Blog

South Africa’s new status as a ‘developed country’ for purposes of United States’ subsidies and countervailing duty investigations

Earlier this year, on 10 February 2020, the United States announced changes to the way in which it would conduct aspects of its trade remedy investigations, including that South Africa (and others) would now be classified as developed countries for such purposes. These changes were notified through the Federal Register.

Specifically, the US updated some of the relevant criteria and thresholds that would trigger remedial action on its part, and in particular also the conditions that could exempt countries’ exports under certain circumstances. In the process, the US updated the rules and criteria it uses for designating a country as a developed country (developed countries face stricter conditions in some trade remedy / import injury investigations); this resulted in over twenty countries – including South Africa – no longer being considered developing countries (and from now, developed) for purposes of US trade remedies legislation and specifically, countervailing duty investigations or ‘CVDs’.

In the aftermath of these developments, various local media headlines and associated articles went as far as proclaiming that South Africa had now effectively lost its access to the US market as a result of these developments, with serious repercussions. In reality, the situation is quite different. There are essentially two separate – and fundamentally unrelated – recent developments that appear to have been conflated. While the common theme indeed involves South Africa-US trade, the one relates to non-reciprocal trade preferences (the GSP eligibility / copyright legislation review), and the other to an aspect of trade remedies. This article unpacks some of these latest developments relating to the latter, and establishes to what extent the recent changes to US trade remedy laws are likely to impact South Africa.

Media headlines in February 2020

What is important to note is that the changes to the US trade remedies legislation have no direct effect on how the US treats (that) WTO Member State with respect to other laws. In other words, it does not have a direct bearing on, for example, trade preferences extended under the US Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) or indeed the AGOA program, or any other dispensation relating to developing countries.

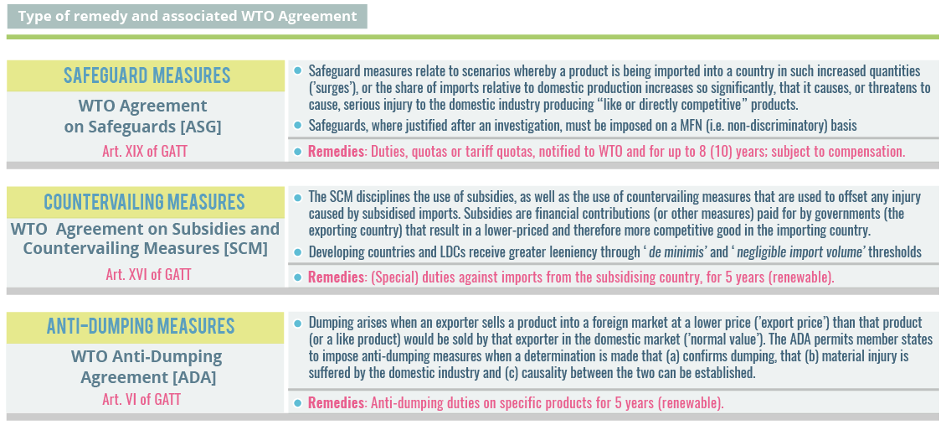

Under WTO rules, countries have the right to invoke different trade remedies pertaining to imports from other countries, under certain conditions. These WTO rules broadly relate to three main levers of trade measures, namely safeguards, anti-dumping measures and subsidies/countervailing duties. While the recent changes to US trade legislation relate primarily to subsidies and countervailing measures, for context and to better frame these developments, key aspects of each of the three types of measures are discussed briefly below.

Trade remedies 1: Safeguards

Safeguards relate to scenarios where a product is imported into a country in such increased quantities (“surge”) such that “serious injury” is caused – or threatens to be caused – to the domestic industry producing “like or directly competitive“ products. Such increased quantities can be either in nominal, absolute terms, or relative to current local production volumes (the relative measure can also entail static imports within a declining local market). Unlike anti-dumping and countervailing measures, safeguards should be applied on a MFN basis, in other words, relate non-selectively to all imports of a product rather than target specific countries. It is also not necessary to first establish unfair business or trade practices (as in the other types of trade remedies).

The WTO Agreement on Safeguards establishes the guidelines on whether serious injury is being caused (or threatened), but also stipulates the factors to be considered in determining what impacts the relevant imports are having on the domestic industry. For example, the “threat of serious injury” relates to the threat of injury that is “clearly imminent” (Art. 4); however, before any action may be taken by the importing country, an investigation based on all relevant and available facts must be conducted. On completion of an inquiry, the importing country may impose safeguards, in the form of special duties (i.e. import tariffs, and which may exceed a country’s WTO bound rates) or quantitative restrictions (i.e. quotas), or even a combination of the two (e.g. tariff quota).

Safeguards may remain in place for up to 4 years, but can potentially be extended for a combined period not exceeding 8 years. Under the special and differentiated treatment rules developing countries may however apply safeguard measures for up to 10 years. Developing and least developing countries are subject to more favourable de minimis and import volume thresholds, before action can be taken by the importing country.

Trade remedies 2: Anti-dumping

Anti-dumping is another key lever in the trio of trade defense measures. Dumping essentially arises in situations where an exporter sells products into a foreign market at a lower price than that product (or a like product) would be sold by that exporter in the domestic market. The WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement disciplines how governments may react to imports of goods that meet the “dumping” standard; in other words, the WTO regulates anti-dumping measures rather than dumping per se.

Anti-dumping measures may be imposed when a number of criteria are met, namely

-

a determination is made that confirms the presence of dumping;

-

material injury is suffered by the domestic industry of the importing country as a result of this dumping action; and

-

a causal link between the two can be established.

For each of these, a determination of the presence of dumping, of material injury, and causality between the two, detailed procedures exist in the WTO agreement. Where the presence of dumping has been established according to the relevant guidelines, remedial action would typically involve the imposition of anti-dumping duties on the product involved, usually for up to 5 years, albeit renewable following a review.

WTO Member States are required to notify the WTO of any anti-dumping action taken; 79 of the 5,833 notified anti-dumping cases represent cases taken against South African exports, with the US accounting for 19 of these (out of 715 reported cases initiated by the US). South Africa has clearly not been a big “player” in this respect.

Trade remedies 3: Subsidies and countervailing measures

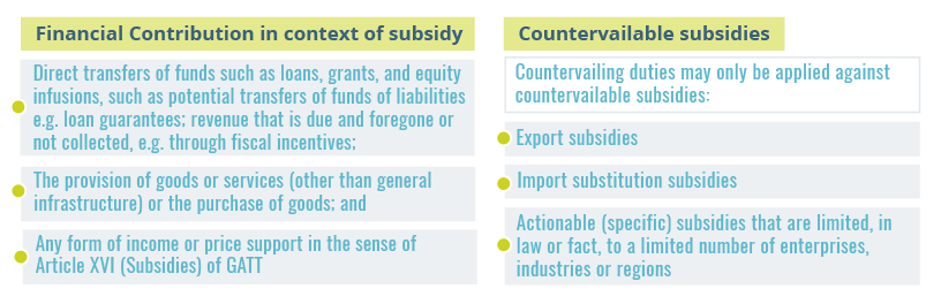

The WTO Subsidies and Countervailing Measures Agreement (SCM) disciplines the use of subsidies, along with the use of countervailing measures that are used to offset injury caused by subsidised imports. Per the SCM, countries that have not yet reached ‘developed’ country status are entitled to special (more lenient) treatment in relation to their (possibly) subsidised exports, as well as the related measures that an importing country can take against such subsidised imports.

It defines two categories of subsidies, namely prohibited subsidies and actionable subsidies (more on these later).

The intention of countervailing measures is to protect a country by countering subsidies by governments or any public body within the territory of other countries that unfairly enables their own companies to export at a lower price to another WTO Member State. There are of course different measures that can unfairly lower the price of an imported product, and result in different action (i.e. anti-dumping and countervailing); and while there are some similarities between the two, the key difference is that dumping is the action of a company while subsidies are the action of a government or government agency (incl. a state-owned company), such as the payment of subsidies or requiring firms to subsidise certain customers.

A subsidy can is one that meets all three of the following criteria,being a (1) financial contribution (2) by a government or public body, or income or price support, that (3) results in a benefit being conferred. There are two categories of subsidies – prohibited subsidies and actionable subsidies. The former is a subsidy that is dependent on one of several conditions, such as export performance (so-called export subsidies), or contingent on the use of local content (so-called local content subsidies). Actionable subsidies are those that are specific to one or more enterprises or industries or limited in its geographic application, and while such subsidies are not prohibited, they can be challenged through the multilateral system (dispute settlement) or through national action (countervailing duties).

The key aspects of the WTO SCM Agreement therefore relate to the presence of a financial contribution (giving rise to a covered subsidy), which can lead to countervailing action on the part of the country importing such subsidized goods.

This graphic below summarises these key points:

Following completion of a detailed investigation around the use and impacts of subsidized imports, WTO regulations permit a country to impose a provisional countervailing duty (if required), followed by a definitive countervailing duty, and which may be imposed for a number of years (an initial 5 years, and renewable).

US legislation

The relevant US legislation relating to trade remedies (in the broader context of the WTO/multilateral system) was enacted in December 1994 by the 103rd Congress as the ‘Uruguay Round Agreements Act’, and enacted as Public Law 103-465 (see congressional passage and legislation here). It repealed certain provisions of the US Tariff Act of 1930 relating to countervailing duties, in order to align the US’ obligations with respect to the WTO SCM Agreement imminent at the time. The US Trade Representative (USTR – equivalent to trade and industry ministry in many countries) has the delegated authority under US law to determine countries’ development status in terms of this legislation.

Title II of that legislation – ‘Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Provisions – Subtitle A: General Provisions’ as well as ‘Subtitle B: Subsidies Provisions’ sets the triggers and relevant thresholds that would activate a trade remedies investigation on the part of the US government or its institutions.

Application (and changes) in the way that the US applies CVD thresholds

How do the changes announced on 10 February change the status quo and how does this (potentially) affect South Africa?

Primarily, the US has revised a decades’ old (1998) working rule used to determine the development status of countries under the relevant countervailing duty legislation, and now considering this rule obsolete. New country designations (development status) have been decided based on these revised criteria.

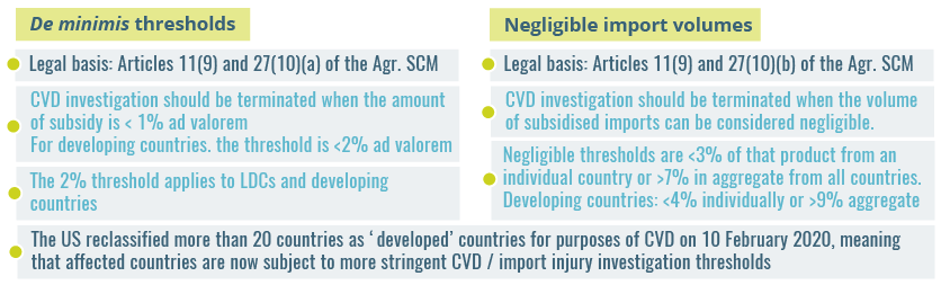

The SCM Agreement provides for special and differentiated treatment to WTO Member States that are developing and least developed; this is more lenient than the standard for developed countries. It does so in two categories:

>> De Minimis thresholds:

Under Article 11.9 of the SCM Agreement, a countervailing duty investigation relating to subsidies should be terminated when the amount of the subsidy is de minimis, defined as under 1% ad valorem, or in the case of developing countries, is less than 2% (Article 27.10(a)). The US now applies this threshold to both developing and also to least-developed countries.

>> Negligible Import Volumes:

Article 11.9 of the SCM Agreement also requires that a country terminates a countervailing duty investigation in cases where there is a negligible volume of subsidised imports entering from a country; the US considers such imports (from an individual country) as negligible if such imports account for less than 3% of total imports of a product (imported into the US), unless the aggregate volume of such imports from all countries exceeds 7% of that merchandise. For imports from developing or least-developed countries, the negligibility threshold (per US legislation) is higher, at 4% of total imports, or the aggregate volume of such imports from all countries exceeds 9% of (that) merchandise (Article 27.10(b)).

With respect to its least developed country list, the US continues to rely on the criteria of Annex VII of the SCM Agreement. While the change in its methodology has resulted in a number of countries being re-classified as ‘developed’, this has not impacted any country with LDC status. The US has updated its list with “appropriate economic, trade, and other factors“ for the country designations; this revision amends the distinction between developed countries and others, who qualify for the more lenient 2% de minimis standard.

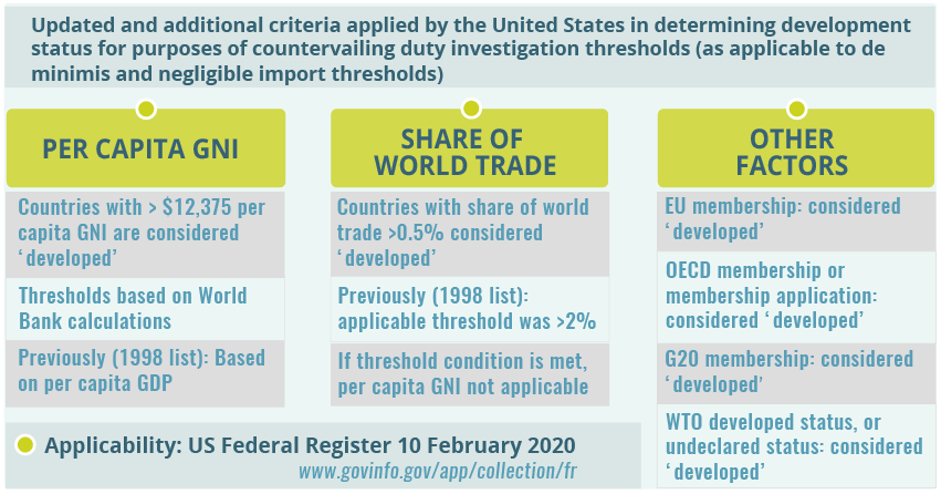

In devising new criteria for the developed country distinction, the following criteria are used: per capita GNI, the (national) share of world trade, and (a number of) “other factors” such as OECD and G20 membership.

o Per capita GNI

The US differentiates between developed countries and others based on per capita GNI (gross domestic income), a change from per capita GDP (gross domestic product) previously. The World Bank considers countries with a GNI exceeding $12,375 (up from $12,055 in 2018) based on the Atlas method as high income countries. Based on this methodology, for example, Argentina is now no longer classified as a high income country, but met the US criteria in other ways under the new rules (see section on G20 membership below, along with reference to South Africa).

o Share of World Trade

A country’s share of world trade is a further criterion used in the revised list, having been used previously in the ‘1998’ list albeit on a far more lenient basis. Previously, countries whose trade exceeded 2% of world trade were considered as ineligible for the higher (2%) de minimis threshold, but in the revised criteria, the US has reduced this threshold by three quarters to 0.5% of world trade. As a consequence, a number of countries with low per capita GNI (in terms of the first criteria) yet with a share of world trade in excess of 0.5% now become classified as developed countries for purposes of trade remedy legislation and are no longer subject to the higher 2% de minimis standard. The countries impacted are Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam.

o Other Factors

Apart from the per capita GNI and world trade share criteria, the US has also considered a range of additional criteria in the revised ‘country list’ (the USTR is empowered to consider other factors in terms of its legislation...”In determining whether a country is a developing country under subparagraph (A), the Trade Representative shall consider such economic, trade, and other factors which the Trade Representative considers appropriate…” .With this in mind, the USTR has considered or updated the following factors:

(i) EU Membership:

The US treats the EU as a single country for purposes of its countervailing duty practices, arguing that membership of the body is indicative of relatively high levels of development and its own track record of trade remedy investigations against the EU as a collective. Arguing that it “would be anomalous to treat an individual EU Member as eligible for that [higher de minimis threshold] standard...” As a result, Bulgaria and Romania are now classified as ‘developed’ despite being below the GNI per capita threshold for that classification criteria.

(ii) OECD Membership:

This relates to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), whose stated goal is to “to shape policies that foster prosperity, equality, opportunity and well-being for all“. The USTR goes on to state that “the OECD consistently has been viewed as, and acts itself in the capacity of, the principal organization of developed economies worldwide” and consequently (the US) considers a country’s membership, including the act of applying to join, as a de facto self-declaration of a country’s development status. In 1998, only membership rather than the act of applying to join was considered in US criteria. Consequently, Columbia and Costa Rica are now both ineligible for the 2% de minimis rule despite their respective per capita GNI falling short of the World Bank ‘developed country’ threshold.

(iii) G20 Membership:

The G20 brings together governments and central bank governors representing nineteen individual countries, plus the European Union, and therefore represents a mix of the world’s largest advanced and emerging countries, 85% of the world’s GDP and 75% of its global trade. The individual member countries are Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Germany, France, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, the Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, the UK and the US. Given the G20’s establishment in 1999 it could not be considered for the 1998 list, the US considers this collaborative group influential enough – and representative through the “collective economic weight of its membership” – to consider its members to be developed countries and thus also ineligible for the 2% de minimis standard. This is irrespective of a country’s actual development indicators, per capita GNI and so forth. As a result, Africa’s sole G20 member – South Africa – is no longer considered a developing country for purposes of US countervailing duty investigations. Other G20 countries in a similar situation are Argentina, Brazil, India and Indonesia.

(iv) Development status under WTO disciplines:

The US also looked at the self-declared (or indeed un-declared) development status of WTO Member Countries (with respect to their WTO membership) and now considers countries that have self-declared themselves as ‘developed’ countries, or who have omitted declaring their status in their WTO membership process, as developed countries for purposes of CVD purposes. WTO rules do not define what constitutes a developed or developing country; developing countries however obtain additional rights relative to developed countries, for example through longer transition periods in relation to tariff liberalisation measures, etc. The US now considers Albania, Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Ukraine as developed countries for purposes of the de minimis rule.

United States CVD procedures, and how does this link to the changes in February 2020?

The US Tariff Act of 1930, and specifically Title VII, provides some of the legal guidance on the way that the US conducts countervailing duty (and anti-dumping) investigations. US industries may petition the US government for relief from imports that are sold at below fair value (dumping / anti-dumping) or whose price is impacted by subsidies paid by foreign governments (subsidies / CVDs). The WTO requires that a country has an investigating authority; in the US, the institutions dealing with ‘injury investigations’ are the US Department of Commerce and the US International Trade Commission (USITC).

The Commerce department is responsible for the initial determination of whether there is dumping or subsidisation, and the amount of the subsidy (or dumping margin). The USITC then assesses the presence of material injury (or threat thereof).

Once a petition has been received, a preliminary investigation is undertaken; during the preliminary investigation, the USITC makes a determination based on two factors: (1) a reasonable indication of material injury (or threat thereof) and (2) whether “the establishment of an industry is materially retarded” due to imports under investigation being dumped or subsidised and thus sold at a lower price.

Investigations continue based on evidence pointing to subsidised imports; however if import volumes fall below the de minimis thresholds, then an investigation is terminated. This is essentially the “backstop” that has now been changed, as of 10 February, with South Africa and more than twenty other countries no longer benefiting from the higher and more lenient thresholds, since for purposes of these subsidy and countervailing duty investigations, they are now considered developed countries.

A dumping (AD investigation) or CVD (subsidy investigation) order is issued by the Commerce Secretary in cases of a positive/affirmative finding, or terminated on the basis of a negative finding, and when negligible import volume thresholds come into play.

Where does South Africa feature in US import injury investigations?

South Africa has been the subject of approximately twenty ‘import injury’ investigations (anti-dumping and countervailing duty) by the US since 2003. These, along with the related remedial action, are listed by the USITC in its register of investigations (or this link – already with ‘South Africa’ filter applied). While most of these investigations feature two countries or more (including South Africa), a small number relate to imports from South Africa only.

However, almost all investigations relate to dumping rather than subsidised imports , and most pertain to products such as steel, manganese, ferro-vanadium, aluminium, and most recently, acetone. One long-standing investigation that does involve subsidy investigations against South Africa and brings into play countervailing duties is ‘stainless steel plate in coils’ which under further sunset reviews (see for example here and here) led to a continuation of the countervailing duty rates (of 3.95%) against imports from South Africa.

No record was found showing any investigation against (allegedly) subsidised imports from South Africa having been terminated on the grounds of any de minimis or import volume thresholds being breached, which may be reflective of low risk exposure for South African exports to the US following the revised CVD rules recently implemented. South Africa is not generally a candidate for CVD investigations against its exports, and according to a source [Perscom. Dr Gustav Brink 22 April 2020] has not had such measures imposed against it in the last 18 years.

United States imports from South Africa: are any products at risk?

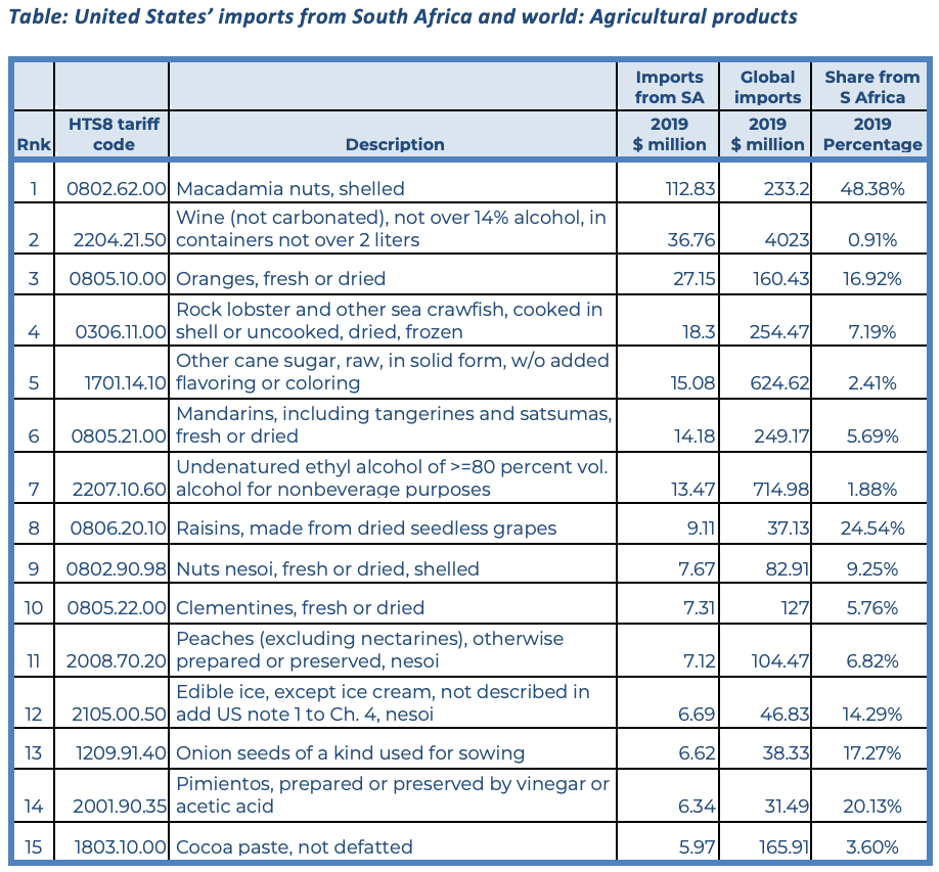

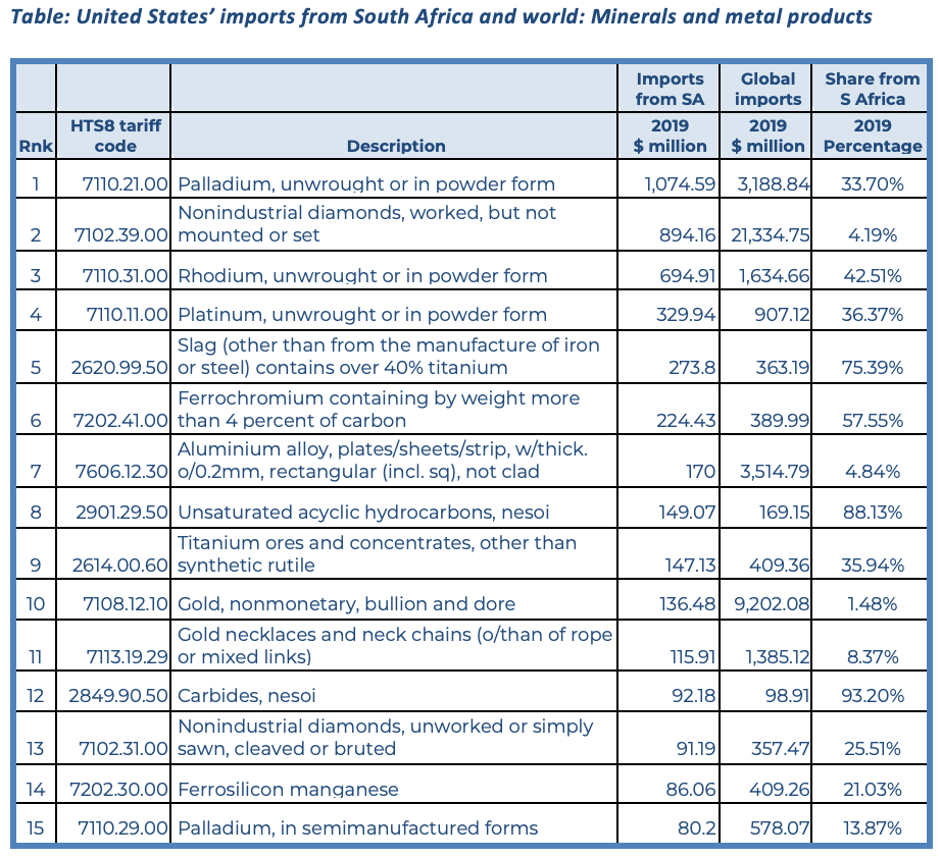

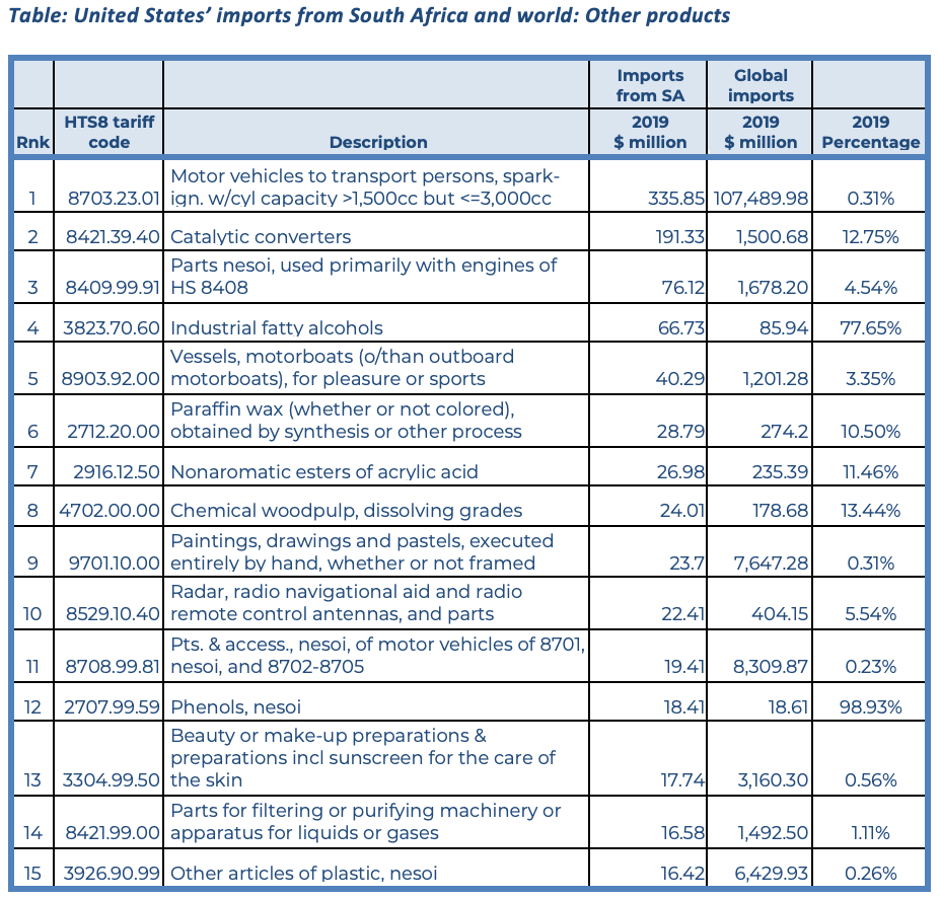

An analysis of the United States’ imports (full year 2019) from South Africa indicates that the (import market) share of South African-made goods with respect to certain tariff lines into the US, is substantial. Many of these significantly exceed the 4% ‘Negligible Import Volumes’ threshold that could potentially come into play (now revised downward to 3% for South Africa as a ‘developed’ country for purposes of CVDs).

Different factors are considered when launching and investigating subsidised imports, the damage to local equivalent products, and so forth. There is also no set standard for which disaggregated level of tariff classification is used, for different reasons, including presumably the fact that industrial activity and production uses different classification codes which do not necessarily overlap. Indeed, domestic ‘like’ products that face injury in the US or any other domestic market could also be identified based on the raw materials used, the physical characteristics, substitutability, production processes and so on. But for the purposes of this illustration, the following tables show US import data at the HTS8-digit ‘sub-heading’ level, similar to what has been used in various US anti-dumping investigations and findings.

The trade data is broadly divided into ‘agricultural’ products (from HS chapters 1-25), ‘minerals and metals’, and others (i.e. manufactured and industrial goods etc.), and shows leading US product imports from South Africa for each category. Imports from South Africa are compared to the US’ global imports in the same products. The percentage value is a simple share of US imports sourced from South Africa, as a proportion of total US imports (global) for that specific tariff line (i.e. the HTS8 sub-heading).

The trade data shows that South Africa accounts for a significant share of US imports in a number of agricultural, resource and industrial tariff subheadings. In agriculture, leading product lines (macadamias, raisins, onion seeds, pimientos, and oranges) show high import concentrations in the US, with many over 15% of total US imports in 2019. Only two of the top 15 agricultural tariff lines are below the 3% “threshold” (the revised ‘negligible import volumes’ exemption threshold), being wine, ‘other’ cane sugar and undenatured ethyl alcohol.

For mineral and metal products, the situation is similar, if not more amplified. While those in the table are obviously only a small number of the total number of possible tariff lines, they do provide some indication of import concentration relating to products sourced from South Africa. All but one of these tariff lines (South Africa’s top 15 exports to the US in this broad category) were below the 3% threshold in 2019.

The other, mainly industrial products, also show a number of significant import concentrations. For example, industrial fatty alcohols are one of South Africa’s key exports to the US and account for almost 80% of total US imports globally. For phenols not elsewhere specified or included, South Africa’s share of the US import market is much higher at 99%.

Concluding remarks

The changes to the way that the US will conduct CVD investigations, and the revised classification criteria that resulted in South Africa and more than twenty other countries losing their ‘developing’ country status for purposes of these investigations, caused significant concern in South Africa and elsewhere. Some of the reaction by sections of the local media was particularly strong, if not always accurate or indeed correct (some resulting from a clear conflation of entirely separate ongoing developments, i.e. the separate review of South Africa’s GSP eligibility status).

South Africa’s trade ministry, the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (dtic), framed its reaction to these US trade remedy developments within the broader context of developments at the WTO, where the US has for some time taken issue with some aspects of the application of the principle of special and differentiated treatment (also see White House memorandum here), especially where this was linked to some countries that (it felt) should in reality not be classified as developing or least developed countries (and thereby shield themselves from making greater commitments, or obtain benefits and concessions, reserved for perhaps more vulnerable countries). A particular sorepoint revolves around the self-declared (or indeed un-declared) development status in the WTO context, impacting trade-related negotiations and concessions. The decision by the US to tighten its own trade remedies rules must also be seen in this context. It is worth noting that South Africa negotiated its GATT tariff commitments (and others) as a self-declared ‘developed’ country, and made concessions that some, including the DTI, consider as having had damaging impacts on the country’s industry and indeed broader economy and unemployment levels.

What is also clear is that South Africa is essentially caught up in much broader global political-economic developments, in this respect perhaps also the US’ somewhat fraught relationship with the WTO and the multilateral system in general, and related to this, the “imbalance” in global trade (whether perceived, actual, justified or not justified) with respect to the US and its main trade partners, including China and others.

With South Africa now considered a ‘developed’ country by the US for purposes of CVD investigations, a review of the history of that country’s CVD and anti-dumping investigations involving South Africa revealed that almost all of these related to anti-dumping (and thus penalises primarily certain companies), rather than CVD investigations based on the payment by the South African government of illegal (and injurious to local operators in the US market) subsidies. This would indicate that the issue is clearly not a widespread and broadly prevailing one, exposing future exports to excessive new risks. The DTI response implied that South Africa does not pay subsidies, certainly not in a WTO-incompatible manner, and therefore the risk exposure from its perspective should be limited. The general record of (alack of) CVD investigations against South Africa supports this.

Drawing on the trade data (US imports from South Africa versus its global imports), it is clear that the US sources large percentage shares of its global imports of a number of products from South Africa, and based on the trade data alone (and with reference to the negligible import volume exemption / CVD investigations), the change from 4% (developing countries) to the slightly more restrictive 3% threshold (developed country classification) would seem to be largely inconsequential from a South African perspective. Many of South Africa’s exports to the US are at much higher import concentrations already.

It is probably fair to conclude then that any issue of illegal subsidies as it pertains to SA-US trade is in any case not a significant worry, or one that is of much current relevance. Going forward, could economic support measures by the South African government, in response to the global COVID-19 pandemic, have possible future consequences and impacts on how South Africa’s exports are viewed by the US? At least for now, there appears little need for concern about negative impacts for South Africa’s exports to the US following the revised US CVD rules.

Selected references and sources:

Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute. [Online]

G20. Membership [Online]

OECD. [Online]

The White House. Memorandum on reforming developing country status [Online]

The World Bank. Income level classifications [Online]

USITC. Import injury investigations register [Online]

US Department of Commerce, Countervailing Division. [Online]

United States. Federal Register (2020). [Online]

United States Congress. CVD Legislation [Online]

United States International Trade Commission (USITC). [Online]

WTO. Communication from the United States [Online]

WTO. Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures [Online]

WTO. Trade Topics: Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures [Online]

WTO Anti-dumping initiations: Reporting member vs exporting country 01/01/1995 - 30/06/2019 [Online]

WTO. Technical information on safeguard measures. [Online]

About the Author(s)

Leave a comment

The Trade Law Centre (tralac) encourages relevant, topic-related discussion and intelligent debate. By posting comments on our website, you’ll be contributing to ongoing conversations about important trade-related issues for African countries. Before submitting your comment, please take note of our comments policy.

Read more...