Blog

Kenya-United States FTA: From AGOA towards a bilateral Free Trade Area

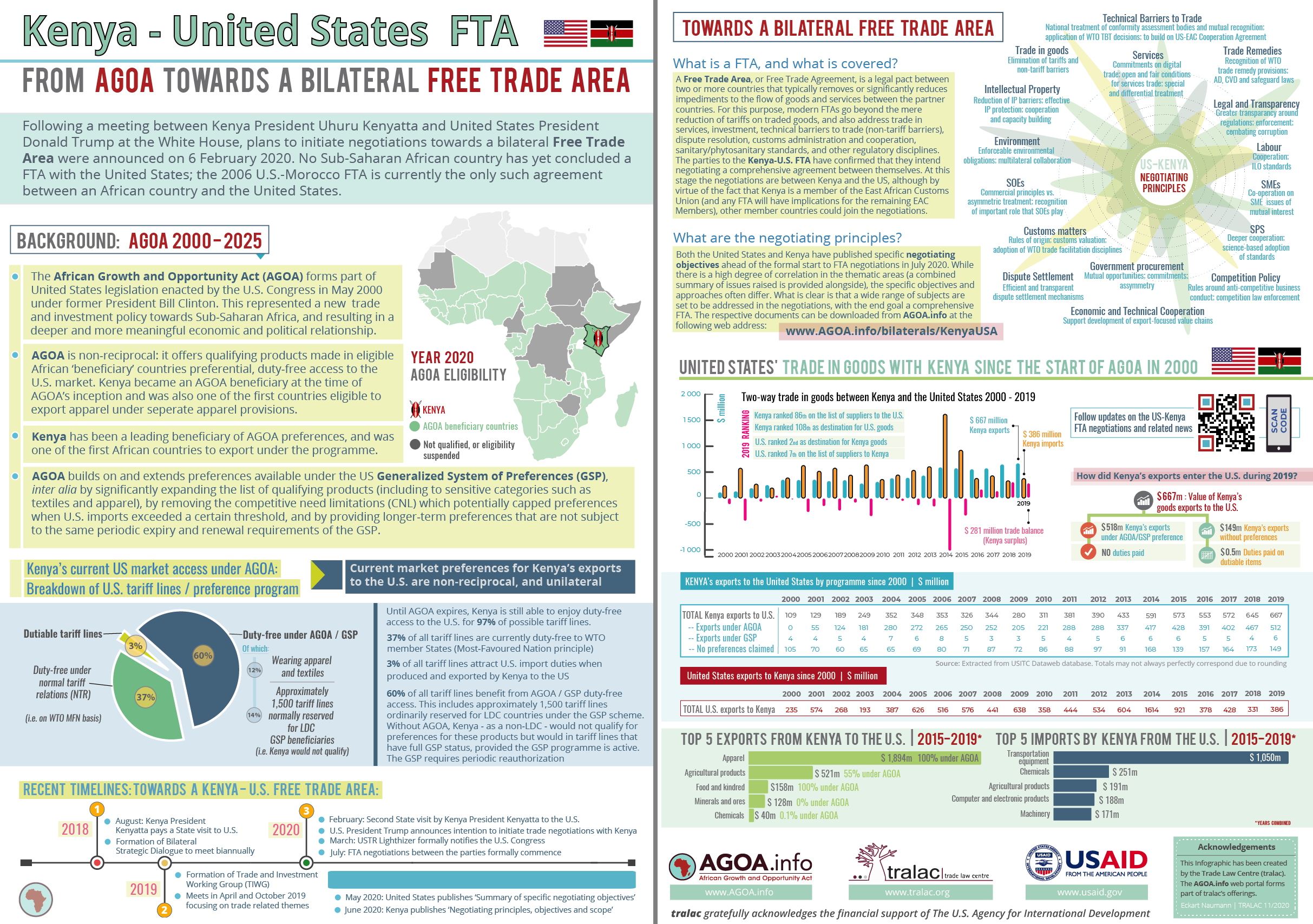

In 2018, Kenya’s president Uhuru Kenyatta paid the United States an official state visit. This lead to a Bilateral Strategic Dialogue that would meet bi-annually, followed not long after by a Trade and Investment Working Group (TIWG) with a focus on trade related themes concerning the two countries. Following a second state visit by Kenyatta to the US in early 2020, U.S. president Donald Trump announced on 6 February 2020 the U.S.’ intention to commence negotiations towards a bilateral Free Trade Area (FTA) with Kenya.

No Sub-Saharan African country currently has an FTA with the United States. Morocco is the only country on the African continent that has an FTA with the U.S. (since 2006) – under the FTA bilateral trade between the countries grew considerably with the U.S. enjoying a substantial trade in goods surplus.

An FTA between Kenya and the U.S. would be remarkable in many ways.

At this stage, and for the past two decades, the U.S. African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) has meant that no more than 3% of total tariff lines were potentially subject to import duty in the U.S. when produced in and exported by an African eligible beneficiary country, with 60% of goods receiving duty-free status under AGOA (including around 1,500 tariff lines normally available only to poorer countries with LDC status). This favourable, unilateral and non-reciprocal outcome has meant that of the $667m in goods that Kenya’s producers exported to the U.S. in 2019, $518m entered the U.S. duty-free under AGOA (or GSP). Of the remaining $149m, U.S. importers only had to pay $0.5m in import duties. But the AGOA regime is set to expire late in 2025 and there are no guarantees that GSP preferences continue uninterrupted (GSP is subject to periodic Congressional renewal legislation, which in recent times often happened long after the programme has expired, leaving traders vulnerable and uncertain).

For the U.S., Kenya would not seem a particularly important trade in goods partner relative to most others, according to the latest 2019 full year trade data: as a foreign supplier of goods to the U.S., Kenya ranked 86th, and 108th as an export destination for U.S. made goods. On the African continent, Kenya is the 7th largest supplier of goods to the U.S. in nominal terms, and – in comparison to South Africa – accounts for less than one tenth of that country’s goods exports to the U.S.

From a Kenyan perspective, the situation is however entirely different: the U.S. is Kenya’s second-most important export market and ranks 7th as a foreign supplier. As a result, Kenya enjoyed a goods trade surplus of almost $300m in its bilateral trade with the U.S. for 2019.

Aside from this bilateral trade context, there are many other considerations and issues in the geo-political context, including security, and of course the broader context of developments on the African continent. Kenya is a member of the East African Community (EAC), a customs union (CU), which ordinarily precludes individual parties from negotiating bilateral FTAs with third countries as this has implications for the other parties to the CU, which are by extension and implication either drawn into the negotiations or its outcomes, or at the very least undermines the foundations of such a pre-existing CU. Of course, this can – and may yet – be the catalyst for a broader bilateral FTA.

But Kenya is also part of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), set to finally become operational at the beginning of 2021. The AU has consistently favoured a continental agreement with major third parties such as the U.S., and Kenya going it alone seems to be contrary to this oft-expressed policy. Will these negotiations undermine the AfCFTA or ultimately galvanize greater trade policy cohesion in Africa?

Irrespective, these negotiations are set to be comprehensive and address many disciplines beyond being a simple goods-only type FTA. For example, services trade, investment, government procurement, competition policy, intellectual property, trade remedies, technical barriers to trade and many others are intended to form an integral part of such an agreement. This much is clear when analyzing the stated negotiating principles and objectives published by the U.S. and by Kenya shortly before the formal commencement of negotiations in July 2020. But what is also important and why these negotiations and outcomes matter is that they are clearly intended to serve as a blueprint for other, future negotiations with African countries. In some way, Kenya is negotiating on behalf of African countries, since a successful conclusion to these negotiations will invariably – in the same or similar shape or form – be those that will make up future bilateral FTAs between African countries and the U.S.

The attached brochure provides a broad overview – and a number of details – of the current market access arrangements that Kenya enjoys under AGOA, and relevant information and context around the planned transition (negotiations) towards a bilateral FTA, including timelines and early milestones to date, the thematic coverage and objectives of the negotiations (as published by the parties), as well as a closer view of the countries’ trade with each other.

About the Author(s)

Leave a comment

The Trade Law Centre (tralac) encourages relevant, topic-related discussion and intelligent debate. By posting comments on our website, you’ll be contributing to ongoing conversations about important trade-related issues for African countries. Before submitting your comment, please take note of our comments policy.

Read more...