Blog

Coronavirus, food supply and demand constraints: panic-buying and logistics

As South Africa’s President announced various social distancing measures as part of a Covid-19 State of Emergency to curb the spread of the virus, numerous concerns about access to imports led people flocking to retailers to panic-buy and stock-up on various food and non-food items. This has led to various questions being raised about how secure South Africa’s food supply is in the time of the current pandemic. Initial concerns were related to the potential impact of the strict lockdown measures put in place in China but have subsequently increased as more countries implement similar measures.

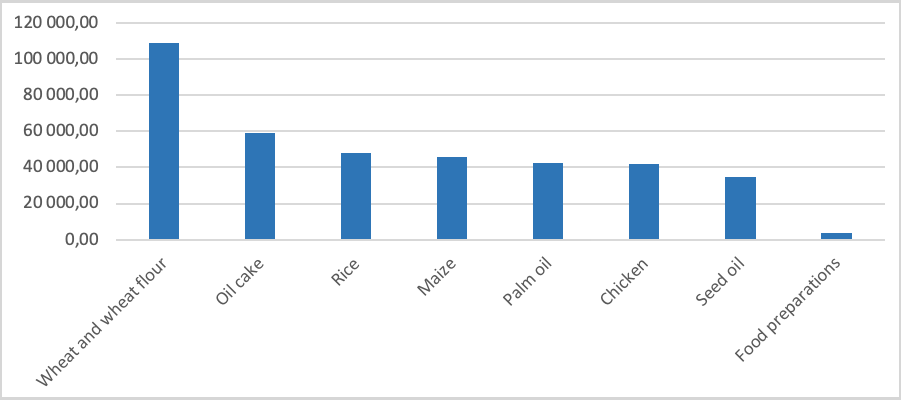

In terms of food products, South Africa hardly sources any food items from China although some inputs into the production process are sourced from China. In 2019 only 0.4% of South Africa’s total world imports were agricultural goods (valued at US$6 billion) which were mainly imported from Argentina, Thailand and Eswatini. The main import products include rice, wheat, palm oil and sugar. According to the data from the South African Revenue Services (SARS) for imports for January 2020 South Africa imported significant volumes of wheat and wheat flour (109 000 tons), oil cake (59 000 tons), rice (48 000 tons) and maize (46 000 tons) in January.

Figure 1: South Africa’s imports of designated food items in January 2020 (actual tons)

Source: SARS (2020)

Furthermore, the latest demand and supply estimates for grains and oilseeds (by the National Agricultural Marketing Council (NAMC)) show that the domestic supply for the 2020/2021 season of white maize, yellow maize, sorghum, wheat, sunflower seeds and soybeans to be 8.3 million tons, 5.9 million tons, 132 310 tons, 1.5 million tons, 731 210 tons and 1.2 million tons respectively. Also, there are good projections for South Africa’s fruit and vegetable growing seasons. In terms of meat production and imports, the main import product is poultry; however, the South African poultry industry has consistently highlighted their ability to fulfill domestic demand with domestic supply if afforded the chance without competition from uncompetitively priced imports.

What does the data mean? Basically, South Africa does produce a significant amount of basic and raw food items domestically; however, there are some staples which South Africa either does not produce or produces insufficient quantities of and some of the measures taken to curb the spread of the virus can lead to supply disruptions.

Disruptions of imports can lead to supply issues for certain products including rice, wheat, fertilizer, seeds, feed and products used in food preparations. These supply-side challenges can arise due to a number of factors: some countries have temporarily banned the export of basic food items like rice and wheat; as countries increasingly restrict the movement of persons allowing only for the production of essential items the availability of certain products will be affected; staff and worker shortages can lead to a slow down in productions and logistic issues can lead to disruptions in the supply chain. Restricting movement across borders leads to delays in the transport of goods, but also an overall slowdown in production and trade has resulted in a shortage of reefer containers which are necessary for the maritime transportation of goods. Delays in ports due to entry restrictions, staff shortages and new sanitation requirements can slow down the supply chain. Furthermore, seasonality along with disruptions in imports will lead to a change in the range of food items and the variety of available products.

However, limiting the impact of the virus and consequent movement restrictions on the domestic supply chain is vital to ensure the flow of basic foods through South Africa. It is this supply chain which gets disrupted with panic-buying, roadblocks and the requirement that those rendering essential services need to be permitted to conduct their business. Although the extensive measures taken to limit the spread of the virus have been commended by most, the implementation of these measures should not give rise to non-tariff barriers to trade leading to artificial food shortages – the unnecessary limitation of the movement of farmworkers, trucks and truck drivers, factory workers and logistics.. and warehousing staff will have an impact on the flow and availability of food items which can lead to a spiral of events – artificial shortages, panic about food shortages, panic-buying and further artificial shortages.

About the Author(s)

Leave a comment

The Trade Law Centre (tralac) encourages relevant, topic-related discussion and intelligent debate. By posting comments on our website, you’ll be contributing to ongoing conversations about important trade-related issues for African countries. Before submitting your comment, please take note of our comments policy.

Read more...