Blog

Moving Up the Value Chain – How Can Africa Keep Climbing the Ladder?

In the standard model of world trade, which is taught to first year students around the world, the patterns of world trade are fixed and unchangeable. Ricardo’s classic model of comparative advantage has one nation as a cloth exporter and another nation as a wheat exporter, and there is reciprocal mutually-advantageous trade between these nations. This basic pattern predominates in trade theory, even though the theoretical constructs may have evolved over time with new theoretical breakthroughs.

On the other hand, the process of industrialisation that the developed countries of the world have gone through suggests that trade patterns can and do change fundamentally. If the UK was a cloth production specialist in the 1800s, it is very far from this pattern today – being an exporter of services and technology products. The fundamentals that explain the export specialisation of a group of countries at a particular time are subject to change, implying that the theory of comparative advantage – the basic premise of trade – is a good static but not dynamic explanation for trade.

In fact, the bulk of global trade today (about 70%) is not even in finished products, but in intermediate products: items that are used in the further manufacture of products or the repair of existing products[i]. Most of these trade flows therefore represent global value chain (GVC) trade, where transnational corporations (TNCs) own production processes spanning multiple countries and covering the full spectrum of production: design, research & development, production, business support, marketing and customer support. While some of the parts of this chain are owned by the same TNCs, in some cases parts of the value chain have been outsourced to third parties who transact with the TNCs at arm’s length.

In the same way that basic static trade patterns are explained by comparative advantage principles (relative competitiveness), trade patterns in value chain trade are also explained by these same patterns of relative competitiveness. TNCs that govern GVCs have distributed production processes according to these patterns, for example – a smartphone is designed and has its software innovated in the United States – a technologically advantaged country – and has its physical production completed in Vietnam – a labour-cost competitive country.

It is the nature of value generation that the more sophisticated aspects of production – research, development, software development and business support – attract the lion’s share of the value returned to producers and therefore allow faster capital accumulation. The progression towards these sophisticated roles in production is called ‘upgrading’ and is (or should be) the end goal of industrialisation in a value chains context.

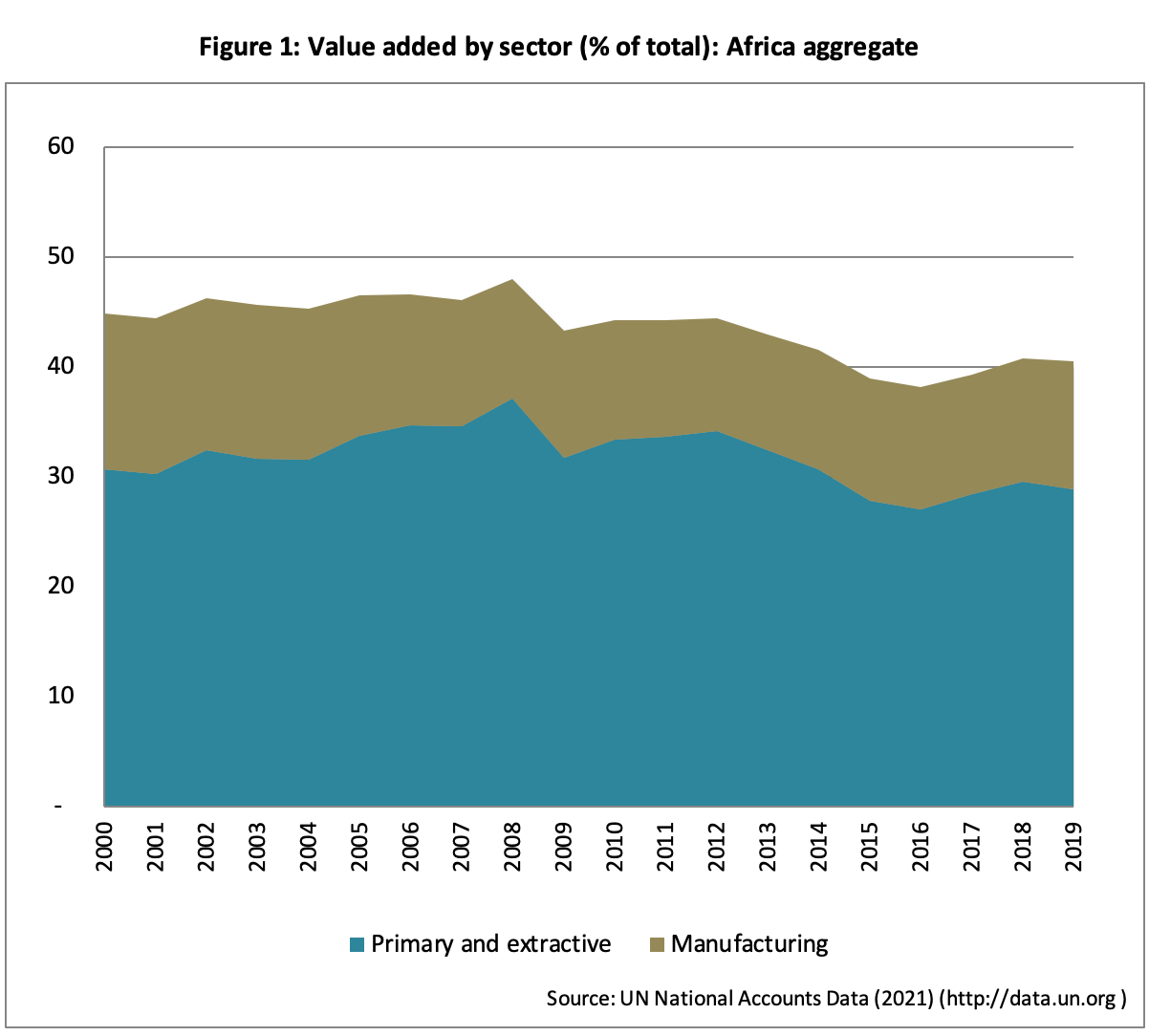

The question is; what is Africa’s role in global value chains and what are the prospects for its production to be upgraded? This question is important for a variety of reasons. Many African countries have been going through a process called premature deindustrialisation[ii], where the manufacturing value content of total output goes into gradual decline before the country is fully industrialised (hence the ‘premature’ reference). Instead, the content of output in many African countries remains dominated by primary output (agriculture, fuels and minerals) as well as an increasing share of services such as finance and telecommunications.

Figure 1 visualises premature deindustrialisation in Africa by plotting the value added content of total production for manufacturing (upper region) against that for primary production (lower region).

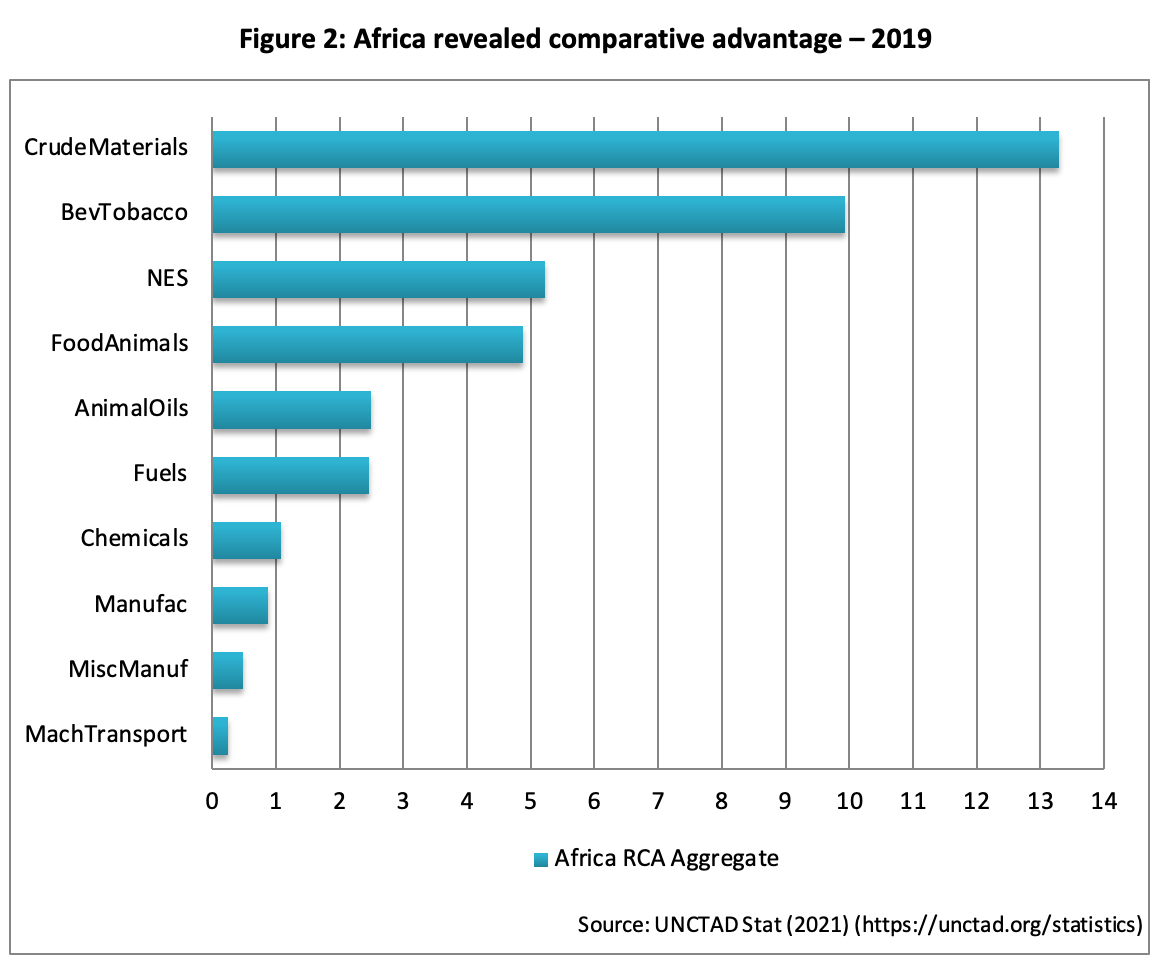

This phenomenon of premature deindustrialisation is not hard to understand when one looks at the data for Africa’s trade competitiveness. ‘Revealed comparative advantage’ (RCA) is a measure of the extent to which a country’s export patterns outperforms the global aggregate. It is an index where the score of one equals the global aggregate (i.e. no revealed advantage), above one is a revealed advantage (i.e. globally competitive) and less than one shows underperformance relative to the global aggregate.

All of Africa’s competitiveness is clearly in primary production (‘NES’ means gold and investment coin such as Kruger Rands). The types of production that represent ‘upgrading’ in the value chain – manufactured products – all score less than one[iii].

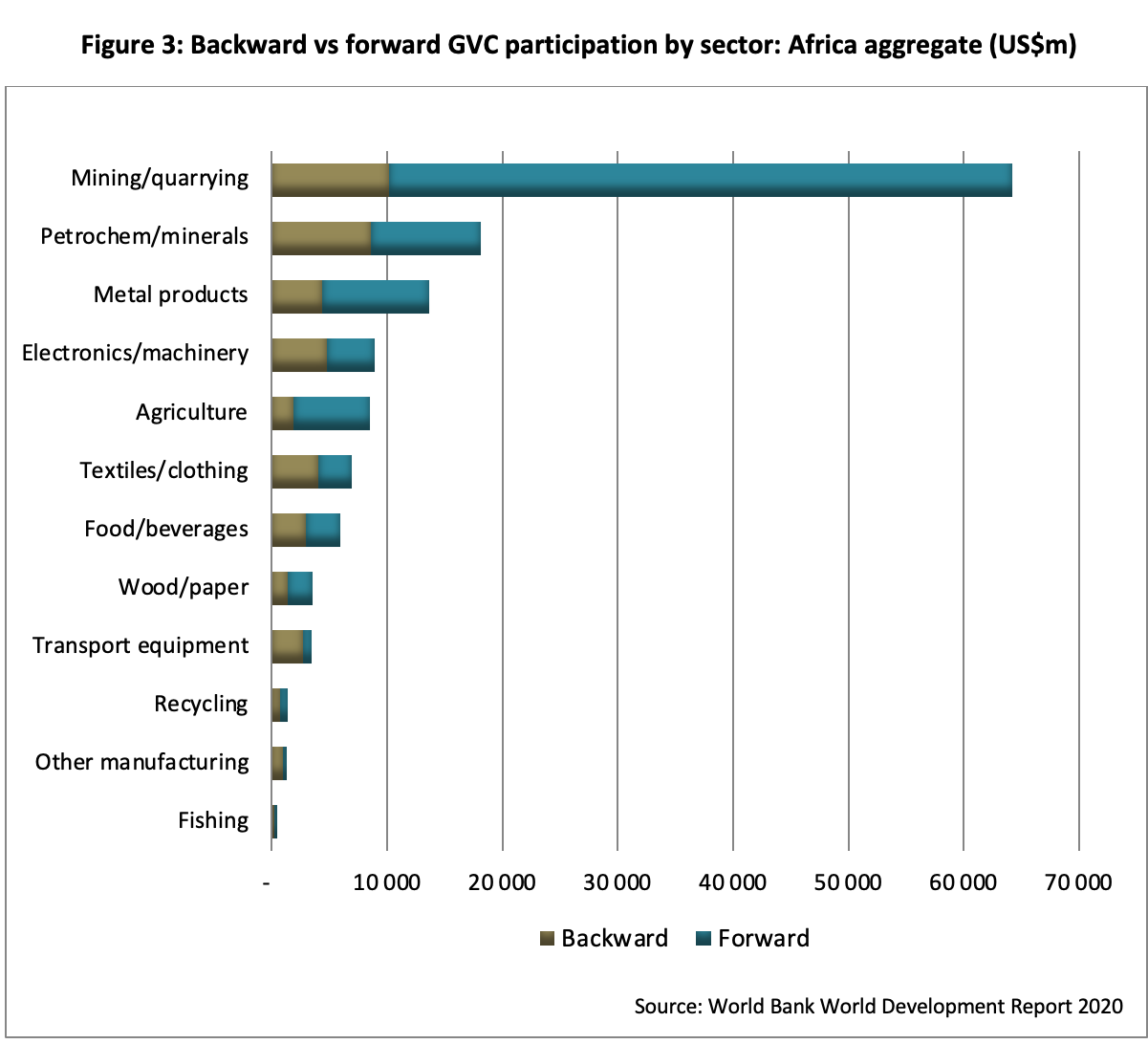

But is primary production necessarily ‘lower down the value chain ladder’? The answer is yes, evidenced by the balance between ‘forward’ value chain participation and ‘backward’ value chain participation. ‘Forward participation’ means the extent to which value is added to exported intermediate products. ‘Backward participation’ means the extent to which value is added to imported intermediate products. African countries, being overwhelmingly primary goods producers, would be expected to be far more forward than backward integrated and this is observed in the top three sectors in Figure 2.

What the figure is showing is that Africa’s top three value generation activities all contribute far greater to ‘downstream’ production than they are contributed to by ‘upstream’ production. By contrast, sectors for which backward participation clearly exceeds forward (therefore implying production is more ‘upgraded’) are textiles/clothing, transport equipment and ‘other manufacturing’. The problem seems to be that, as evidenced by the previous figure, is that these are not the type of production in which Africa has a competitive advantage globally.

This suggests that Africa will not commence climbing the value chain ladder without policy intervention. Africa’s problem relates in many ways to l'embarras des richesses (an ‘embarrassment of riches’) – a profound endowment of natural resources and therefore a way to a type of non-manufacturing industrialisation at relatively low cost[iv]. Investors will happily commit funds to the extraction of resources where these have been accurately assayed because the sale of raw materials is almost guaranteed and at prices that are relatively easy to project.

Not so investment in manufactured production. The type of capital and labour, services and business support needed to establish manufacturing industry is far more complex than that for extractive industry. Furthermore, the more sophisticated the type of production (and therefore the higher value-added), the more complex the required support system of upstream suppliers of inputs and services, especially the latter. Therefore, success creates success – silicon valley is a node of technology production that has succeeded due to its set of ‘anchor’ tech companies and large pool of skilled human resources. The more upgraded a type of production, the greater the input into it of knowledge workers and those with advanced skills.

What can African governments do to encourage upgrading and reverse the pattern of premature deindustrialisation? Recommendations for specific sectors or types of production will differ, but there are some basics that African policy makers can pay attention to. The main principle is to make an investment destination attractive to investors and to skilled personnel. Here are some steps to achieving this:

-

Strengthen democracy, transparency, accountability and public institutions.

-

Improve educational institutions and educational outcomes.

-

Pay attention to creating settlement ‘nodes’ with modern infrastructure, cheap and extensive broadband access, shopping facilities, attractive neighbourhoods and good public education services.

-

Create special industrial zones and sectors with preferential or zero tax rates/tax holidays, export subsidies (within WTO rules), subsidised labour and cheap electricity and bulk services. In other words, focus on offering investors a clear differential in unit costs versus an alternative location.

-

Ensure that labour legislation balances the rights of workers with the needs of firms to hire and fire on efficiency grounds.

-

Leverage all existing preferential access arrangements to foreign markets.

-

Avoid over-regulation and regulatory intrusion/suppression of enterprising activity.

These practices could encourage the establishment of industries that are not even necessarily connected to existing competitive industries. An African country that has recognised the value of many of these recommendations is Rwanda. One of the few African countries to shake off the effect of the global commodities slump in the mid 2010s, Rwanda has shown strong economic and export growth and has managed to attract sustained investment into a variety of sectors, including various manufacturing sectors. By following this example and actively pursuing the above objectives, African countries can reverse premature industrialisation and ensure that they are able to begin ascending the value chain ladder.

[i] https://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/global-value-chains-and-trade/

[ii] See Stuart, J. 2017. Patterns of premature industrialisation in Africa. tralac Working Paper No. S17WP03/2017. Stellenbosch: tralac.

[iii] Note that even though the data presented here is an aggregate for Africa, there are no marked deviations from these patterns when looking at the data by individual country.

[iv] C.f. the well-known economic concept known as ‘the resource curse’, see https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199599868.001.0001/acref-9780199599868-e-1574

About the Author(s)

Leave a comment

The Trade Law Centre (tralac) encourages relevant, topic-related discussion and intelligent debate. By posting comments on our website, you’ll be contributing to ongoing conversations about important trade-related issues for African countries. Before submitting your comment, please take note of our comments policy.

Read more...