News

Declining openness a major threat to global competitiveness

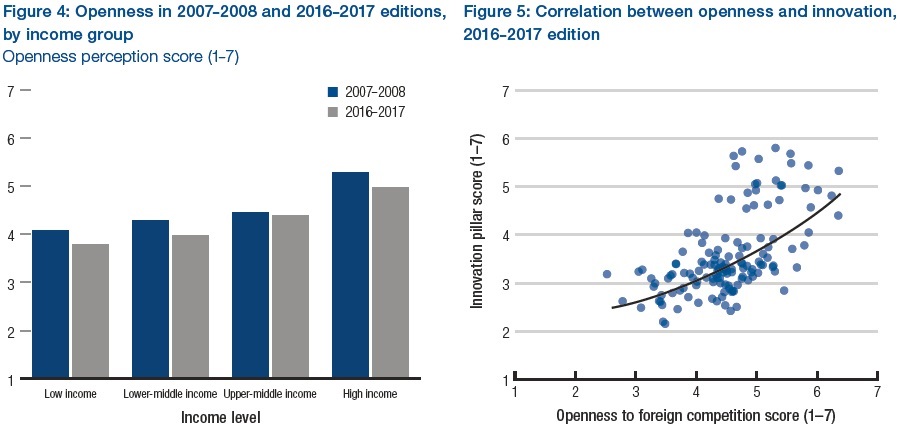

A ten-year decline in the openness of economies at all stages of development poses a risk to countries’ ability to grow and innovate, according to The Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017, which is published today.

The report is an annual assessment of the factors driving productivity and prosperity in 138 countries. The degree to which economies are open to international trade in goods and services is directly linked to both economic growth and a nation’s innovative potential. The trend, which is based on perception data from the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI)’s Executive Opinion Survey, is gradual and attributed mainly to a rise in non-tariff barriers although three other factors are also taken into account; burdensome customs procedures; rules affecting FDI and foreign ownership. It is most keenly felt in the high and upper middle income economies.

“Declining openness in the global economy is harming competitiveness and making it harder for leaders to drive sustainable, inclusive growth,” said Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman, World Economic Forum.

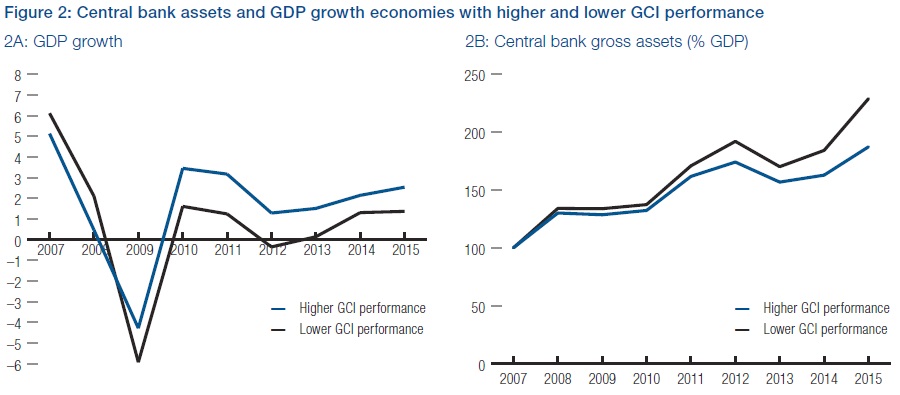

The report also sheds light on why quantitative easing and other monetary policy measures have been insufficient in reigniting long-term growth for the world’s advanced economies. The report finds that interventions by economies with comparatively low GCI scores failed to generate the same effect as those performed in economies with high scores, suggesting that strong underlying competitiveness is a key requirement for successful monetary stimulus.

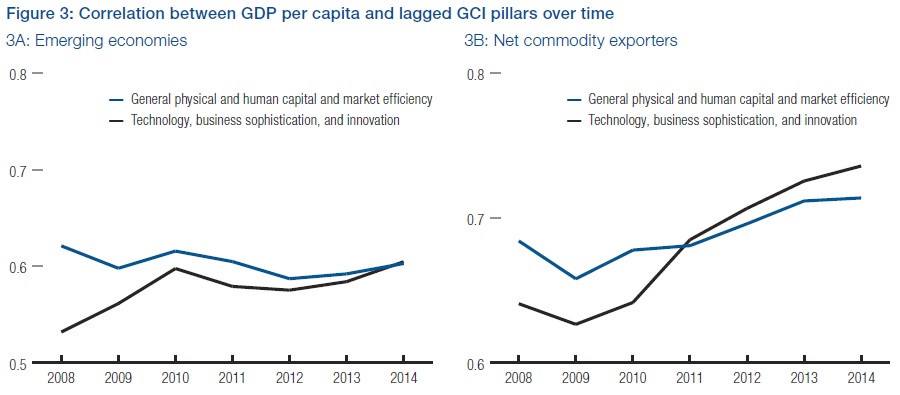

The report offers insight into how priorities may be shifting for nations in earlier stages of development. While basic drivers of competitiveness such as infrastructure, health, education and well-functioning markets will always be important, data in the GCI suggests that a nation’s performance in terms of technological readiness, business sophistication and innovation is now as important in driving competitiveness and growth.

The Global Competitiveness Index in 2016

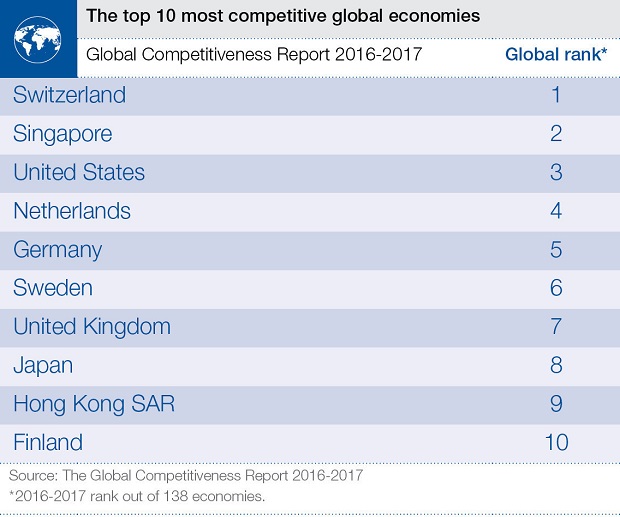

For the eighth consecutive year, Switzerland ranks as the most competitive economy in the world, narrowly ahead of Singapore and the United States. Following them is Netherlands and then Germany. The former has climbed four places in two years. The next two countries, Sweden (6) and the United Kingdom (7) both advance three places, with the latter’s GCI score being based on pre-Brexit data. The remaining three economies in the top ten; Japan (8), Hong Kong SAR (9) and Finland (10) all move backwards.

While European economies continue to dominate the top ten, there remains no end in sight for the region’s persisting north-south divide. Spain improves by one point climbing to 32, however Italy drops back one place to 44 and Greece reverses 5 places to 86. France, the Eurozone’s second largest economy, climbs one place to 21. For all economies in Europe, maintaining and improving prosperity levels will depend heavily on their ability to harness innovation and the talents of their workforces.

There is some sign of convergence in the competitiveness of the world’s largest emerging markets. China, on 28, remains top among the BRICS grouping although another surge by India – which climbs 16 places to 39 – means there is now less of a gap between it and its peers. With both Russia and South Africa moving up two places to 43 and 47 respectively only Brazil is declining, falling six places to 81.

The competitiveness gap in East Asia and Pacific, meanwhile, is widening. Although 13 of the 15 economies covered consecutively since 2007 have been able to improve their GCI score over the past decade, this year sees reversals for some of the larger emerging markets in the region: Malaysia drops out of the top twenty, falling seven places to 25; Thailand drops two to 34; Indonesia falls 4 places to 41 while the Philippines drops ten to 57. A consistent theme for all the region’s developing countries is the need to make inroads into the more complex areas of competitiveness related to business sophistication and innovation if they are to break out of the middle-income trap.

The drop in energy prices has heightened the urgency of advancing competitiveness agendas across the Arab world. With three economies in the top thirty; the United Arab Emirates (16); Qatar (18); and Saudi Arabia (29) there remains a clear need for all energy-exporting nations to further diversify their economies and for much greater effort to improve basic competitiveness among the region’s energy-importing nations.

Two countries in Latin America and the Caribbean make it into this year’s top 50. Chile, the outlier in the region on 33, climbs two places although the gap is closing with the second highest ranked economy, Panama (up 8 places to 42). Next comes Mexico which performs strongly with a 6-point climb to 51. Argentina and Colombia, the third and fourth largest economies in the region, rank 104 and 61 respectively.

One of the most improved nations in sub-Saharan Africa is Rwanda, which rises 6 places to 52. It is closing in on the region’s traditionally most competitive economies, Mauritius and South Africa, although both these countries register more modest improvements, climbing to 45 and 47 respectively. Lower down the ranking, Kenya climbs to 96, Ethiopia holds steady at 109 while Nigeria slips three to 127.

“To me, the interest in economic growth comes from the fact that it is potentially so important for improving human welfare. The Global Competitiveness Report helps us understand the drivers of growth and this edition comes at a time of stalling productivity, the main determinant of future growth,” said Xavier Sala-i-Martin, Professor of Economics at Columbia University.

What is competitiveness?

What is competitiveness? There are actually a number of definitions out there. The World Economic Forum, which has been measuring competitiveness among countries since 1979, defines it as “the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country”. Others are subtly different but all generally use the word “productivity”.

Another way to think about what makes a country competitive is to consider how it actually promotes our well-being. A competitive economy, we believe, is a productive one. And productivity leads to growth, which leads to income levels and hopefully, at the risk of sounding simplistic, improved well-being.

Why should we care about it?

Productivity is important because it has been found to be the main factor driving growth and income levels. And income levels are very closely linked to human welfare. So understanding the factors that allow for this chain of events to occur is very important.

Basically, rising competitiveness means rising prosperity. At the World Economic Forum, we believe that competitive economies are those that are most likely to be able to grow more sustainably and inclusively, meaning more likelihood that everyone in society will benefit from the fruits of economic growth.

How do we measure it?

We break down countries’ competitiveness into 12 distinct areas, or pillars, which we group into three sub-indexes. These are “basic requirements” which comprise institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment and health and primary education. We call these “basic” as these pillars tend to be those that countries at earlier stages of development tackle first.

Next comes our “efficiency enhancers” sub-index. Essentially we’re looking at markets – whether it is the functioning of goods, labour or financial markets – but we also consider higher education and training, and technological readiness, which measures how well economies are prepared for the transition into more advanced, knowledge-based economies.

Our last pillar, innovation and sophistication, consists of two pillars: business sophistication and innovation. These are more complex areas of competitiveness that require an economy to be able to draw on world-class businesses and research establishments, as well as an innovative, supportive government. Countries that score highly in these pillars tend to be advanced economies with high gross domestic product per capita.

What doesn’t competitiveness tell us?

Generally, the world is getting better and better at measuring things, but nonetheless there are always black-spots in any benchmarking exercise. Despite our best efforts, we still haven’t found a fail-safe way of including a country’s environmental record into its competitiveness score. Nor do we attempt to measure whether, or to what degree, competitiveness makes people happy, although there are others that do attempt to measure this. Does a country that is competitive mean it is best able to face the future? Again, the answer is yes and no: some countries are investing for the onset of the Fourth Industrial Revolution in ways that we have not yet found a reliable way of measuring. This last area is a focus of considerable work here these days.

What have we learned this year?

Aside from some countries going up and others going down, this year’s set of data gives us insight into three areas that continue to be important to policy-makers in 2016. With the debate on globalization becoming increasingly politicized, with opponents blaming it for increasing levels of inequality and offshoring of manufacturing jobs, and proponents emphasizing the role it has played in raising millions of people out of poverty, we actually find that countries’ openness when it comes to trading goods and services with one another has been declining steadily, if slowly, for the past 10 years. With openness directly linked to economic growth, this seems significant, especially as the trend seems to stem mainly from the encroachment of non-tariff barriers, which are subtle and often hard to detect.

With every advanced economy having undergone some form of monetary stimulus such as quantitative easing since the great recession, the report also helps us understand why some countries have been more effective than others in reigniting sustained growth. By comparing the competitiveness of those economies that have engaged in monetary stimulus programmes over this period, we find that those with high competitiveness scores were more successful in driving economic growth than others with lower scores, even if the latter have expanded their central bank balance sheets by a greater amount.

The report offers insight into how priorities may be shifting for nations in earlier stages of development. While basic drivers of competitiveness such as infrastructure, health, education and well-functioning markets will always be important, data in the report suggests that a nation’s performance in terms of technological readiness, business sophistication and innovation is now as important in driving competitiveness and growth. This is important for policy-makers and leaders in emerging markets who need to be aware that the reality when it comes to helping move their economy up the income ladder is much more nuanced than they may have previously believed.

» Download: The Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017 (PDF, 5.99 MB)