News

Africa trade and technology

Introduction

It is perceived that economic nationalism has slowed the meteoric rise of global trade. Since the Uruguay Round created the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, trade of goods and services has become a dominant feature in global economic growth. As a result, hundreds of millions of people in developing countries have graduated from subsistence living to middle-class status. The accession of China into the World Trade Organization in 2001 accelerated both the volume and character of global trade. By 2008, Global Value Chains (GVCs) have come to explain up to 70% of global trade volumes. GVCs optimize comparative advantage across borders and have enabled innovation in trade logistics and services technologies, in addition to a general WTO commitment by member states to facilitate trade.

However, the renegotiation of liberal free trade agreements, such as Brexit and the reconsideration of NAFTA, and the concomitant shift of manufacturing jobs (on-shoring) back into developed economies have accelerated. In the latest WTO Report on G20 Trade Practices, $481 billion in new import restrictive measures were imposed by G20 members in 2018. This is the largest increase of such measures ever recorded by the WTO and six times larger than last year’s. Also, according to the World Bank, the growth in GVC’s has stalled. The WTO appears unable to broker more ambitious global agreements among member states, and there is a perceptible decline in confidence in the organization’s ability to evolve the rules-based global trading system.

The question of Africa’s ability to adapt to these shifting trends in trade must be analyzed in light of its participation in the global economy and its ability to adopt the tools to become more competitive in a world of rapidly evolving technology and supply chains. It should be noted that this analysis will concentrate on sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and will disaggregate data accordingly, whenever possible. Africa has enormous diversity amongst its 54 nations and even among its regions. This chapter will examine the political economy of Africa’s trade and identify constraints and opportunities that will define its future, including the adoption of artificial intelligence.

Africa and Global Trade

Pliny the Elder is known for two contributions to global learning. One is the discovery of hops as an essential ingredient for brewing beer and the other for the phrase: “ex Africa semper aliquid novi” (always something new out of Africa). What is new about Africa has been the African rising story. While this optimistic narrative is a departure from the doom and gloom scenario of the past, there are storms on the horizon.

The 1970s saw the promise of independence fade into dysfunction, predation, and manipulation by super powers fighting proxy wars across Africa. South Africa, the continent’s most advanced economy, was roiled by Apartheid and the opposition to it, which spread beyond its borders and stifled trade. Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, was riven by a succession of weak civil governments succeeded by oppressive military regimes, all marked by odious levels of corruption. Development assistance from multilateral and bilateral sources contributed to economic distortion and suffocating levels of indebtedness. As a result, Africa’s portion of global trade had fallen from 3.5% in 1971 to 1.5% in 1999 and consisted mostly of unprocessed goods.

Adding insult to injury, Africa was largely left out of the global trade negotiations under GATT and WTO and thus unable to shape its own economic future. When coupled with the devastation of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, by the 1990s, Africa was on the economic ropes. Famously, in May 2000, The Economist published a feature on Africa entitled “The Hopeless Continent.” African trade statistics notoriously fail to quantify the size of the informal economy and the volume of informal trade of goods and services both internal and externally. A recent IMF study revealed that in Benin, Nigeria, and Tanzania about 65% of the economy is informal.

Current Trade Situation

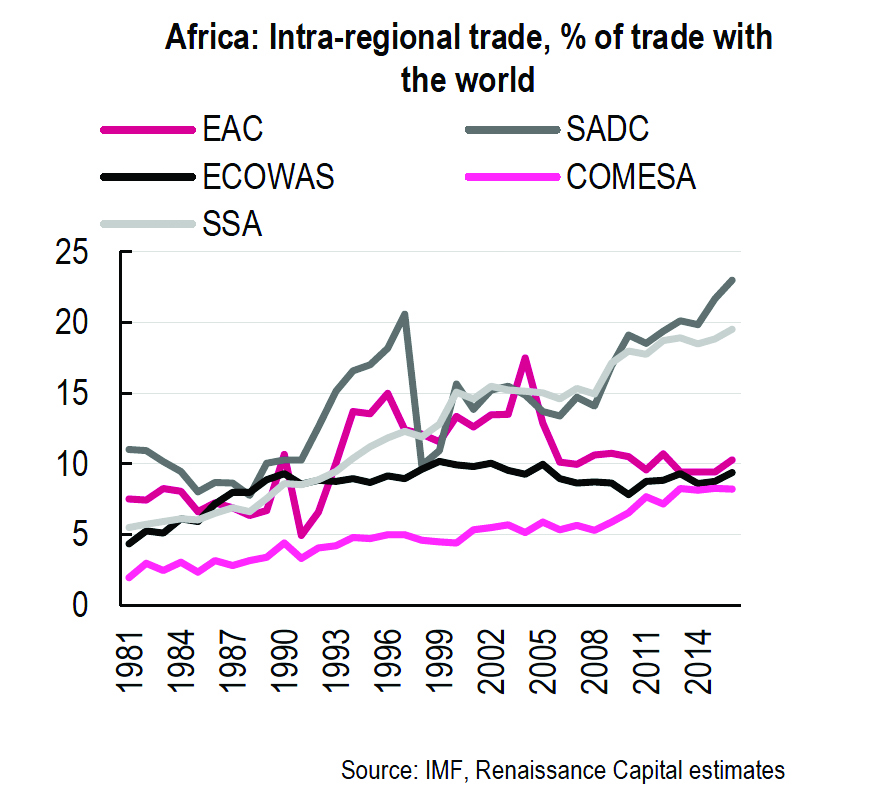

Nearly twenty years since The Economist declared it doomed, sub-Saharan Africa remains the most under connected region in the world. While absolute trade has increased, the region represents about 2-3% of global trade volume and intra-Africa trade accounts for about 11% of total exports as seen by the below chart comparing Africa’s leading Regional Economic Communities (RECs). These include the East Africa Community (EAC), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) and the Common Market for East and Southern Africa (COMESA). SSA represents Sub-Saharan Africa. This contrasts sharply with South America (22%) and Western Europe (70%).

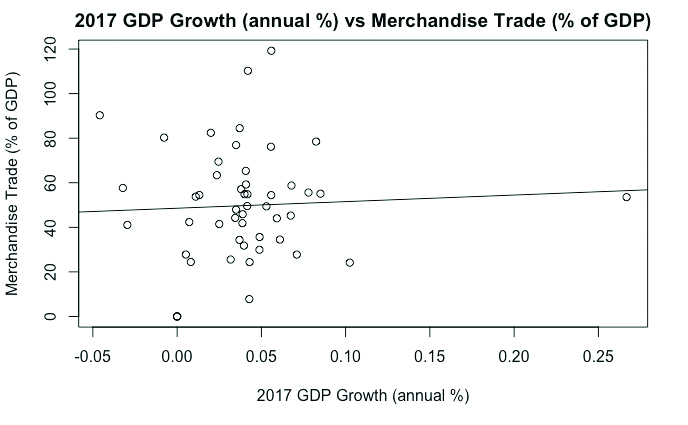

Sadly, what little trade that has occurred remains in raw commodities, mostly agricultural and mineral products. Although economic orthodoxy has long concluded that open markets beget economic growth, our evaluation of World Bank data has shown that there is a very weak correlation between economic growth and merchandise trade.

The most compelling explanation of this is that most external trade from Africa is tied to raw commodities and offer few forward and backward linkages to the local economy. This is in contrast to intra-Africa trade which favors manufactured, fast moving, and consumer goods. There are many reasons for the lack of intra-African trade including:

-

Weakness of physical and human infrastructure (more on this later)

-

Small size of individual African country markets

-

Residual tariffs and onerous non-tariff measures (NTM) on processed and semi-processed African products by both developed and emerging markets

-

Export constraints and other pre-border barriers

-

Absence of trade finance

-

Institutional constraints on enterprise growth and inability to achieve scale

-

Currency risk

-

Corruption and rent-seeking clientelism

-

Civil disruption

Infrastructure

[P]rior to independence, physical infrastructure was designed to satisfy the security concerns of competing European powers and related commercial interests seeking access to Africa’s natural resource bounty. While multilateral and bilateral development assistance fueled a surge of investment in infrastructure in the early years of statehood, many of these investments suffered from poor design and lack of maintenance. In other regions, private investment in infrastructure provided higher yields. For Africa to enhance its trade competitiveness internally and externally, trade related to physical and human infrastructure must be enhanced. This is no mean task. In its most recent analysis, the Africa Development Bank has estimated that Africa needs approximately $170 billion per year in infrastructure investment development, of which 20% is available from African sources.

Market Access

Another obstacle is the resistance of foreign markets to open themselves to African value-added exports. These constraints can occur in the form of tariff biases. For example, cocoa is offered duty free access into the U.S. market, but chocolate is subject to duty. While meat products could enjoy access to European markets, Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures thwart these opportunities, often at the behest of protectionist interests. And despite all the rhetoric toward South-South cooperation, China provides duty free access to fewer African products than the United Sates, and it only does so for those countries that fall under the UN’s least developed country definitions, thereby excluding the most export ready economies. Non-tariff measures equally restrict South-South trade and South-North trade.

In order to partly remedy these deficiencies and respond to world opinion, G-8 countries have enacted several trade initiatives in the past twenty years, including the U.S. Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and the European Union’s Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA). AGOA was passed in 2000 and expanded upon the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) by allowing over 6,000 items from qualifying sub-Saharan African nations into the U.S. market on a zero-duty and nonreciprocal basis. AGOA was supported by over $1 billion of trade-related development assistance, largely through USAID’s Africa Trade Hubs. This market access requires minimal compliance with various standards such as labor and human rights and general business norms.

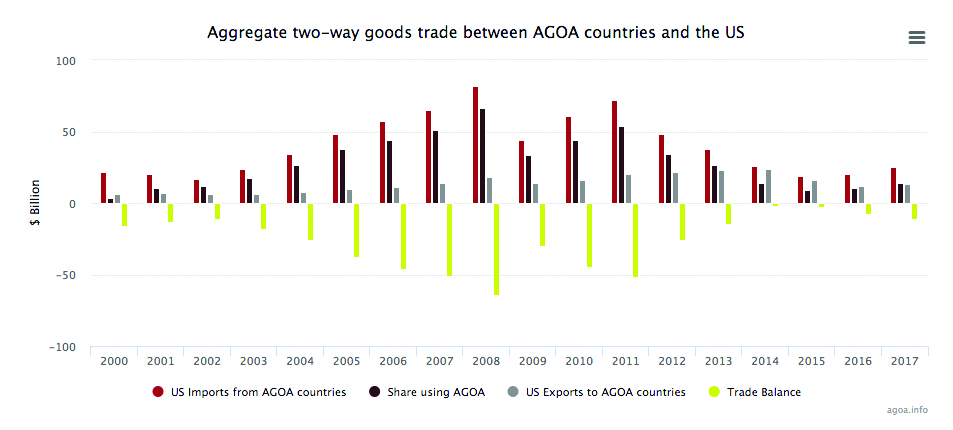

In 2015, AGOA was extended until 2025, when it is assumed that a more reciprocal agreement is likely. In the past few months, the Trump administration has indicated its intent to negotiate bilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with willing African nations. As seen in Figure 3, AGOA has achieved modest direct and indirect results. While total two-way trade between Africa and the United States has trebled between 2000 and 2017, the vast majority of the trade has been in petroleum or mineral related products with the most amount of manufactured and agricultural goods limited to a few countries.

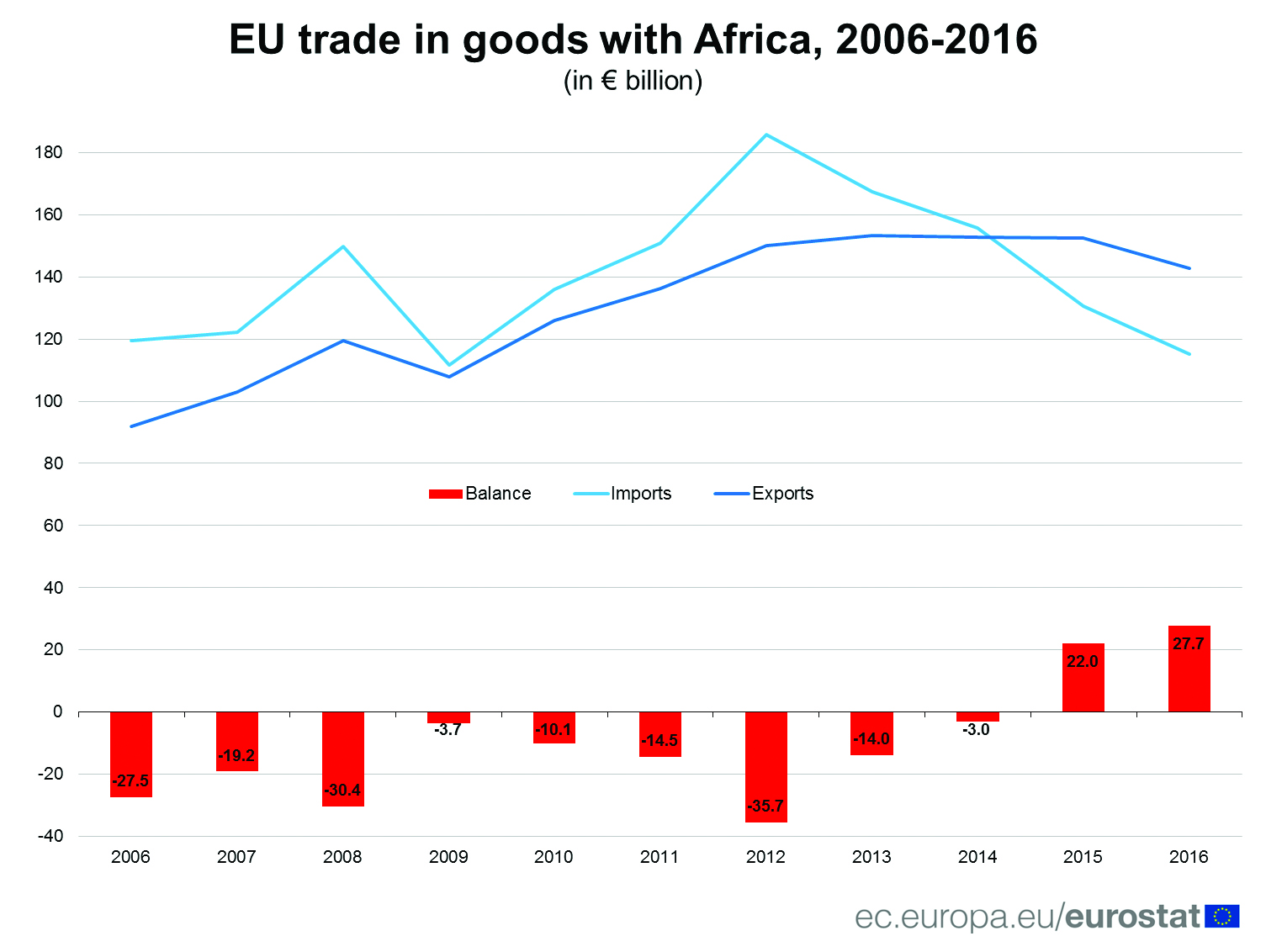

The EU’s EPAs are neither as generous nor comprehensive as AGOA. These agreements are an extension of the Lomé agreement of the 1980s and are available to all qualifying African, Pacific, and Caribbean (APC) countries. While they have much more generous provisions than the Lomé agreement, they also require qualifying countries (which include all but the poorest APC countries) to open their markets to European exporters. As seen [below], the results have been inconclusive.

Regional Trade

One of the barriers to intra-Africa trade has been the evolution of a system of regional trade agreements with often conflicting and always confusing results. In order to define its own economic future and accelerate intra-Africa Trade, in 2018, the leaders of 44 African countries signed an agreement to establish the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA). This agreement aims to establish the world’s largest geographic free trade arrangement by 2019. When in force, the AfCFTA will remove trade obstacles such as tariffs, quotas, and NTMs to accelerate the flow of goods and services amongst member states. Such integration is also aimed at increasing Africa’s partnership in GVCs. So far, only 14 countries have ratified the agreement and Nigeria has voiced opposition to the agreement. While the achievement evidences a monumental shift in ambition, it remains to be seen whether this will be transformative as Africa’s supply capacity has always limited the impact of market access agreements.

Services

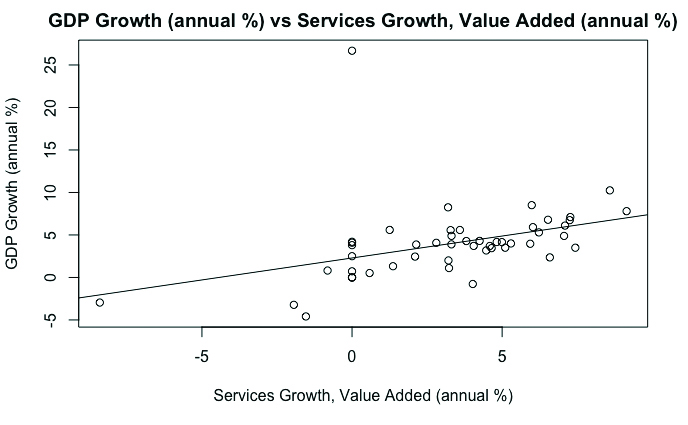

One area where supply constraints have been less daunting is the services sector. Services are less limited by physical barriers and have been greatly impacted by the growth of telecommunication and internet access across Africa. The impact has been dramatic, and there is evidence of a positive correlation to GDP growth.

According to a Brookings report, services exports grew six times faster than merchandise exports between 1998 and 2015. According to the World Bank’s most recent data, 53.2% of sub-Saharan African GDP is attributed to services. And in Ethiopia and Ivory Coast, the services sector grew respectively by 8.59% and 9.15% in 2016. Kenya, Rwanda, and South Africa have undertaken special measures to grow their services sectors and become knowledge based economies. Botswana has become the global center for diamond sales. However, services expansion is dependent upon access to media and the Internet, and some African countries have put constraints on access in order to suppress political dissent.

Human Capacity

A key component crucial to fostering a prosperous economy is a country’s ability to develop its human capital, or the benefits people can provide, given their knowledge, skills, and work ethic, to an economy. Unfortunately, many African countries are far behind their developed counterparts in this area, greatly hurting their economy in the present and likely in the future. This can be attributed to the collapse of post-secondary education institutions, lack of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) related programs, and the limited possibilities for those who are educated. Although there is some hope on the horizon for these struggling countries, they still have a long way to go.

Due to the economic downfalls for the majority of the continent, Africa is seeing a huge brain drain among those with higher education; qualified professionals are leaving their home country to pursue better opportunities in other countries, typically in the United States or Europe. Those who do receive a good education in Africa are often incentivized to leave for higher paying jobs, a better quality of life, or more opportunities in other countries, thus leaving their home country worse off. The loss of potential workers leaves Africa increasingly reliant on bringing in workers from outside countries, which then hinders building up local skills in the community.

Despite all that Africa has stacked against it, there is hope for its developing countries. Africa has the fastest growing middle class in the world, with the potential to grow its labor force immensely. It has a huge population of untapped potential that could be fixed with innovations and proper allocation of funding. Two changes Africa needs to make are improving school systems and pursuing technological advancements. Innovation is crucial for an economy to prosper, and the way to do that is through improved technology. Access to communications technology has the ability to dramatically improve the efficiency across all countries and give people the means to connect to one another. Similarly, growing the education systems will allow students to get a better education and grow up to contribute to the community. Young adults will be better prepared to enter the workforce and have the tools they need to push the economy into a place that can be beneficial for all. These adjustments will not be easy, but if governments and citizens can come together and develop better policies at all levels, change can happen.

Investment: Africa Rising

A brief mention should be made of Africa’s changing investment landscape. The Africa Rising scenario has become a popular mantra over the past decade and a departure from the Natural Resource Curse scenario that dominated African inward investment for decades. With a growing middle class, a growth in demand in Asia for commodities, and a suite of economic reforms, Africa has once again become a more attractive investment destination. While currency and limits on repatriation of earnings still exist, private equity funds are searching for the higher yields that Africa can offer. Private investment and money remittances from the African diaspora now both exceed the amount of inward development assistance flows. China has made a contribution, first by its state-owned companies and now by 10,000 private companies operating in the continent. However, much of the Chinese capital is in the form of medium- and long-term debt or is bartered in exchange for access to desired natural resources. Surprisingly, according to EY, the United States is still the leading investor into Africa outside of the African continent as measured by the quantity of investments. Within Africa, South Africa and Kenya has become leading investors as they bring not only capital but also access to world-class capital markets.

Although low investment returns in the developed world have incentivized investors to look for opportunities in emerging markets, Africa has set up many obstacles to FDI. First, with the exception of Kenya and South Africa, Africa’s capital markets are weak and offer few opportunities for investors to find attractive exits or raise complimentary capital. Second, Africans need more ambition with regards to the reform agenda, especially as there is compelling evidence that coherent, predictable, and transparent enabling environments are a precondition for investment. The World Bank’s annual doing business survey provides ample evidence of an ongoing African reform agenda. While four of the world’s top ten reforming economies are located in Africa, six of the bottom ten countries in the ease of doing business rank are located in Africa. While some African countries benchmark against other African countries, the reality is that, in a world of GVCs, each country in Africa competes with not only fellow Africa countries but also emerging markets everywhere.

Automation & Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Africa

Enabled by artificial intelligence (AI), machines can learn from patterns in data and proactively improve themselves, bringing human-like cognition to industrial automation and disrupting modes of production and the delivery of services. Global investment in AI has rapidly increased to between $20 billion USD and $30 billion USD in 2016, with 90% allocated to research, development, and deployment, and 10% to acquisitions. Much of this capital comes from companies like Google, Amazon, and Baidu. But there is also a growing contingent of private equity and venture capital investors, which spent between $5 and $8 billion in 2016.

The abundance of interest, capital, opportunities, and promises reminds one of mobile technology just 10 years ago. Will automation and AI do to African nations over the next decade what mobile technology did to them in the last one, fueling a dramatic rise in connectivity and unlocking significant gains in economic development? Like mobile technology and communication capabilities, will automation and AI permit African nations to dramatically increase their research, development, and production capabilities? Will automation and AI give African nations even more power to leapfrog the need for old-fashioned infrastructure and outdated strategies of industrialization?

African leaders, entrepreneurs, investors, and policymakers have the opportunity to leverage automation and AI to improve agriculture and manufacturing in particular. With greater productivity, efficiency, and safety, these high-growth sectors enabled by innovative technology and human capacity can advance sustainable development, maintain inclusive growth, and connect supply chains regionally and globally. PricewaterhouseCoopers estimated that AI technologies could increase global GDP by $15.7 trillion, a full 14%, by 2030, of which $1.2 trillion would be added for Africa. But these outcomes are not possible without considerable challenge and significant investment.

Critical components necessary for automation and AI to take hold are missing across most of the continent except in a handful of countries – namely Kenya, South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Ethiopia, and Botswana. For one, the lack of quality first-generation internet and communications infrastructure leaves little to replace and a heavy burden for mobile networks to process the computationally dense work of AI at scale.

Internet connectivity still costs too much for most people; and many of those that can afford it still complain of poor service. Plus, further improvements to human capacity are also required to speed uptake and adoption of the new features afforded to users by automation and AI. Finally, many African countries remain incapable of requisite reforms in the areas of data collection and data privacy, infrastructure, education, and governance.

But there are also opportunities at large and tools available to solve problems and accelerate progress. Mobile technology should be seen as the foundation for automation and AI. A youth culture of strong interest in business creation is a driving force of technology adoption and development, with many young entrepreneurs looking for global opportunities. Internet connectivity has nonetheless provided unprecedented access to information, partnership, and capital.

Automation & Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture

The Global Opportunity Network’s 2016 Report identified smart agriculture as the opportunity with the biggest potential for a positive impact on society – ahead of the digital labor market and closing the skills gap. After all, with 2.3 billion more people in the world by 2050, we will need to produce 70 percent more food than we do today amidst climate change, resource scarcity, and growing inequality. Nowhere are these pressures felt more sensitively than in Africa. Agriculture employs 60 percent of Africa’s workers and produces nearly a third of its GDP.

Until 2025, agriculture will create more jobs than the rest of the economy combined. Buoyed by the increasing demands of population growth and the increasing supply pressures of climate change, agriculture will continue to be a critical pillar of Africa’s economic growth and meaningful participation in the changing global trade landscape. As such, improving productivity and efficiency of agriculture and food processing is an important objective for countries in Africa, who can accomplish this goal with the help of automation and AI.

But the challenges are plenty. For one, there is more uncultivated arable land in sub-Saharan Africa than there is cultivated farmland in the United States, and that land needs to be utilized more effectively and efficiently. Barriers to accessing financing for modernization persist, so it remains difficult and expensive to do so. Young working-age people are leaving rural homes for cities, attracted away from farming to what are perceived to be more ‘innovative’ industries. Climate change, disease, and drought also remain formidable and will almost certainly become more severe in the future. Nevertheless, automation and AI can help solve these, too.

Automation & Artificial Intelligence in Manufacturing

Manufacturing represents almost a third of African countries’ GDP. Overseas Development Institute data show that between 2005 and 2014 manufacturing production within Africa more than doubled from $73 billion to $157 billion, growing 3.5% annually in real terms. Uganda, Tanzania, and Zambia have achieved more than 5% annual growth in the recent past. Manufacturing exports from sub-Saharan African markets almost tripled between 2005 and 2015 to more than $140 billion. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in African manufacturing is increasing and increasingly comes from other parts of Africa. Manufacturing investments represent a quarter of all FDI in Mozambique and Tanzania and more than 40 percent in Rwanda. Indeed, The Economist calls Africa “an awakening giant” in 2014; and Irene Yuan Sun, author and consultant, writing in Harvard Business Review in 2017 considered Africa “the world’s next great manufacturing center.

Improvements to manufacturing through automation and artificial intelligence (AI) can accelerate diversification of African economies, increase resilience to economic and climate shocks, and decrease dependence on natural resource exports. Automation and AI have the potential to expand manufacturing capabilities for aerospace, military, medical, dental, textiles, and automotive, all high-growth, high-value sub-sectors. Egypt, Tanzania, Morocco, South Africa, Tunisia, and Kenya are stand-out leaders in terms of pro-manufacturing policy, incentives for investment, and environments for experimentation and commercialization of automation and AI in manufacturing.

Big Data

Automation and artificial intelligence (AI) require large amounts of data from which to find patterns and make predictions. While mobile phones and the growing popularity of social media and messaging applications across Africa have made data more readily available, there remain shortages and barriers. Even in countries where automation and AI hold promise, the quality, timeliness, and availability of data are often poor in quality or missing.

In sub-Saharan Africa, Kenya leads in internet penetration, mobile density, and in trade in ICT services. Expanding internet access on the continent has led to a 25% increase in GDP, worth $2.2 trillion, and 140 million jobs. Even more fundamental than internet access, automation and AI no matter how innovative and disruptive still require basic ICT infrastructure, education, and improved cost and reliability of electricity.

Developing, Not Automating, Human Capacity and Skill

More than just big data, automation and artificial intelligence (AI) rely on significant know-how among its human adopters. No one knows for certain if productivity gains from automation will create more jobs than it destroys, as has occurred during previous technological shifts. The labor effects of automation and AI are often painted as a zero sum, but the truth is more nuanced. The Future of Jobs Report in 2018 predicts the loss of 75 million jobs by 2022 and the creation of 133 million jobs over the same period, for a net increase of 58 million jobs. In other words, innovative technology like automation and AI may create more jobs than it destroys.

Rather than displacing employees, machines can empower low-skilled workers and equip them to take on more-complex responsibilities. This, in turn, can help meet an urgent need for countries lacking widespread access to education and skills training.

Similarly, a World Economic Forum report suggests new technologies have the capacity to both disrupt and create new ways of working, similar to previous periods of economic history such as the Industrial Revolution, when the advent of steam power and then electricity helped spur the creation of new jobs and the development of the middle class. But workers and the systems that educate and train them need to be ready. Significant investment should be maintained in developing human capacity from primary school to university. For instance, backed by Google and Facebook, the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences (AIMS) has created the first dedicated master’s degree program for machine intelligence in Africa.

Way Forward to Enabling Automation, Artificial Intelligence, and Their Benefits

Will automation and AI fuel economic development and research as mobile technologies did in the past decade? Will they allow African nations to leap ahead, skipping traditional industrialization steps? The answers to these questions remain elusive, and in many respects it remains too early to tell. But for any chance at positive outcomes – that is, for African countries to fully leverage the power of automation and AI to change sectors like agriculture and manufacturing into globally-connected productivity powerhouses – governments and private sector alike must fully understand the advantages and consequences of this technology and deliberately respond to integrating it into national strategy.

Government leaders should focus on three (3) key activities:

-

Increase financing of internet and communications technology infrastructure development

-

Integrate technology education into curricula of primary and secondary schools;

-

Implement reforms to data collection and data privacy policies.

There is an urgent need to accelerate improvements to the agriculture and manufacturing sectors to increase their value alongside other efforts to diversify African economies, strengthen growth, and build resilience. Given the leapfrogging lessons of mobile technology on the continent over the last two decades, many African countries are positioned well to leverage automation and AI with agility and innovation. Automation and AI in agriculture and manufacturing would unlock tremendous value, connecting these markets to new regional and global marketplaces and allowing them to compete more efficiently and effectively. The challenge lies not in maneuvering these technologies as a vehicle but in ensuring that government, industry, and civil society contribute to creating an enabling environment.

The above extracts are taken from an article published via Governance In An Emerging New World – Winter Series, Issue 119, on the theme Africa in an Emerging World. The authors are Anthony Carroll, a vice president at Manchester Trade Ltd., and Eric Obscherning, an associate consultant at C&M International.