percent).

-

In seven of the ten years studied global IFFs outpaced the total value of all foreign aid and foreign direct investment flowing into poor nations.

-

The IFF growth rate from 2004-2013 was 8.6 percent in Asia and 7 percent in Developing Europe as well as in the MENA and Asia-Pacific regions.

Major Implications for Domestic Resource Mobilization and Sustainable Development

Goal 16.4 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) calls on countries to significantly reduce illicit financial flows by 2030. However, the international community has not yet agreed on goal indicators, the technical measurements to provide baselines and track progress made on underlying targets and, subsequently, the overall SDGs. These indicators will not be finalized until March 2016. The report calls on the IMF to conduct this annual assessment.

Country Rankings

The study ranks the countries by the volume of illicit outflows. According to the report, the 20 biggest exporters of illicit flows over the decade are:

By Largest Average Illicit Financial Flows: 2004-2013

(in millions of U.S. dollars, nominal)

| Rank | Country | Average IFF |

| 1 | China | US$139.23bn |

| 2 | Russia | US$104.98bn |

| 3 | Mexico | US$52.84bn |

| 4 | India | US$51.03bn |

| 5 | Malaysia | US$41.85bn |

| 6 | Brazil | US$22.67bn |

| 7 | South Africa | US$20.92bn |

| 8 | Thailand | US$19.18bn |

| 9 | Indonesia | US$18.07bn |

| 10 | Nigeria | US$17.80bn |

| 11 | Kazakhstan | US$16.74bn |

| 12 | Turkey | US$15.45bn |

| 13 | Venezuela | US$12.39bn |

| 14 | Ukraine | US$11.68bn |

| 15 | Costa Rica | US$11.35bn |

| 16 | Iraq | US$10.50bn |

| 17 | Azerbaijan | US$9.50bn |

| 18 | Vietnam | US$9.29bn |

| 19 | Philippines | US$9.03bn |

| 20 | Poland | US$9.00bn |

Policy Recommendations

Illicit financial flows from developing countries are largely facilitated by continued opacity in the global financial system. This opacity reveals itself in many well-known ways: tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions, anonymous trusts and shell companies, bribery, and corruption. There are countless techniques to launder dirty money, including the misinvoicing of trade (TBML in this context), which is used to shift proceeds of criminal activity across national borders.

Though policy environments vary from country to country, there are best practices that all countries should adopt and promote at international and regional forums and institutions, including the G20, the G8, the United Nations, the World Bank, the IMF, the OECD, and the African Union. This section highlights those best practices and suggests further steps domestic and international regulators could take to curtail illicit financial flows.

Anti-Money Laundering

At a minimum, all countries should comply with the Financial Action Task Force Recommendations to combat money laundering and terrorist financing. The most recent update to those recommendations was released in 2012, introducing new priority areas on

corruption and tax crimes.

Despite good intentions and good policy, actually stopping money laundering often comes down to enforcement. Regulators and law enforcement officials must strongly enforce all anti-money laundering laws and regulations already on the books. This includes prosecuting criminal charges against and imposing appropriate penalties upon employees of financial intuitions who are culpable of allowing money laundering to occur.

Beneficial Ownership of Legal Entities

Countries and international institutions should require or support meaningful confirmation of beneficial ownership in all banking and securities accounts in order to address the problems posed by anonymous companies and other legal entities. Information on the ultimate, true, human owner(s) of all corporations and other legal entities should be disclosed upon formation, updated regularly, and made freely available to the public in central registries.

In 2015, the European Union adopted legislation requiring each EU Member State to create registers of beneficial ownership information by May 2017 that are freely accessible by law enforcement authorities and financial institutions, and available to third parties that can demonstrate a legitimate interest in the information. Nothing prevents EU Member states from creating entirely open registries, however, and a few countries both within and outside the EU have already committed to doing so, including the UK, Denmark, Norway and the Ukraine. However, progress by G20 countries towards meeting their High Level Principles on Beneficial Ownership Transparency (adopted by the G20 in November 2014) has been poor.

There are indications that other countries, especially those seeking the return of stolen assets, now recognize the negative impacts of anonymous companies as well. GFI urges countries to commit to the creation of public registries of corporate beneficial ownership information and to engage with countries already in the process of implementing public registers to learn from their challenges and successes.

Automatic Exchange of Financial Information

All countries should actively participate in the G20 and OECD-endorsed global movement toward the automatic exchange of financial information. Ninety-six countries have committed to implementing the OECD/G20 standard by the end of 2018, which represents some progress from this time last year, when 89 countries had committed. The OECD and G20 must ensure that developing countries, and especially the least developed countries, are able to participate in the process, even if that requires providing them with the necessary technical assistance.

Country-by-Country Reporting

All countries should require multinational corporations to publicly disclose their revenues, profits, losses, sales, taxes paid, subsidiaries, and staff levels on a country-by-country basis as a means of detecting and deterring abusive tax avoidance practices. As part of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative, the G20 countries and the OECD countries agreed in November 2015 to take the necessary measures to require their large, multinational companies to provide such reporting on a country-by-country basis. Unfortunately, the agreement only requires that the information be provided by the parent of the multinational company to its home tax authority. Other countries’ tax authorities will be able to access the information only through official treaty requests, and therefore only where such treaties are in place.

GFI strongly recommends that countries require their companies to provide public country-by-country reporting so that the information can be analyzed by legislators responsible for fixing the profit-shifting problems that such reporting will help identify. Since legislators alone will not have enough qualified people to adequately analyze the information necessary to make informed policy changes, publicly available country-by-country reporting will also allow experts from academia, civil society and the media to lend their analytical support to the problem.

Curtailing Trade Misinvoicing

Trade misinvoicing accounts for a substantial majority of illicit flows over the time period of this study, averaging 83.4 percent of IFFs or US$654.7 billion per year. Curbing trade misinvoicing must necessarily be a major focus for policymakers around the world.

Governments should significantly boost customs enforcement by providing appropriate training and equipment to better detect the intentional misinvoicing of trade transactions. One particularly important tool for stopping trade misinvoicing as it happens is access to realtime, commodity-level world market pricing information. This would allow customs officials to tell whether a good is significantly under- or over-priced in comparison to its prevailing world market norm price. This variance could then trigger an audit or another form of further review for the transaction.

Given the greater potential for abuse, trade transactions with secrecy jurisdictions should be treated with the highest level of scrutiny by customs, tax, and law enforcement officials. Brazil is an excellent example on this point, subjecting transactions with secrecy jurisdictions and tax havens to a higher tax rate.

UN Sustainable Development Goals/Addis Tax Initiative

While the SDG document is ambitious – it has 17 goals and 169 targets – the success of the illicit flows target may hinge on the indicator that is associated with it. The indicators, which will not be finalized until March 2016, are the underlying technical measurements that will show if progress is being made on the targets and, subsequently, toward the overall SDG goals.

A good indicator for 16.4 would be similar or identical to what GFI publishes each year in this annual update: a country-level estimate of illicit outflows related to misinvoiced trade and from other sources based on currently available data. Preferably, such an assessment would be conducted by the IMF in order to, in the first instance, create an IFF baseline for each country and then, over the longer-term, provide an indication of progress toward curtailing illicit flows. Without a baseline and annual assessments, it is unclear how it could be determined if the international community’s vision of significantly reduced illicit flows has been achieved. At the time of writing, the negotiations on this indicator have not reached a point where it can be determined if this level of tracking will be attempted or if it will be done so by a qualified international body.

The Addis Tax Initiative (ATI), another agreement reached in 2015, attempts to focus the political will of several countries to address the illicit flows menace. The ATI is the outcome of a side event at this year’s Financing for Development Conference agreed upon by over 30 countries and international organizations, and directly links illicit financial flows to domestic resource mobilization, and in turn, to sustainable development. Those governments and organizations have acknowledged that curbing illicit flows is crucial to achieving the SDGs.

Germany, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands are among the developed nations taking part in the non-binding effort to seek ways to reduce IFFs. Ethiopia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Tanzania, and other developing countries have said they will strive to curb their losses of revenue (due to IFFs). GFI strongly encourages other countries to sign on to the Addis Tax Initiative and has entered into discussions with many of these governments to determine how the aspiration of the Addis Action Agenda, the SDGs, and the ATI can move to implementation.

Methodology

To conduct the study, Dr. Kar and Mr. Spanjers analyzed discrepancies in balance of payments data and direction of trade statistics (DOTS), as reported to the IMF, in order to detect flows of capital that are illegally earned, transferred, and/or utilized. Since GFI’s 2014 annual update, the existing methodology has been refined to provide a more precise trade misinvoicing calculation for a greater number of countries, leading to a significant upward revision in illicit flow estimates for many of these economies as compared to previous GFI reports. Find out more ».