News

Global trade slowdown, Brexit, and the trade implications for Commonwealth developing countries

Global Trade Slowdown, Brexit and SDGs: Issues and Way Forward

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) outlined in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by the international community in September 2015, is a global framework of actions over the next 15 years to tackle critical socioeconomic challenges faced by developing countries. Through its 17 goals linked to 169 targets, the progress of which is to be measured by as many as 304 proposed indicators, the SDGs aim to eliminate extreme poverty, combat inequalities, promote prosperity and strengthen global partnerships while protecting the environment. Building on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) initiative implemented during 2000-15, this new global architecture seeks to finish what the MDGs started. However, the SDGs go much beyond in clearly identifying the tools, or ‘means of implementation’, for meeting the targets.

Unlike its predecessor, the 2030 Agenda provides an elaborate role – both direct as well as crosscutting – for international trade for achieving many of the specific SDGs and targets. Indeed, trade has been directly referenced nine times in the seventeen SDGs compared to just once in the MDGs. This heartening effort of mainstreaming trade in a global development strategy has, however, come at a rather inauspicious time.

More than eight years after the global financial crisis of 2008, the world economy is still struggling to return to its pre-crisis growth trajectory. The growth of world trade has also been depressingly sluggish for several years now amid the feeble economic performance of the euro-zone, growth slowdown in China, lower commodity prices and a stronger US dollar – all having adverse implications for developing countries’ trade expansion. The failure to conclude the long-running Doha Round of multilateral trade negotiations contributing to the proliferation of regional trading arrangements has also placed the global trading system at a crossroads.

Furthermore, the decision of British voters in a referendum on 23 June 2016 to leave the European Union (EU), termed ‘Brexit’, presents an additional shock to the system. The uncertainties caused by Brexit may weaken the prospects for world economic recovery, with severe implications for developing countries and Least Developed Countries (LDCs). Since trade is to play a major role in the SDG framework, the outlook for promoting trade-led economic growth and sustainable development may become more challenging.

This issue of Commonwealth Trade Hot Topics provides some perspectives on how the current global economic environment, including the possible impact of Brexit, bear upon the effectiveness of trade in achieving the SDGs, and what can be done to address this challenge.

Post-Brexit trade and development implications

The UK is the world’s fifth largest economy generating trade flows of US$1.6 trillion (almost 4 per cent of total world trade in goods and services in 2015). While the UK’s total goods trade within the EU has remained relatively unchanged over two decades, the UK has steadily diversified its trade with developing economies, especially China. Developing countries now account for about 25 per cent of the UK’s total goods trade – approximately US$300 billion.

Owing to strong historical ties, the UK is an important export destination for many African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries. However, these countries have not been able to substantially grow their exports to the UK due to various capacity constraints. This is most evident in the case of CARICOM, where the share of total trade with the UK has contracted, notwithstanding the implementation of the EU-CARIFORUM Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA). There is, however, a bright side as well. Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries have almost doubled their merchandise exports to the UK over the period 2000-14, from US$8 billion to approximately US$16 billion, while LDC exports have grown about fivefold over the same period, from US$1.58 billion to about US$7.84 billion. Almost 70 per cent of UK goods imports from LDCs are consumer goods, such as textiles and garments, supporting industrial capacity in these poorest nations. Although the information on services trade is not readily available, it is a matter of fact that the UK has been one of the most important drivers of services exports for many tourism-dependent ACP countries. Remittances from the UK are also quite high for several ACP countries.

Given the UK’s significant participation in world trade, the economic fallout from Brexit will have major implications for developing countries. The transmission channels whereby developing countries will be impacted include trade, investment, remittances, aid and development finance, the performance of the UK economy, and the UK’s global influence on trade and development issues. For example, as the pound depreciates by more than 10 per cent, ACP countries stand to lose purchasing power of their export receipts, remittances and aid resources close to US$2 billion. Over the medium to long term the repercussions through these channels will be determined by the nature of trade deals the UK can secure with the EU and trading arrangements with ACP countries.

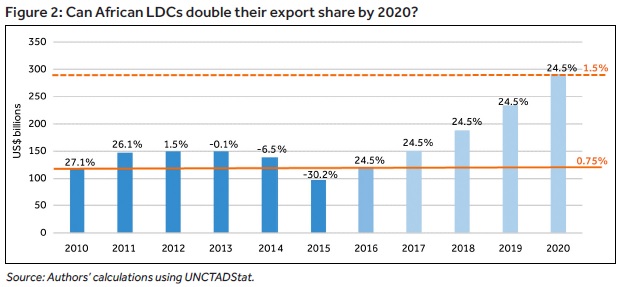

Therefore, along with prolonged subdued global trade and growth, Brexit-related uncertainties can further weaken global economic prospects, undermining the achievement of the SDGs. To illustrate with one specific example, consider SDG 17, target 11: doubling the share of LDC exports by 2020 (first agreed in the Istanbul Programme of Action and since adopted as SDG 17.11).

The total exports from African LDCs in 2010 were US$116.7 billion, accounting for 0.76 per cent of global exports. While these economies recorded strong export growth until 2011, export performance has since been dismal owing to falling commodity prices and other reasons mentioned above. By 2015, African LDC exports had contracted to US$97.5 billion, with their combined share in global exports shrinking to 0.59 per cent.

Even under the current weak state of trading activities, if the global trade continues to grow at 3 per cent per annum, African LDCs will have to record annual export growth of about 25 per cent to meet this SDG target. This appears to be a bleak prospect given these countries’ recent export performance.

Trade Implications of Brexit for Commonwealth Developing Countries

This issue of Commonwealth Trade Hot Topics analyses ‘Brexit’ – the UK’s departure from the European Union (EU) – and shows that the effects for some Commonwealth countries may be severe unless specific actions are taken to avoid this. Yet there is a danger of Commonwealth interests being ‘crowded out’. Most member countries will have no representation in the decisions that could affect their trade, being able to influence events only from the side-lines in an environment where there exists severe time pressure and great uncertainty over almost all features of the Brexit process.

Brexit will affect the rest of the world along several direct and indirect pathways. If the UK or EU economies slow, so may their import growth. The UK will create a new trade policy and its departure may provoke changes in the impact of the EU-27’s regimes. Any reduction in investment as a consequence of short-term uncertainty or longer-term de-integration of the single European market will have possible adverse effects on growth and trade. Then there are indirect effects through the impact on investment and exchange rates, migrant remittances and global growth.

The trade policy effect

This Hot Topic focuses on what may be the most visible and, for some Commonwealth countries, potentially the most dramatic Brexit effect: changes to UK trade policy. The challenge is to ensure that the exports of Commonwealth countries are not disrupted immediately following Brexit and, more ambitiously, to use the UK’s new-found policy discretion to fashion a trade regime that is better at supporting development than the status quo.

There will be trade policy effects in three arenas:

-

the UK and its current EU partners (including two Commonwealth countries);

-

the UK and those states that currently have favoured access to the EU market;

-

possible trade agreements between a post-Brexit UK and countries such as China, India and USA with which the EU does not have a trade agreement.

All of these are related, but the second is perhaps the most urgent for those Commonwealth developing countries that have ‘better-than-Most Favoured Nation (MFN)’ access to the EU market under either an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) or other type of Free Trade Agreement (FTA), or through trade preferences. One point on which there appears to be legal consensus is that unless specific actions are taken to avoid this outcome the trade regime of the EU will cease to apply to imports into the UK on Brexit+1.

EU border measures will be replaced by those of the UK – but these are yet to be created. Negotiations within the World Trade Organization (WTO) will be needed to dissect the EU’s commitments into a set applying to the UK and another set for the remaining members. But they are unlikely to be concluded by Brexit+1, given that creating a completely new MFN regime for goods and services would be a hugely complex and time-consuming task.

The only reasonable working assumption is that the Brexit+1 default option – if nothing better is put in place – is that the UK’s MFN regime will be the same as, or very similar to, current EU policy. This would affect seriously some Commonwealth developing countries. To flag the scale and incidence of the impact we have analysed all UK imports from each vulnerable Commonwealth trade partner and, where this is possible, calculated whether they would face a tariff hike.

It is easier to list the Commonwealth countries that will not be affected significantly by Brexit than those that will. Based on average annual EU imports in 2013-15, only 12 of the Commonwealth developing countries face a potential calculable tax hike representing less than 1 per cent of the UK’s total imports from them.

How big a hit? A simple indication is €715 million. This is the ‘new tax’ that would be levied on UK imports from the Commonwealth from (calculable) tariffs that are higher than today’s. It is a broad guide only, taking account of the precise calculation issues. How could this outcome be avoided? Four stylised options (each with scope for many nuances) cover the ground.