News

United Nations urges end to austerity, calls for ambition to rebalance global economy and achieve prosperity for all

The global economy appears stuck on its path to recovery. A new UNCTAD report, the Trade and Development Report, 2017: Beyond Austerity – Towards a Global New Deal, sets out an ambitious alternative policy route to build more inclusive and caring economies.

Launching the report, UNCTAD Secretary-General Mukhisa Kituyi said, “A combination of too much debt and too little demand at the global level has hampered sustained expansion of the world economy”.

The report states that people should be put before profits, calling for a twenty-first century makeover to offer a global “new deal”. Ending austerity, clamping down on corporate rent seeking and harnessing finance to support job creation and infrastructure investment will be key to such a makeover.

Good times, bad times

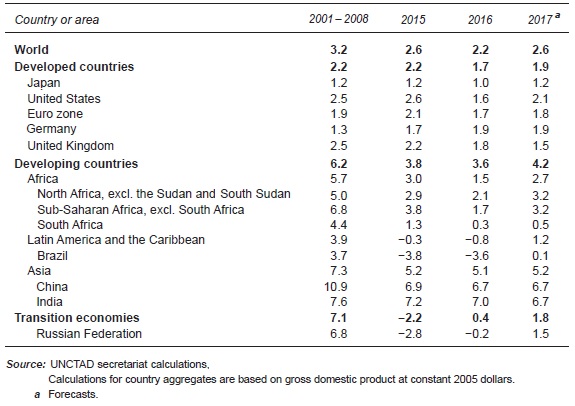

UNCTAD notes that the world economy in 2017 is picking up but not lifting off. Growth is expected to reach 2.6 per cent, slightly higher than in 2016 but well below the pre-financial crisis average of 3.2 per cent. Most regions are set to register small gains, with Latin America exiting recession and posting the biggest turnaround, even if only at 1.2 per cent growth. The eurozone is expected to see its fastest growth since 2010 (1.8 per cent) but is still lagging behind the United States of America (see table).

World output growth: Annual percentage change

The main obstacle to a robust recovery in the advanced economies is fiscal austerity, which remains the default macroeconomic option. According to UNCTAD findings, 13 out of 14 leading advanced economies experienced austerity between 2011 and 2015.

With insufficient global demand, trade remains sluggish. A minor improvement is expected this year, because of a recovery in South-South trade led by China. However, there is much uncertainty, especially with regard to commodities trade, where a brief recovery in prices has not been sustained.

Figure 1: Monthly prices, all commodities

(Index numbers: 2002 = 100)

Source: UNCTAD secretariat.

In the absence of a coordinated expansion led by the advanced economies, sustaining the limited global economic acceleration hinges on lasting improvements in emerging economies. But while most large emerging economies avoided austerity between 2011 and 2015, and China and India have maintained robust growth rates since, they are now facing significant downside risks.

Debt levels continue to rise without real signs of robust growth, and there are concerns about political instability, falling commodity prices, higher interest rates in the United States and a stronger dollar. Capital inflows to developing countries remain negative, albeit less so than in recent years. Furthermore, unforeseen events could knock recovering economies off balance.

Figure 2: Net private capital flow by region, quarterly

(Billions of current dollars)

Source: UNCTAD secretariat.

Age of anxiety: Inequality, indebtedness and instability spell precarious future

In the words of the lead author of the report, Richard Kozul-Wright, “Two of the biggest socioeconomic trends of recent decades have been a debt explosion and the rise of super-elites, loosely identified as the top 1 per cent.” These, the report suggests, are linked through the deregulation of financial markets, to the widening ownership gap of financial assets and a fixation on short-term returns. As such, inequality and instability are hard-wired into hyperglobalization.

The report shows that this makes for a world with insufficient levels of productive investment, precarious jobs and weakening welfare provision. This has become self-perpetuating, with the run-up to a crisis driven by the “great escape” of top incomes, while their aftermath is marked by austerity and stagnating incomes at the bottom.

A decade after sparking a massive global crisis that absorbed trillions of dollars of taxpayers’ money in bailouts, the dominant financial sector has barely changed. Indeed, debt levels are higher than ever. However, the report also examines other sources of anxiety linked to robots and gender discrimination, which are affecting job prospects in developed and developing economies alike. While automation and increased female participation should be welcome developments, they appear threatening because they coincide with a world of austerity and excessive competition, leading to a race to the bottom in job markets.

The result is a popular backlash against a system that is perceived to have become unduly biased in favour of a handful of large corporations, financial institutions and wealthy individuals. The report warns that failure to correct the excesses of hyperglobalization is not only jeopardising social cohesion but diminishing trust in both markets and politicians.

Needed: An alternative to market fundamentalism

The report argues that far too much has been made of trade and technology in explaining the troubles of a hyperglobalizing world. Instead it calls for a serious examination of market power, rent-seeking behaviour and “winner-take-most” rules of the game, which have generated exclusionary outcomes.

The growing concentration of markets is a major issue highlighted in the report, with potentially corrosive consequences for the political system.

As long as policymakers continue to brandish the austerity sword and measure policy success by asset prices and profit levels, big business will dominate in key sectors, and the already significant inequalities may worsen further.

Towards a global new deal: Summoning the spirit of 1947

Moving away from hyperglobalization towards building inclusive economies is not just a matter of making markets work better. It requires a more exacting and encompassing agenda that addresses global and national asymmetries in technological know-how, market power and political influence.

With the United States withdrawing from its role as global consumer of last resort, recycling surpluses is a key element in rebalancing the global economy. The report turns the spotlight on the eurozone – especially Germany – which is now running a large surplus with the rest of the world. The recent Group of 20 proposal made by Germany – a Marshall Plan for Africa – is welcome, but so far lacks the requisite financial muscle. The trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative of China is much bolder, even as its surplus has dropped sharply over the last two years.

The report draws lessons from 1947, when the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the United Nations joined forces to rebalance the post-war global economy, and the Marshall Plan was launched. Seven decades later, an equally ambitious effort is needed to tackle the inequities of hyperglobalization to build inclusive and sustainable economies.

In response to the political slogan of yesteryear – “there is no alternative” – the report outlines a global new deal to build more inclusive and caring economies. This would combine economic recovery with regulatory reforms and redistribution policies, and do so with speed and at the requisite scale. The successes of the New Deal of the 1930s in the United States owed much to its emphasis on counterbalancing powers and giving a voice to weaker groups in society, including consumer groups, workers’ organizations, farmers and the dispossessed poor. This is no less true today.

In today’s integrated global economy, Governments will need to act together for any one country to achieve success. UNCTAD urges them to seize the opportunity offered by the Sustainable Development Goals and put in place a global new deal for the twenty-first century.

There is an alternative

Key measures discussed in the report include the following:

-

Ending austerity with more and better public investment, with a strong caring dimension, including major public works programmes that improve infrastructure and generate employment.

-

Helping to mitigate and adapt to climate change and to promote the technological opportunities offered by the Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

-

Focusing more on care activities.

-

Boosting government revenue (a greater reliance on progressive taxes, including on property and other forms of rent income, can address income inequalities). The report shows that even small changes to the marginal tax rate of the world’s richest cohorts would significantly close funding gaps; tackling tax exemptions and loopholes and corporate abuse of subsidies would greatly add to revenues and fairness.

-

Setting up a new global financial register to record who owns financial assets throughout the world as a first step towards fair taxation.

-

Giving labour a stronger voice (wages need to rise in line with productivity, and work insecurity needs to be corrected through legislative action and active labour market measures).

-

Taming financial capital (appropriate regulation of the financial sector, covering the range from private banking behemoths to “toxic” financial products).

-

Improving capitalization of multilateral and regional development banks (the institutional gap in sovereign debt restructuring needs to be filled at the multilateral level).

-

Reining in corporate rentierism (measures aimed at curtailing restrictive business practices need to be strengthened in tandem with stricter enforcement of existing national disclosure. For example, a global competition observatory could monitor global market concentration trends and patterns and gather information on various existing regulatory frameworks, as a first step towards coordinated international best practice guidelines and policies.)

Regional growth trends

African growth engine back in second gear

Beginning in 2014, lower global oil prices and the end of the commodity boom have affected the African continent (parts of which also suffered a drought) extremely adversely, with growth in the region falling from 3 per cent in 2015 to 1.5 per cent in 2016, and projected to rise to 2.7 per cent in 2017. This masks significant differences in the growth performance of individual countries in 2016, from above 7 per cent in Côte d’Ivoire and Ethiopia, to 1.1 per cent in Morocco and 0.3 per cent in South Africa. In addition, Nigeria saw GDP contracting by 1.5 per cent, while Equatorial Guinea recorded a fall of around 7 per cent.

In the case of many of these economies, their recent predicament is the result of a long-term failure to ensure growth through diversification, and in most case overdependence on one or a very few commodities. An extreme case is Nigeria, one of the largest economies of the African region, where the oil and gas sector accounts for a little more than a third of its GDP and more than 90 per cent of export earnings. The oil price decline dampened demand through its direct effects and indirect effects on government revenues and expenditures, and so was clearly responsible for economic contraction in Nigeria. The recovery in early 2017 is still halting at best. On the other hand, the absence of adequate economic diversification and the consequent dependence on imports has meant that current account deficits have widened, leading to currency depreciation and domestic inflation. So the structure of the Nigerian economy has made it a victim of stagflation driven by current global circumstances. Other economies affected by recent oil price movements include Democratic Republic of the Congo; Equatorial Guinea, where oil accounts for 90 per cent of GDP and is almost the only export earner; and Libya, which derives 95 per cent of its export revenues from oil.

Given the overall high level of commodity-export dependence in African economies, the generalized decline and subsequent low level of commodity prices noted earlier has generated similar outcomes in many other economies. Needless to say, the extent and duration of the price change varied. Non-fuel commodity prices rose 1.7 per cent in 2016 relative to 2015 levels, partly due to the slow recovery in metal and mineral prices, as the deceleration of growth in China led to falls in demand. China accounts for 9 per cent of African merchandise exports and primary commodities account for about 92 per cent of African exports to China. As a result, countries with all kinds of commodity dependence have been affected adversely.

Meanwhile, South Africa fell into a “technical recession”, two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth, with a drop of 0.3 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2016, followed by a drop of 0.7 per cent in the first quarter of 2017.7 This contraction was due to the poor performance of manufacturing and trade, so much so that despite marked production improvements in agriculture and mining, the contraction of the former two sectors could not be neutralized. Clearly internal demand constraints have also played a role here.

All in all, Africa has been hit badly in the current global environment, even though East Africa, led by Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda and United Republic of Tanzania, managed to record respectable growth in 2016.