News

Brexit: impact on developing countries

In a surprise outcome for many in Europe and beyond, British people have voted to leave the European Union.

The macroeconomic implications of this decision are already being felt, not the least by emerging and developing countries. Global stock markets have been hit by around a $2 trillion loss and risk aversion has set in, exposing developing markets to volatility without much liquidity to absorb the shock. Already, countries for whom Britain is a significant market are seeing their currencies weaken or borrowing costs rise.

What are the ramifications of an impending Brexit for developing nations and their economies? How can the UK exit the EU in such a way that does not undermine global economic development? And what opportunities might this hold for deeper cooperation within such existing alliances as the G20 and the Commonwealth?

On 7 July 2016, the ODI hosted an expert panel consisting of Kevin Watkins, Executive Director, ODI (Chair); David Luke, Coordinator of the African Trade Policy Centre, UNECA; Vicky Pryce, Economist and former Joint Head, UK Government Economics Service; Mohammad Razzaque, Adviser and Head of the International Trade and Regional Cooperation Section, Commonwealth Secretariat; and Phyllis Papadavid, Team Leader in International Macroeconomics, ODI to explore some of these issues. Watch the video stream below.

Brexit: Africa’s trade and development implications

Extracts from the Speaking Notes for Mr. David Luke

Brexit has thrown up uncertainties in many areas relevant to development; the most pertinent to Africa’s trade and development cooperation that I would like to identify are:

-

The impact on the UK economy

-

The UK’s formal trade arrangements

-

Brexit lessons for African integration, and

-

The UK’s trade and development assistance

Brexit will present the UK with many challenges and it is clear that these will spill-over into impacting Africa and beyond. Such challenges may manifest through different channels: those which I have focussed on here are trade and trade-related development assistance. These are significant points of the relationship between the UK and Africa, and going forward we must ensure that all opportunities to set a development-friendly and conducive trading environment between these partners are sought. Key amongst this will be the development of a comprehensive continental trade arrangement between Africa and the UK, as well as continuing the UK’s excellent support in Aid for Trade.

The UK’s formal trade arrangements

When the UK joined the European Economic Community 43 years ago it transferred all authority for its trade agreements to the Community. In 2014, much of the UK’s 1.1 trillion dollars in trade was channelled through these clear and predictable legal and institutional frameworks.

The EU has FTAs inforce with 96 ountries representing more than a third of world GDP. Early WTO announcements have been made for FTAs with a further 35 countries, worth another 38% of world GDP. Once concluded the EU would have FTAs with 131 countries representing about 70% of world GDP. And at least another 20 countries are involved in EU trade negotiations which have not yet been given early WTO announcements.

The EU also offers its Everything But Arms (EBA) to Least Developed Countries and a Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) arrangement to further Developing Countries.

As for Africa, as well as the Caribbean and Pacific, the UK’s formal trade relationships were set to have been secured within the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) between the EU and regional country groupings, including West Africa, Central Africa, the East African Community, Eastern and Southern Africa, the South African Development Community, the Caribbean, and the Pacific.

Most of the EPAs, which the UK fought hard to conclude, are in the process of being signed following more than a decade of negotiations between the EU and the respective country blocs. They mark the evolution of trading arrangements between these countries which have developed from the Lome Conventions beginning in 1975 and the Cotonou Agreement in 2000.

It is notable that a centrepiece of the Brexit campaign was to reassert stronger trading relationships with its Commonwealth countries. Yet even if the UK can prioritise such negotiations, the UK will be unable to secure arrangements preferable to the EU due to an EPA clause which requires the EPA countries to also share with the EU any preferable conditions granted in other agreements.

The UK will now need to re-consider the post-Brexit alternatives to the approximately 151 countries with which the EU now has, or is currently negotiating, trade agreements, including the EPAs, as well as its place within the WTO.

Continental Approach to a Comprehensive African Trade Agreement

The UK should consider a continental approach to Africa. The goal should be for a comprehensive single trade agreement with all 54 countries that incorporates limited reciprocity, immediate access to the UK market, and phased-in access to the African market. This would be similar to the EU’s EPAs, which would likely form the basis for discussions.

A single continental approach would reduce the multiplicity of new arrangements the UK would have to negotiate while also being aligned with Africa’s plans for continental regional integration plan as per Africa’s Agenda 2063.

Such an Agreement could learn from the best practices of other development-oriented trade agreements as well as the experience of the EPA negotiations. It should, for instance, consider aspects such as:

-

The environment and climate change, and in particular facilitating green technology transfer;

-

Removing subsidies to ensure that Britain competes fairly with the African agriculture sector;

-

Include partnerships in services to help African countries learn from the UK and build capacity.

Such an agreement could potentially form the model for how the US engages with Africa after AGOA, and even for the rapidly developing emerging markets with increasing interest in Africa.

The UK has the opportunity to set a high standard for developed-oriented trade agreement with Africa.

African Initiative

African governments should themselves be proactive in approaching the UK re-negotiations. Indeed Mauritius has already set up a Ministerial Committee to look into the repercussions of Brexit. That the UK does not yet have its own plans in this respect leaves a gap for African initiative. This is especially pressing given the amount of urgent negotiating priorities which Britain faces; Africa will not be at the top of the list, and African countries will need to press for their place. As such African countries should take the initiative and start developing proposals for early talks with London.

The same will certainly apply to the Caribbean countries, who while notionally trading with the EU, actually send most of their exports to the UK. Yet as a collection of especially small markets will need to fight for a place amongst British negotiating priorities.

Taking the initiative can help these countries press for more development-friendly opportunities including:

-

The UK’s withdrawal from the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy, which subsidizes European farmers at the detriment of Africa’s agricultural output.

-

And opportunities will be present to relax technical-barriers to trade, which protect some in the EU market, and especially southern European producers, from products in which Africa has a comparative advantage, such as tropical fruits and vegetables, and meats.

Indeed, the South African Citrus Growers Association has already suggested that revised UK plant health regulations on citrus imports could be easier to comply with than present EU regulations.

Similar benefits could be arranged for beef, of which African exports to the EU have fallen following compulsory and expensive regulations, such as those to prevent Mad Cow, which are applied to African countries in which Mad Cow has never been diagnosed.

Transitional Trade Arrangements

Transitional trade arrangements will however be required while such a continental agreement is arranged. The UK will have many negotiating priorities during Brexit and such transitional arrangements must bridge the gap to a more comprehensive and progressive trade agreement, which is likely to take more time.

One suggestion is for the UK to ratify and begin implementing concluded EPA agreements prior to activating Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which will start the stopwatch on the 2 year process through which the UK leaves the EU. Up until the final moment, the UK remains part of the EU and is bound by EU law.

Another is that the UK works through the scope of Article 50 to incorporate transitional arrangements itself for leaving EU Agreements such as the EPAs. Article 50 does not define the scope and content of the withdrawal arrangements, and so it is feasible that the UK could negotiate to retain transitional membership of certain Agreements in some way.

Alternatively, a standstill may be necessary on EPA implementation with the EU more broadly. This may be required pending clarification of EU and UK future trade relations with third countries.

Brexit and development: how will developing countries be affected?

On 23 June 2016, the UK voted to leave the European Union (EU) after 43 years of membership. Whether or not the UK eventually leaves the EU, the economic fall-out is already considerable, including the fall-out for developing countries.

This briefing discusses the actual and potential economic impact of Brexit on developing countries. Brexit will have major implications for developing countries, whether or not the UK actually leaves the EU. Different countries will be affected in different ways, depending on how the UK exits. There are mostly negative effects for developing countries, but some positive ones too:

-

In the short-term, the threat of Brexit has led to currency and stock market fluctuations, which have not spared emerging markets and poorer countries.

-

The long-term effects depend on UK trade deals, any changes to aid allocation, new global collaborations, financial markets and the way in which migration and remittances are maintained.

Policies at various levels can help to mitigate the shock or mitigate the impact of the shock.

Brexit and developing countries: pathways of impact

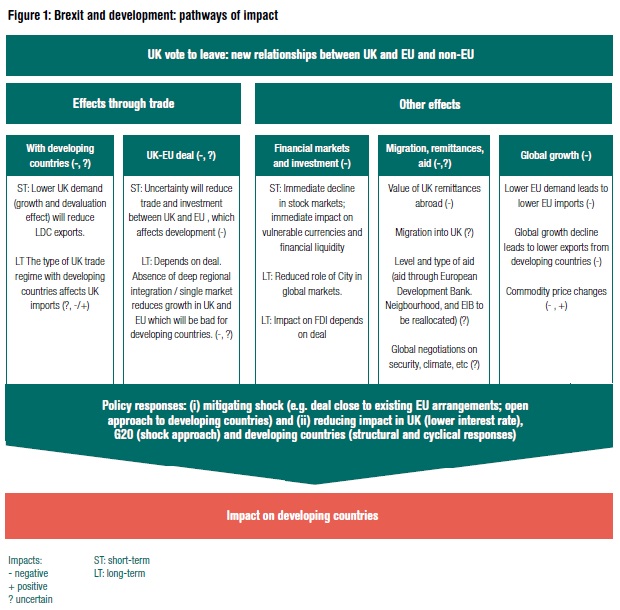

The impact of Brexit on developing counties depends on the shock and the transmission channels of that shock. The first element we consider is the shock – the shock of both the vote to leave the EU, and the policy of actually leaving. Secondly, we consider the potential effects of the Brexit shock on developing countries, which countries might be affected, and why. Figure 1 lays out the following pathways of impact:

-

Trade: a lower value of the pound and lower UK growth will reduce imports in the short-term. Least developed countries (LDCs) as a group would see their exports decline by 0.6% (or $500 million). The most acutely affected countries will be those that export in relative terms a lot to the UK, such as Bangladesh, Kenya, Mauritius and Fiji. In the long-term, the trade effects will be on the types of deal between the UK and the EU, and between the UK and developing countries. There will be separate issues for deals on goods trade and on services trade.

-

Financial markets and investment: there have already been weaknesses in currencies and stock markets of affected countries (global equities are 2% lower than on 24 June; on 5 July the pound was 12% lower, while currencies in emerging markets had already devalued by 4-6%). In the long-term, there might be effects through lower FDI flows because of smaller GDP, and financial sector activity may be relocated to the EU and elsewhere.

-

Migration and remittances: while the outlook for immigration appears negative, we cannot rule out that migration might actually increase. Lower immigration into the UK will mean less UK growth which will affect development negatively. In addition, the development effects through UK remittances are undoubtedly negative because of the 10% devaluation of the pound. The countries most dependent on UK remittances include LDCs such as Uganda, and other countries such as Kenya, Mauritius, South Africa, Nigeria, St Lucia, India, etc. The loss would be equivalent to $1.4 billion of spending in developing countries, which includes a $370 million loss in both Nigeria and India (data on the value of bilateral remittances from the World Bank).

-

Aid, development finance and global collaboration: a reallocation of aid away from EU channels (around 10% of UK aid) and through non-EU channels has yet unidentified implications. Commonwealth countries such as small and vulnerable middle income countries might become the new beneficiaries, but we cannot be sure as aid through EU pooled instruments might still be an option where it remains effective. For example, we have previously argued that pooled EU aid or trade has been effective (Holland and te Velde, 2012). More significantly, UK aid was $18.7 billion in 2015 (OECD DAC data), which will now decline in value by at least 10% because of devaluation of the pound. In other words, this amounts to a loss of $1.87 billion in value of UK aid. Other development finance channels such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) will also be affected. The UK is the biggest investor in the Juncker investment plan and holds 16% of the EIB’s capital. If the UK leaves the EIB, it will not have a public investment bank, becoming an outlier in G20 terms. Moreover, it would have no say on how the EIB invests in developing countries (around 10% of total EIB investments) and volumes of investment in poor countries may drop. It is also not yet clear how global negotiations on issues like climate and security will be affected. Can the EU maintain an influence on climate negotiations that may benefit the poorest countries? The EU may face a unknown period of disintegration, instability and rebranding. On the other hand, there may be a strengthening in the fight for the global ideals the UK and the EU stand for: human rights, justice, equality, free trade and investment and open societies, but this is not guaranteed. The UK would need to seek new alliances (e.g. G20, Commonwealth, UN) in promoting the provision of global public goods that cannot be served by EU structures alone.

Figure 1 introduces a number of policy areas, which are important when determining the ultimate impact on developing countries:

The impact on trade with developing countries

The UK alone takes around 5% of LDC exports. The effects of Brexit on trade will vary by country. However, the effects may be particularly important for some countries. For Belize, exports to the UK is 30% of total exports; for Mauritius and Fiji, it is 20%; and for Bangladesh and Kenya, it is 10%.

While the UK may not represent an important destination for all developing countries, the impact of Brexit is yet another negative trade effect affecting developing countries after the fall in commodity prices, the slowdown of emerging economies such as China, and increased protectionism in G20 countries. Again, there are short and long-term trade effects.

Short-term effects on trade

Brexit has increased uncertainty in the UK economy. UK economic policy has not changed, apart from the interventions to stabilise markets associated with the shock, and abandoning the objective of achieving balanced budgets. However, the potential long-term effects of Brexit in terms of structural adjustment in the UK economy (i.e. contraction of the services sector) has generated immediate instability. The fall in the pound translates into a decrease in UK wealth (lower price of assets including housing), with uncertainty reducing investment and increasing income insecurity. The combination of a negative wealth effect, the fall in incomes and the changes in expectations will depress UK aggregate demand. Imports will be directly affected, and will fall as a result of the negative income and expectations effects, and as a direct result of the fall in the pound. Imports, regardless of the origin, after Brexit have therefore become more expensive. This negative effect is expected to affect trade immediately.

-

Effects on developing country exports to the UK

The structure of the UK economy is heavily oriented towards the provision of services and the production of high-tech intermediates to regional value chains. The UK does not import large amounts of raw materials from LDCs. Rather, the UK is a major importer of final or consumer goods. Almost 70% of the UK goods imports from LDCs are consumer goods such as garments.

We expect that imported products from developing countries, such as basic food staples will not be substantially affected as they are less price sensitive (e.g. tea and beans from Kenya or tea from Malawi). However, demand for imported goods that are more sensitive to income and price changes is expected to be harder hit. Flowers, certain gourmet foods (i.e. high quality coffee) and garments will be affected. Durable consumer goods such as toys, bicycles and other light manufactures are also likely to be affected substantially. This suggests that those countries that export price sensitive goods to the UK are expected to see a drop in their exports. For example, Bangladesh and Cambodia in textiles and garments, and Kenya in flowers, will be among the countries most directly affected. The observed fall in the pound and the forecast effect of Brexit on GDP (3% within 18 months) sheds some light on the effect on exports in LDCs. The fall in the pound will create a total fall in exports in LDCs by roughly $370 million (value of exports multiplied by the change in the pound). While the fall in UK economic activity will cost LDCs around $111 million in exports. Together, we therefore suggest that the cost in terms of LDC exports will be closer to $500 million, or 0.6% of LDC exports. This does not include the price and income effect coming from the rest of the EU. Consequently, this actually presents a conservative estimation of the short-term trade effect.

-

Effects on EU exports to the UK

Brexit may affect important UK trade partners, including other EU countries that will be negatively affected in their demand from the UK; while countries such as Ireland, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany may also be affected. Around 7% of EU exports goes to the UK. Assuming a unit elasticity of demand, the effect of the fall in the pound by 10% should reduce EU wide exports by 0.7%.

-

Effects on EU imports from developing countries

The euro has fallen in relation to the US dollar in the last week (around 2%) making EU imports more expensive. Consequently, exporters of non-basic consumer goods from developing countries to other EU member states may also be hit. For example, Ethiopia may be affected in its exports of flowers to the EU. The UK and the EU represent 30% of the LDCs exports and for some countries such as Bangladesh, they represent above 50% of their total exports.

-

European supply chain effects and developing countries

The UK and EU are linked through European supply chains (trade and investment) where components and intermediates products are traded, forming a big ‘European factory’. It is likely that there will be disruption in these value chains. The fall in the pound may generate adjustments that could affect developing countries, particularly those providers of raw or semi-processed materials such as those like South African vehicle-parts being exported to the EU. The effects on these value chains will be larger in the long-term, once the trade policy implications of Brexit become effective or at least known.

Long-term effects on trade

The long-term effects of Brexit will depend on a newly defined UK trade policy. This is determined by the kind of economic and trade relationship that the UK will eventually establish with the EU and the rest of the world. Some 43% and 33% of UK goods and services exports, respectively, are exported to the EU. The trade effects will depend on two changes: the trade policy that the UK will apply after leaving the EU, and the ultimate UK economic structure after the agreement is finalised with the EU.

The effects on developing countries from the type of relationship the UK will have with the EU will depend on three potential outcomes:

-

The UK retains access to the EU single market

-

The UK maintains a customs union with the EU

-

The UK adopts its own trade policy in line with WTO principles.

UK, EU single market and developing countries

The continuity of access to the EU single market may be key in determining both dimensions. If the UK remains part of the single market (this would mean joining the European Economic Area), the structure of the import demand of the UK from developing countries is unlikely to change significantly. The UK will continue to take part in European value chains and its services sector will keep its access to the EU market. Consequently, very little will change in terms of the structure of the UK economy, and consequently its import demand.

In addition, if the UK remains part of a customs union with the EU, there will be no changes in terms of tariffs and preferences applied by the UK to the rest of the world. The continuation of the preference margins in developing countries’ access to the UK will, despite the short-term negative effects explained, secure that demand will recover and major structural adjustments will not be necessary in the affected developing countries.

The situation will be different if the UK does not maintain its access to the EU single market. This will imply a major adjustment in the UK economy. The services sector is likely to contract and the participation in regional value chains will be severely affected. Consequently, the UK will adopt a different production and trade structure. The loss of access to the single market may imply changes in UK consumption patterns as well. These will constitute large challenges, but also opportunities for developing countries.

One outcome is the possible divergence in product standards. Developing countries will find that instead of supplying a single European value chain, they will be in the position of supplying two different markets. Standards and regulations may start to differ between them and developing countries will find that their compliance cost will increase. Moreover, the supply relationships established with European-wide retailers may be affected. As a result, some adjustment in the trade patterns of developing countries may be necessary.

At the same time, new opportunities may be created. The UK may substitute away the products previously sourced within the EU, which could present an opportunity for developing countries. However, it is worth considering that in the case of agricultural products, it is likely that large developing countries (Argentina, Brazil) or other developed countries (US, Canada, Australia) will be the main beneficiaries. LDCs are not expected to benefit substantially.

A new UK trade policy

Depending on the agreement that the UK may reach with the EU, we can identify two scenarios:

i. UK-EU customs union

Here we assume that the UK does not have access to the single market but mantains a customs union with the EU. This would imply a scenario similar to the trade relationship between Turkey and the EU. Although still speculative, under this scenario the UK would maintain the same Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariffs and preferences that are currently applied by the EU. This would be less disruptive for trade with developing countries. However, again it should be noted that there might still be some implications with respect to the cumulation of rules of origin, which are unclear at this stage. In this scenario, although the structure of the UK economy might change as a result of the lack of access to the single market, tariff and preferences would not be affected in principle.

It is very important to highlight that if the UK remains in a customs union with the EU, the need for and the complications of renegotiating over 50 free trade agreements (FTAs) that the EU has negotiated, will be smaller. Although some renegotiation may be necessary, the liberalisation schedules will remain. For example, in terms of market access, the UK could continue to offer duty free under the same conditions as under current Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs). However, African, Caribbean and Pacific states countries (ACP), by virtue of the MFN clause under EPAs, would not extend additional concessions to the UK.

ii. Autonomous trade policy

A further scenario is that the UK would apply its own trade policy. This means that, although the UK may maintain a free trade area with the EU, its trade policy will be independent. The UK will need to define a new MFN tariff and its own system of preferences. The level and structure of MFN tariffs will depend on whatever is conceded in the very complicated negotiations with the rest of the World Trade Organization (WTO) members. In this case, there are also several implications for developing countries, and there may also be opportunities. It is unclear what the MFN tariffs would be. Based on suggestions of some Brexiters (e.g. Minford, 2016) and on the pre-EU trade policy, the UK may apply very low (even zero) MFN tariffs. This will facilitate the negotiations with WTO partners but will complicate the negotiation of future FTAs and the renegotiation of the existing ones. The UK would lose the tariff bargain chip i.e. the UK would not be able to negotiate lower tariffs abroad by lowering UK tariffs.

However, while several countries will gain from lower tariffs, there will be a loss of preference margins for preference-dependent developing countries, such as the Everything But Arms (EBA), ACP, and the GSP countries. In a scenario where the UK applies zero tariffs, preferences no longer exist. Developing countries, particularly LDCs dependent on the existence of positive preference margins may struggle to compete with other efficient producers.

In this zero tariff scenario, only efficient suppliers will manage to continue exporting to the UK. Only the lowest priced suppliers will be able to compete, as the preference margins that offset high production and trade costs previously would now disappear. The quality and competitiveness of soft (e.g. regulatory issues) and hard (physical) infrastructure in the poorest countries will become even more important as countries can no longer rely on preference margins to offset the deficiencies in infrastructure. On the other hand there will also be opportunities for developing countries as a whole if the UK’s new trade policy is more welcoming to imports from developing countries through better rules of origin, better preferences in services and more targeted Aid for Trade that improves infrastructure and reduces the costs of trade.