News

Global economy stuck in low-growth trap: Policymakers need to act to keep promises, OECD says in latest Economic Outlook

The global economy is stuck in a low-growth trap that will require more coordinated and comprehensive use of fiscal, monetary and structural policies to move to a higher growth path and ensure that promises are kept to both young and old, according to the OECD’s latest Global Economic Outlook.

“Growth is flat in the advanced economies and has slowed in many of the emerging economies that have been the global locomotive since the crisis,” OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría said while launching the Outlook during the Organisation’s annual Ministerial Council Meeting and Forum in Paris. “Slower productivity growth and rising inequality pose further challenges. Comprehensive policy action is urgently needed to ensure that we get off this disappointing growth path and propel our economies to levels that will safeguard living standards for all,” Mr Gurría said.

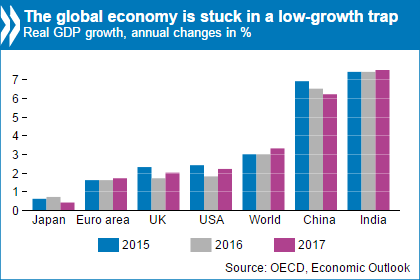

Weak trade growth, sluggish investment, subdued wages and slower activity in key emerging markets will all contribute to modest global GDP growth of 3% in 2016, essentially the same level as in 2015, according to the Outlook. Global recovery is expected to improve only to 3.3% in 2017.

Among the major advanced economies, the moderate recovery will continue in the United States, which is projected to grow by 1.8% in 2016 and 2.2% in 2017. The euro area will improve slowly, with growth of 1.6% in 2016 and 1.7% in 2017. In Japan, growth is projected at 0.7% in 2016 and 0.4% in 2017. The 34-country OECD area is projected to grow by 1.8% in 2016 and 2.1% in 2017, according to the Outlook.

With rebalancing continuing in China, growth is expected to continue to drift lower to 6.5% in 2016 and 6.2% in 2017, supported by demand stimulus. India’s growth rates are expected to hover near 7.5% this year and next, but many emerging market economies continue to lose momentum. The deep recessions in Russia and Brazil will persist, with Brazil expected to contract by 4.3% in 2016 and 1.7% in 2017.

The Outlook draws attention to a number of downside risks. Most immediately, a United Kingdom vote to leave the European Union would trigger negative economic effects on the UK, other European countries and the rest of the world. Brexit would lead to economic uncertainty and hinder trade growth, with global effects being even stronger if the British withdrawal from the EU triggers volatility in financial markets. By 2030, post-Brexit UK GDP could be over 5% lower than if the country remained in the European Union.

“If we don’t take action to boost productivity and potential growth, both younger and older generations will be worse off,” said OECD Chief Economist Catherine L Mann. “The longer the global economy remains in this low-growth trap, the harder it will be for governments to meet fundamental promises. The consequences of policy inaction will be low career prospects for today’s youth, who have suffered so much already from the crisis, and lower retirement income for future pensioners.”

The OECD highlights a series of policy requirements, including more comprehensive use of fiscal policy and revived structural reforms to break out of the low-growth trap.

The Outlook argues that reliance on monetary policy alone cannot deliver satisfactory growth and inflation. Additional monetary policy easing could now prove to be less effective than in the past, and even counterproductive in some circumstances.

Many countries have room for fiscal policies to strengthen activity via public investment, especially as low long-term interest rates have effectively increased fiscal space. While almost all countries have scope to reallocate public spending towards more growth-friendly projects, collective action across economies to raise public investment in projects with a high growth impact would boost demand and improve fiscal sustainability.

Given the weak global economy and the backdrop of rising income inequality in many countries, more ambitious structural reforms – in particular targeting services sectors – can boost demand in the short-term and promote long-term improvements in employment, productivity growth and inclusiveness, the OECD said.

Policymakers: Act now to break out of the low-growth trap and deliver on our promises

Editorial by Catherine L. Mann, OECD Chief Economist, 1 June 2016

Policymaking is at an important juncture. Without comprehensive, coherent and collective action, disappointing and sluggish growth will persist, making it increasingly difficult to make good on promises to current and future generations.

Global growth has languished over the past eight years as OECD economies have struggled to average only 2 per cent per year, and emerging markets have slowed, with some falling into deep recession. In this Economic Outlook the global economy is set to grow by only 3.3 per cent in 2017. Continuing the cycle of forecast optimism followed by disappointment, global growth has been marked down, by some 0.3 per cent, for 2016 and 2017 since the November Outlook.

The prolonged period of low growth has precipitated a self-fulfilling low-growth trap. Business has little incentive to invest given insufficient demand at home and in the global economy, continued uncertainties, and a slowed pace of structural reform. In addition, although the unemployment rate in the OECD is projected to fall to 6.2 per cent by 2017, 39 million people will still be out of work, almost 6.5 million more than before the crisis. Muted wage gains and rising inequality depress consumption growth. Global trade growth, at less than 3 per cent on average over the projection period, is well below historical rates, as value-chain intensive and commodity-based trade are being held back by factors ranging from spreading protectionism to China rebalancing toward consumption-oriented growth.

Negative feedback-loops are at work. Lack of investment erodes the capital stock and limits the diffusion of innovations. Skill mismatches and forbearance by banks capture labour and capital in low productivity firms. Sluggish trade prospects slow knowledge transfer. These malignant forces slow down productivity growth, constraining potential output, investment, and trade. In per capita terms, the potential of the OECD economies to grow has halved from just below 2 per cent 20 years ago to less than one per cent per year, and the drop across emerging markets is similarly dramatic. The sobering fact is that it will take 70 years, instead of 35, to double living standards.

The low-growth trap is not ordained by demographics or globalization and technological change. Rather, these can be harnessed to achieve a different global growth path – one with higher employment, faster wage growth, more robust consumption with greater equity. The high-growth path would reinvigorate trade and more innovation would diffuse from the frontier firms as businesses respond to economic signals and invest in new products, processes, and workplaces.

What configuration of fiscal, monetary, and structural policies can propel economies from the low-growth trap to the high-growth path, safeguarding living standards for both young and older generations?

Monetary policy has been the main tool, used alone for too long. In trying to revive economic growth alone, with little help from fiscal or structural policies, the balance of benefits-to-risks is tipping. Financial markets have been signalling that monetary policy is overburdened. Pricing of risks to maturity, credit, and liquidity are so sensitized that small changes in investor attitude have generated volatility spikes, such as in late 2015 and again in early 2016.

Fiscal policy must be deployed more extensively, and can take advantage of the environment created by monetary policy. Governments today can lock in very low interest rates for very long maturities to effectively open up fiscal space. Prioritized and highquality spending generates the capacity to repay the obligations in the longer term while also supporting growth today. Countries have different needs and initial situations, but OECD research points to the kind of projects and activities that have high multipliers, including both hard infrastructure (such as digital, energy, and transport) and soft infrastructure (including early education and innovation). The right choices will catalyse business investment, which, as the Outlook of a year ago argued, is ultimately the key to propelling the economy from the low-growth trap to the high-growth path.

The high-growth path cannot be achieved without structural policies that enhance market competition, innovation, and dynamism; increase labour market skills and mobility; and strengthen financial market stability and functioning. As outlined in the special chapter in this Outlook, the OECD’s Going for Growth and the comprehensive Productivity for Inclusive Growth Nexus Report of the OECD Ministerial Summit, there is a coherent policy set for each country based on its own characteristics and objectives that can raise productivity, growth and equity.

The need is urgent. The longer the global economy remains in the low-growth trap, the more difficult it will be to break the negative feedback loops, revive market forces, and boost economies to the high-growth path. As it is, a negative shock could tip the world back into another deep downturn. Even now, the consequences of policy inaction have damaged prospects for today’s youth with 15 per cent of them in the OECD not in education, employment, or training; have drastically reduced the retirement incomes people are likely to get from pension funds compared to those who retired in 2000; and have left us on a carbon path that will leave us vulnerable to climatic disruption.

Citizens of the global economy deserve a better outcome. If policymakers act, they can deliver to raise the future path of output – which is the wherewithal for economies to make good on promises – to create jobs and develop career paths for young people, to pay for health and pension commitments to old people, to ensure that investors receive adequate returns on their assets, and to safeguard the planet.