News

New focus needed to raise global competitiveness: WEF report

Ten years on from the global financial crisis, the prospects for a sustained economic recovery remain at risk due to a widespread failure on the part of leaders and policy-makers to put in place reforms necessary to underpin competitiveness and bring about much-needed increases in productivity, according to data from the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018, published today.

The report is an annual assessment of the factors driving countries’ productivity and prosperity. The report’s competitiveness ranking is based on the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), which was introduced by the World Economic Forum in 2005.

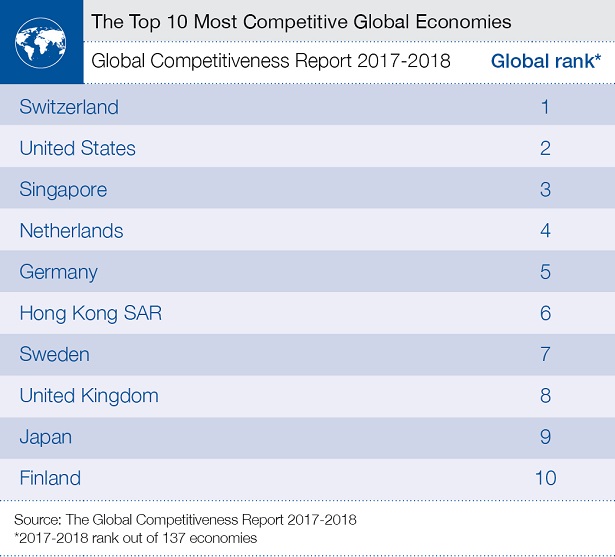

For the ninth consecutive year, the report’s GCI finds Switzerland to be the world’s most competitive economy, narrowly ahead of the United States and Singapore. Other G20 economies in the top 10 are Germany (5), the United Kingdom (8) and Japan (9). China is the highest ranking among the BRICS group of large emerging markets, moving up one rank to 27.

Drawing on data going back 10 years, the report highlights in particular three areas of greatest concern. These include the financial system, where levels of “soundness” have yet to recover from the shock of 2007 and in some parts of the world are declining further. This is especially of concern given the important role the financial system will need to play in facilitating investment in innovation related to the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Another key finding is that competitiveness is enhanced, not weakened, by combining degrees of flexibility within the labour force with adequate protection of workers’ rights. With vast numbers of jobs set to be disrupted as a result of automation and robotization, creating conditions that can withstand economic shock and support workers through transition periods will be vital.

GCI data also suggests that the reason innovation often fails to ignite productivity is due to an imbalance between investments in technology and efforts to promote its adoption throughout the wider economy.

“Global competitiveness will be more and more defined by the innovative capacity of a country. Talents will become increasingly more important than capital and therefore the world is moving from the age of capitalism into the age of talentism. Countries preparing for the Fourth Industrial Revolution and simultaneously strengthening their political, economic and social systems will be the winners in the competitive race of the future,” said Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman, World Economic Forum.

For more on all the key findings of the Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018, click click here.

The Global Competitiveness Index in 2017

With Switzerland, Netherlands and Germany remaining stable on first, fourth and fifth spots respectively, the only changes in the top five apply to the United States and Singapore, which swap second and third positions. Elsewhere in the top 10 the big winner is Hong Kong SAR, which jumps three places to sixth, edging out Sweden (7), UK (8) and Japan (9), all of which decline one place. With Finland holding stable in 10th position, the other big winner in the top 20 is Israel, which climbs eight places to 16.

In Europe, the region’s third-largest economy, France, is edged out one position to 22. Elsewhere, there seems little sign of improvement in addressing the region’s north-south divide with little change in the rankings of Spain (34), Italy (43), or Greece (87). Portugal does excel though, climbing four places ahead of Italy to 42. General trends over the past decade have seen an improvement in aspects of Europe’s innovation ecosystems but a worrying deterioration in some important education indicators. Russia improves five positions, moving to 38. Improvements in basic requirements and innovation drive the increase.

North America remains one of the most competitive regions in the world. Leading in innovation, business sophistication and technological readiness, and ranking close to the top in the other pillars of competitiveness. The United States rises to number 2 and Canada also improves one position to 14.

Among the 17 East Asia and Pacific economies covered, 13 have increased their overall score – albeit marginally – with Indonesia and Brunei Darussalam making the largest strides since last year. Singapore, the most competitive economy in the region, slipped from second to third place, while Hong Kong advanced from ninth to sixth place – passing Japan, now ranked ninth. There have been signs of a productivity slowdown among the region’s advanced economies and in China, suggesting the need to pursue efforts to further increase technological readiness and promote innovation.

India (40th) remains the most competitive country in South Asia, as most countries in the region improve their performance. The two Himalayan countries of Bhutan (82nd, up 15) and Nepal (88th, up ten) are among the most improved countries globally while Pakistan (115th, up seven) and Bangladesh (99th, up seven) have both improved their scores across all pillars of competitiveness. Improving ICT infrastructure and use remain among the biggest challenges for the region: in the past decade, technological readiness stagnated the most in South Asia.

Latin America and the Caribbean have seen 10 years of continued improvement in competitiveness. Chile continues to lead the region at placing 33, followed by Costa Rica ranked 47 and improving seven positions. Panama comes next, ranking 50 and falling eight positions. Argentina showed most improvement, placing 92 and going up 12 positions. Brazil stabilizes at 80, improving one position, as well as Mexico ranked 51st. Colombia and Peru each fall five positions, ranking 66 and 72 respectively. Last in the region comes Haiti and Venezuela.

The Middle East and North Africa improves its average performance this year, despite further deterioration in the macroeconomic environment in some countries. Low oil and gas prices are forcing the region to implement reforms to boost diversification, and heavy investments in digital and technological infrastructure have allowed major improvements in technological readiness. However, these have not yet led to an equally large turnaround in the region’s level of innovation. The United Arab Emirates (17th) leads the way among the Arab countries followed by Qatar (25th), while the most-improved country is Egypt (101st, up 14)

On average, sub-Saharan Africa’s competitiveness has not changed significantly over the past decade and only a handful of countries (Ethiopia 108, Senegal 106, Tanzania 113, Uganda 114) are continuing to improve this year. Leading the ranking in the region come Mauritius (45), Rwanda (58), South Africa (61) and Botswana (63). In general, Africa is still being penalized by its macroeconomic environment. Average inflation grew to double digits last year while public finances are still being affected by relatively low commodity prices, which curbed public revenues and hence government investments. At the same time, Africa’s financial markets and infrastructures remain underdeveloped, and institutions’ improvement process hit a setback this year as political uncertainty is growing in key countries.

“Countries must establish an environment that enables citizens and businesses to create, develop and implement new ideas that will allow them to progress and grow. The Global Competitiveness Report helps us understand the drivers of innovation and growth and this edition comes at a time when increasing the ability of countries to adopt innovations is critical to achieving broad-based growth and economic progress,” said Xavier Sala-i-Martin, Professor of Economics at Columbia University.

Sub-Saharan Africa

On average, sub-Saharan Africa’s competitiveness has not changed significantly over the past decade: while a little ground was gained between 2011 and 2015, it has been partially lost again over the past two years. Only four countries (Ethiopia, Senegal, Tanzania, and Uganda) have improved their performance for five consecutive years since 2010. Africa’s recent decline in overall competitiveness is reflected in subdued growth rates – only 1.4 percent in 2016 and a modest 2.6 percent projected for 2017. Gross capital formation is now lower than at any other point in the last 10 years.

Continued deterioration in the macroeconomic environment (Figure 9) is behind most of this year’s fall in competitiveness. Average inflation grew to double digits in 2016 and remains above 10 percent. Public finances are still being affected by past slower global growth and commodity prices, which – although picking up somewhat – remain well below the commodity price levels of the 2005-14 period. As a consequence, African public revenues fell from an average of 26.5 percent of GDP in 2006 to 17 percent in 2016, and many countries are running deficits. In just two years public debt has risen from an average of 31.5 percent to 42.5 percent of GDP, and 22 of the 31 countries assessed by the GCI this year report higher debt than last year.

These challenges are affecting the banking sector, with financial market efficiency continuing to decline. In addition, after four years of improvement, performance in the institutions pillar has worsened this year – particularly in South Africa, Lesotho, and Zambia – while elections in 2017 in Rwanda, Kenya, Liberia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo have increased volatility and uncertainty in the African business environment. These negative trends have been partly compensated by improvements in infrastructure, health, technological readiness, and business sophistication, although Africa remains below the global average in these areas.

There is significant variation across countries. Mauritius is again the most competitive country in Africa, at 45th in the overall GCI, with its main rivals falling back: South Africa drops 14 places to 61st and Rwanda drops seven places to 58th. The most improved African countries year-on-year are Madagascar (121st, up seven), Gambia (117th, up six), Kenya (91st, up five), and Senegal (106th, up six), thanks either to an improved macroeconomic environment (Madagascar and Senegal) or to the efficiency of goods, labor, and financial markets (Gambia, and to a lesser extent Kenya).

In general, restoring macroeconomic stability and institutional trust are short-term priorities to reignite competitiveness and growth in Africa. In the long run, continued investment in infrastructure, human capital, and technological adoption will be needed to reduce productivity gaps.

South Africa (61st) remains one of the most competitive countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and among the region’s most innovative (39th) – but it drops 14 positions in the overall rankings this year. South Africa’s economy is nearly at a standstill, with GDP growth forecast at just 1.0 percent in 2017 and 1.2 percent in 2018 – hit by persistently low international demand for its commodities, while its unemployment rate is currently estimated above 25 percent and rising. Political uncertainty in 2017 has decreased the confidence of South African business leaders: although still relatively good in the African context, the country’s institutional environment (76th), financial markets (44th), and goods market efficiency (54th) are all rated as weaker than last year, also partially due to a structural break in the Executive Opinion Survey sample.

Nigeria (125th) moves up two places in the rankings despite its score having fallen every year since 2012. Its macroeconomic conditions are worsening (122nd, down 14), inflation (131st) is high at 15.7 percent, and its budget deficit (98th) has reached 4.4 percent. Institutions appear more fragile (125th, down seven), adding uncertainty to the business environment. Nigeria is struggling to adapt to lower commodity prices, with the potential for structural change impeded by low scores on infrastructure (132nd), technological readiness (112th, down seven), higher education (116th), and innovation capacity (112th). However, new prudential requirements have strengthened the banking sector’s soundness, and the Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (ERGP) for 2017-2020 contains much-needed reforms on transport and power infrastructure, the business environment, and education investment.